Many books take familiar themes and tackle them in different ways, but here at Polymath, we’ve never encountered anything quite like ‘The Carnival Of Hermit The Bog’, which is currently available on Amazon Kindle. We speak to the authors, Tom Flint and Colin Williams, to find out how they managed to create something so unique, funny and occasionally mind blowing.

PP: How did you come up with the idea to write the book?

Tom: When we were about 13 or 14, we set up an imaginary business in the garage roof space at my parents’ house, using a camping table as a desk and an old Bakelite telephone as our means of communication with pretend customers. People would call in and give us jobs and we would get to work on them. Inevitably these jobs were ones we wanted to do at that very moment! So on one occasion Colin took a call asking for a story to be written and he came up with a thrilling adventure called The Cavern. His effort was absolutely terrible and when we read it back we were in fits of laughter. We inserted jokes and came up with the idea to write more stories that had the trappings of serious adventures but with extremely funny disastrous events happening throughout. In effect, we subjected the charters to ironic tragedies, which amused us no end. The stories were still very basic and crudely written, but it was a start. Eventually we incorporated them into a longer story and the whole thing evolved from there.

Colin: I wouldn’t say that it was as structured as coming up with the idea to write a book. It was something that just happened. It was one of those moments where you write something down and that sparks something in the other person. That becomes a virtuous circle.

PP: That’s a long time ago! How long did it take to write?

Tom: It was a long time ago. It took many years to write but we certainly weren’t working on it all the time. Every so often we’d have a go at making it better and incorporating more ideas and situations.

Colin: It must have taken about 25 to 30 years! Sometimes you need a bit of time for things to settle in your mind and then you come back to it!

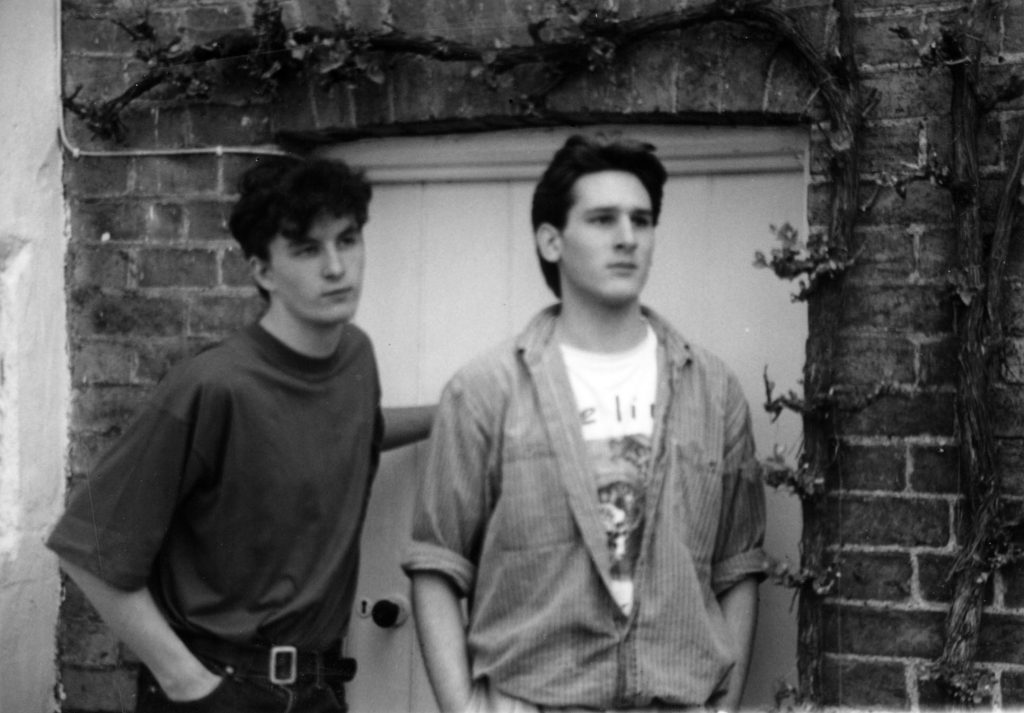

The writers, pictured here during the early days…

PP: Can you explain what the book is about?

That’s tricky, but obviously a vital question! There is a central character called Jim Leighton. He was there at the start but was first named Jim McNeil. That somehow changed to Jim Leighton, possibly because there used to be a Scottish goalkeeper with that name when we began writing and it made its way into our collative subconscious.

