In Part 1, Thomas Flint explained why he uses found materials to make art, and describes a project which helped him focus on what his work was about and where he wanted to take it in the future. In Part 2 he describes how his working methods enabled him to produce an overseas exhibition from scratch in less than a month, using discarded materials and just a few basic tools.

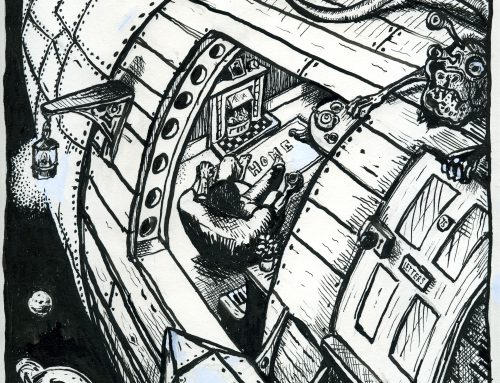