At first he was just a kind of scruffy foolish character. Possibly a little like Stan Laurel’s persona mixed with Shaggy from Scooby Do, but at some point we made him into a detective and a bit of Inspector Clouseau crept into the mix. So we gave him an authority that the likes of Shaggy and Laurel never had. He’s very much an anti-hero though.

Essentially Jim creates chaos wherever he goes in a Frank Spencer sort of way, and this creates many enemies who try to kill him. As the story progresses, he goes on a massive adventure that involves the universe. I don’t want to give too much away, but the story is pretty ambitious. We get deeply philosophical and incorporate some rather big ideas, but keep everything ticking over with a nice mix of sophisticated and puerile humour.

Colin: I think the book is about the journey through life. It is about why we are here, and tries to explain what the point of it all is. And it’s about the struggles that Leighton has with those big questions, while not actually really realising he is struggling with them!

PP: Tell me about the early drafts, how were they done?

Colin: We started writing in a lined A4 notepad which we swapped between us. Writing it all down the old fashion way was good at first but eventually the bits of paper got so confused with comments and things crossed out that we decided it would be good to put it on computer. I can remember sitting down and spending many an evening typing it all into my old BBC Micro computer. It probably wasn’t the best place to put it because it wasn’t exactly a location that was future proof. So later on I can remember typing it in again into a PC, and since then it has wended its way from one place to another in the digital universe and been worked on in several countries at least.

PP: How did that work?

Colin: Sometimes one of us had control of it, as it were, and was the editor at that moment and would take input from both of us. Then another time the other one of us would take over the role of editor. That way strange things would creep in. For example, you might change the bits that the other person had written and then that would spark off ideas in the other person when they read it. And that would give a whole new direction to the story.

Tom: Early on Colin was the one with access to a computer and I had no typing skills, so he tended to act as editor. Later on I got a job writing for magazines and my editing and typing skills got quite good, so I pushed it forward a little more at that stage. Eventually we were living in different parts of the country so we’d have brainstorming sessions every so often where we’d get together, decide what needed to be done, and assign each other with the task of writing the sections we’d agreed upon. Once these were done, one of us would become editor and incorporate them into the master text. As the book got longer the editing process became more demanding, so there were periods of time where the manuscript sat there doing nothing until we hit it again and moved it along a bit.

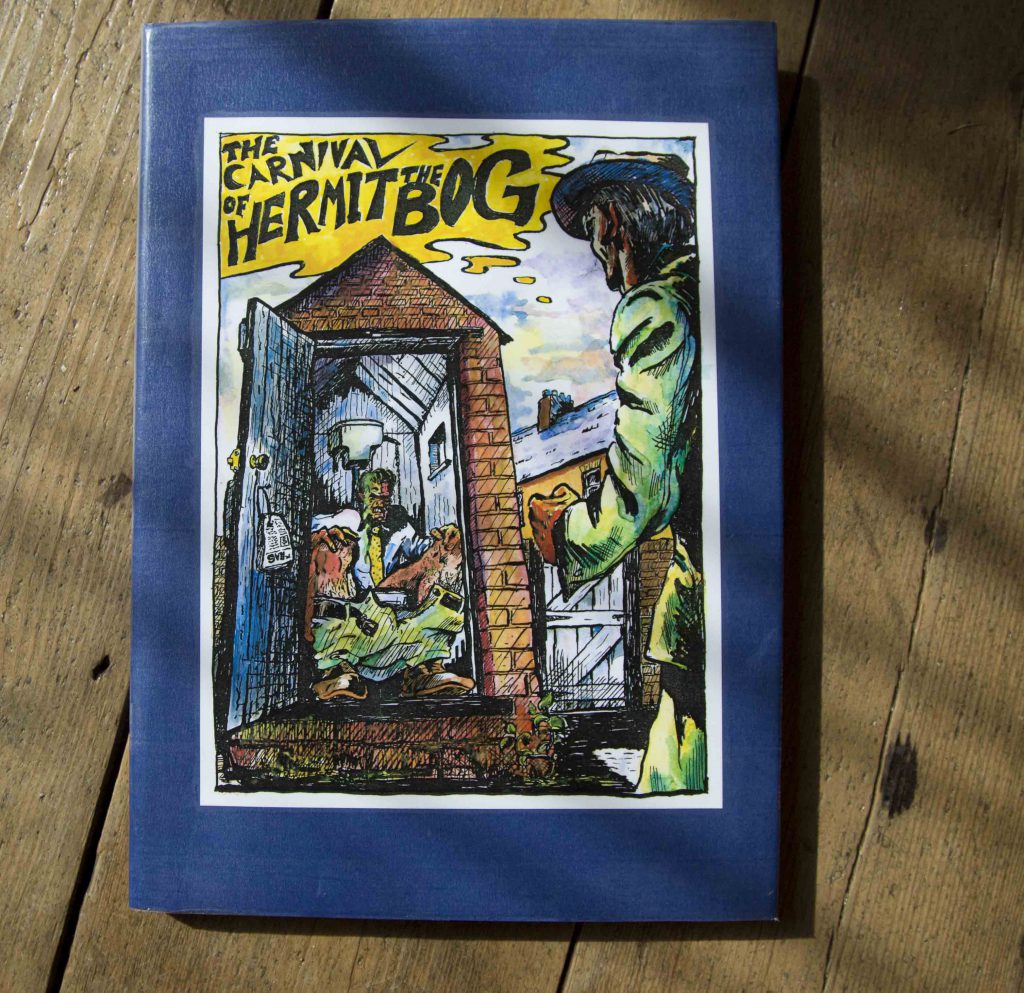

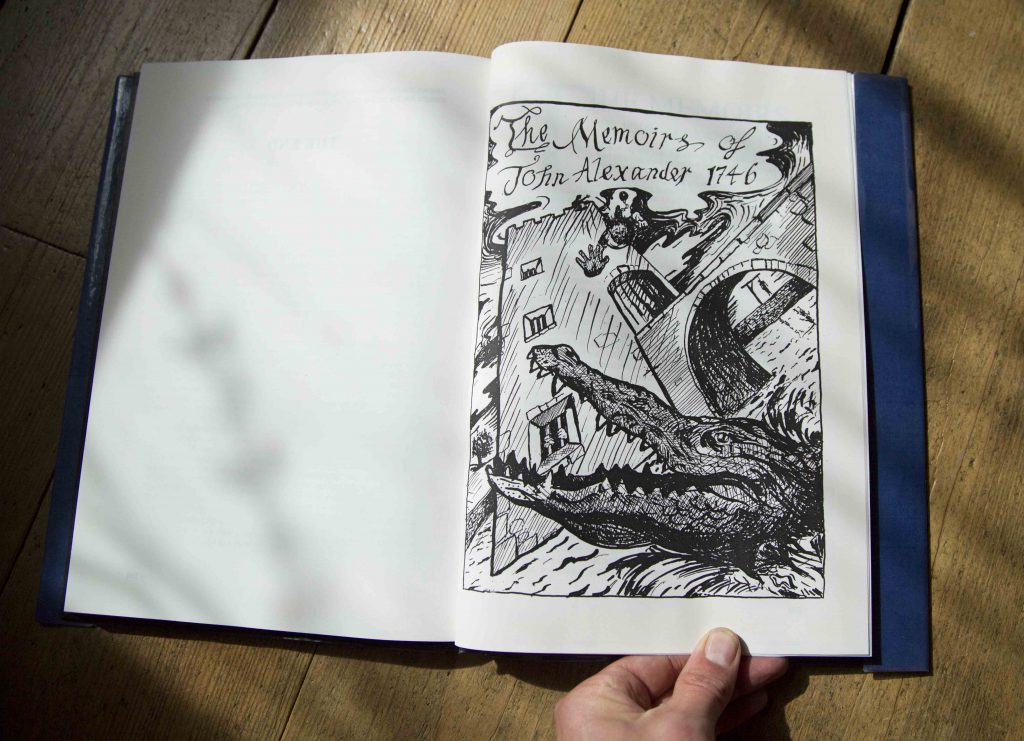

The cover of the version sent to Terry Gilliam. The book was developed considerably after this point.

PP: How did the humour in it develop?

Colin: I think we had the humour in the beginning, but we weren’t brave enough to write it down at first. By today’s standards it isn’t that extreme, but in places it is pretty extreme humour. There’s the bit, for example, where a granny gets murdered because the characters can’t be bothered to save her from vampires, but that is the sort of thing that made us laugh, so we started writing down what actually made us laugh and stopped being worried about whether or not that made us seem like sick individuals!

Tom: We found that we both enjoyed black humour and dark irony and developed our own style of delivering it. A lot of it is to do with pace. In a film you can control the punch line’s timing through the edit and have it delivered in an instant. Words have to be read, so we found a way of pacing the jokes with words and situations.

PP: Did you try to get it published back then?

Tom: Yes, we tried at various stages. I think we might have sent off some very early examples to publishers, but although us two could see the potential, the writing wasn’t very well developed at first because we were so young, and it would have put off publishers for sure. At some point in the 1990s we had a draft that was, I think, 54,000 words, and we sent that to Terry Gilliam’s production company and received quite a nice letter back.

Some time after that I reviewed what we had done up to that point and decided that it needed more development. I spent a long time expanding on the text that was there, replacing the weak bits and tying it all together a bit more. Essentially, it’s origins as a set of stand-a-lone stories was still too evident in places, even though we had already done a lot of work tying them all together. Through the process of bedding everything in properly the book almost doubled in length without me really doing much other than expanding what was already there and improving weaker sections in various ways.

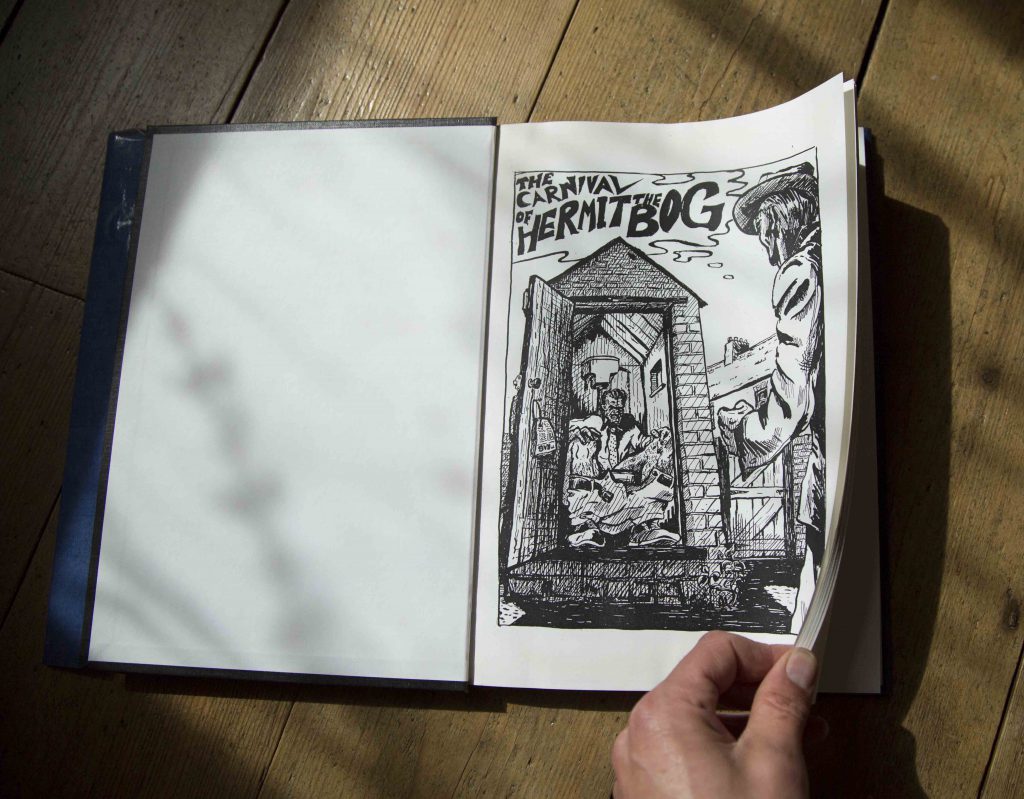

An illustration in a home-made draft of the book

PP: What demographic is the book aimed at?

Tom: Well, we started it as teenagers and it still has many elements that an inquisitive teen mind might enjoy, but we’re really old now and we still laugh ourselves to tears over certain parts of the book. I’d say ages 14 to maybe 24 would enjoy it most.

Colin: Given that we were pubescent boys when we started writing it I guess you’d start there. And when we finished writing it we were rapidly approaching middle age, so anyone in between really.

PP: Can you tell me about the Don Colebox character?

Tom: Yes, he’s Jim’s arch enemy. Like Professor Moriarty in relation to Sherlock Holmes. The adversaries in our book had at one time been friends but their lives went in different directions. Don is self-styled master criminal, head of a hapless gang of imbeciles. Jim and Don are in a game of cat and mouse throughout the book, leading up to their inevitable showdown.

PP: What are the main themes in the book?

Tom: I guess we are looking at the absurdity of life and death quite a lot and the way that it is dealt with through religious stories. There’s also a lot of playing with the idea of reality. As humans, we like there to be a division between reality and fantasy and we use all sorts of things like science and data analysis to separate the two. But the reality of reality is that it is intangible. We mess with that a lot.

PP: There seems to be a lot of circularity in the book, with themes reoccurring and situations coming back on themselves. What’s that about?

Tom: Ah, I can tell you’ve read it all the way through! Yes indeed. In 1992, I got into a situation which was genuinely life threatening and it made me really consider what life might be about. I came up with a bit of a concept, which I won’t delve into too much here, but essentially it is the idea of circularity. As you point out, there is a symmetry to many events in the book and some of the things that seem really random early on turn out to be vitally important later on. It’s a very satisfying book in that respect, but you need a bit of faith in it at the start. Although it’s just a construct in our story, I think that theme has something to say about life itself.

Colin: The circularity partly comes from why we think we are here. Reincarnation is not the right word, but it is the fact that you are going to come back in some shape or form. It’s to do with the circularity of life itself.

PP: What is the idea behind the Carnival?

Colin: Carnival is a time when normal social standards get suspended for the duration of the festival. During that phase, anything is possible. That fits in with the story we are trying to tell because anything is possible, certainly for Jim Leighton, including surviving many times when he probably should have died!

Tom: There is a carnival that happens in the book, but the whole book is imbued with the spirit of carnival.

PP: What about the ‘Hermit The Bog’ bit of the title?

Tom: Well, that’s an example of the absurd. There is a whole philosophical concept called absurdism, which relates to what I was saying about the intangibility of reality.

PP: I assumed the Bog bit was a reference to toilets. There is a lot of toilet humour in the book, why is that?

Tom: Life is a dirty, messy business. When we are born our mothers usually deliver us along with a poo which the midwife quickly clears away. And there’s loads of blood, sweat, fluids and membranes. Being a baby is all about sicking up milk and messing our nappies.

We try to create an illusion of hygiene and cleanliness, but our bodies are full of parasites and germs. I’m not just talking about worms. There are even parasites that live in the eyelashes and hair follicles of all of us

In the 18th century there was a fantastic political cartoonist called James Gillray who delighted in drawing the aristocracy on the toilet. One of my favourites of his is called National Conveniences, which shows several national stereotypes using the loo. His subjects are also often shown belching and being sick. It’s those bodily functions that we as modern humans try to deny, and that’s what’s so funny.

The father of an old school friend of mine was an American ex-Vietnam veteran and when he thought that someone wasn’t genuine or too good to be true he used to say ‘His shit don’t stink!’, which is a similar kind of thing.

Also poo is the essence of life. It really is. It fertilises the soil and from that everything that we need to survive grows. Dirt and decay brings growth, so it’s the circularity idea again.

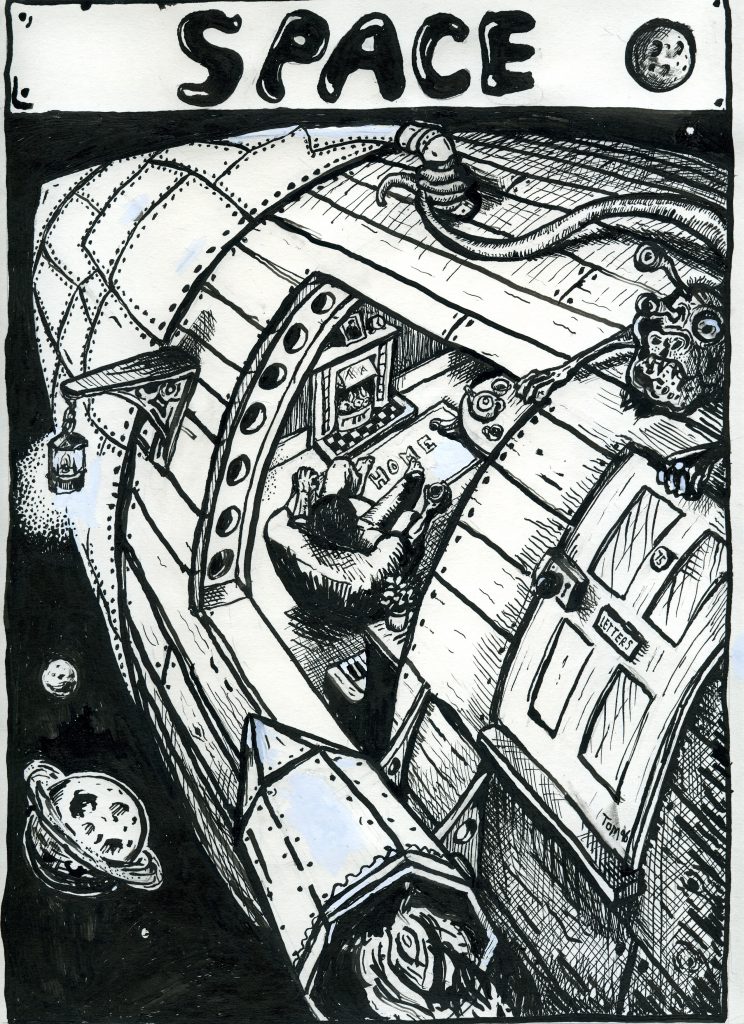

An illustration created for the ‘Space’ section of the book.

PP: What would you say to someone to convince them to read it?

Colin: It’s a journey through life. You can draw a lot of ideas as to what the point of life might be and then choose your own interpretation of what life might mean from that.

Tom: I’d say ‘Stick with it, it’s not quite what you think!’ And afterwards I’d say ‘I knew you’d be surprised!’

PP: What have you got out of doing it?

Tom: It’s a world I have inhabited. I’ve lived it while writing it. The characters are almost like real people to me. And it has been great to share the project with Colin and know he has experienced something similar to me.

Colin: I’ve been challenged to think about what the point of being here is. I’ve had to figure out what I believe in. Even though I have never believed in a religion, I needed some ideas to believe in, and by writing the book I’ve managed to decide what I believe in. And also had a damn good laugh along the way.

PP: So is the book like a bible in a way?

Colin: Kind of. It is kind of the way I look at those books like the Koran and the Bible and those kind of things. I don’t think it is literally what happened, but it is a good set of rules as to why you might want to live your life in a particular way.

Tom: It’s certainly our bible, so that’s two disciples at least! There are many more gags in it than your typical bible, of course. And it is irreverent about almost everything you can think of, including itself!

PP: What’s your favourite bit in the book?

Colin: That’s really difficult to answer because there are many bits that I like so much that I am able to recite them from memory. Those are the bits that stick with you. There’s a section Tom and I refer to as ‘There is a cabinet…’, which I love, and another bit called ‘Flight Over Dogwood’. I can remember sitting on a bus somewhere and opening my old fashioned paper mail and there was a note in it from Tom. I had no idea what it was about because it was just a sheet of paper with absolutely no introduction or anything on it to say what it was. It was just a piece of the story called ‘Flight Over Dogwood’. So I started reading it out loud and everyone around me was laughing because it was such a strange story.

Quite a lot of the book got written like that. You would suddenly get something from the other person and that would fire off a whole new idea in your mind. Part of the time when we were writing it we lived hundreds of miles apart, so that was pretty much how things happened back then. Something would appear on a piece of paper in the early days, or electronically later on, and that would fire off your imagination or take the story in a direction that you’d have never have thought of on your own.

Tom: It is hard to pick one bit. Probably something from the Space section. There’s a bit where the surviving members of the rag tag criminal gang are stuck on a ship with little to do, so they begin developing their bizarre interests that are a leftover from their past lives on Earth. I remember putting that bit in and thinking that it was vitally important in some way. PP

The book can be bought here: Carnival

Another illustration from an early draft of the book. This one was for a rather crazy section at the end of the book.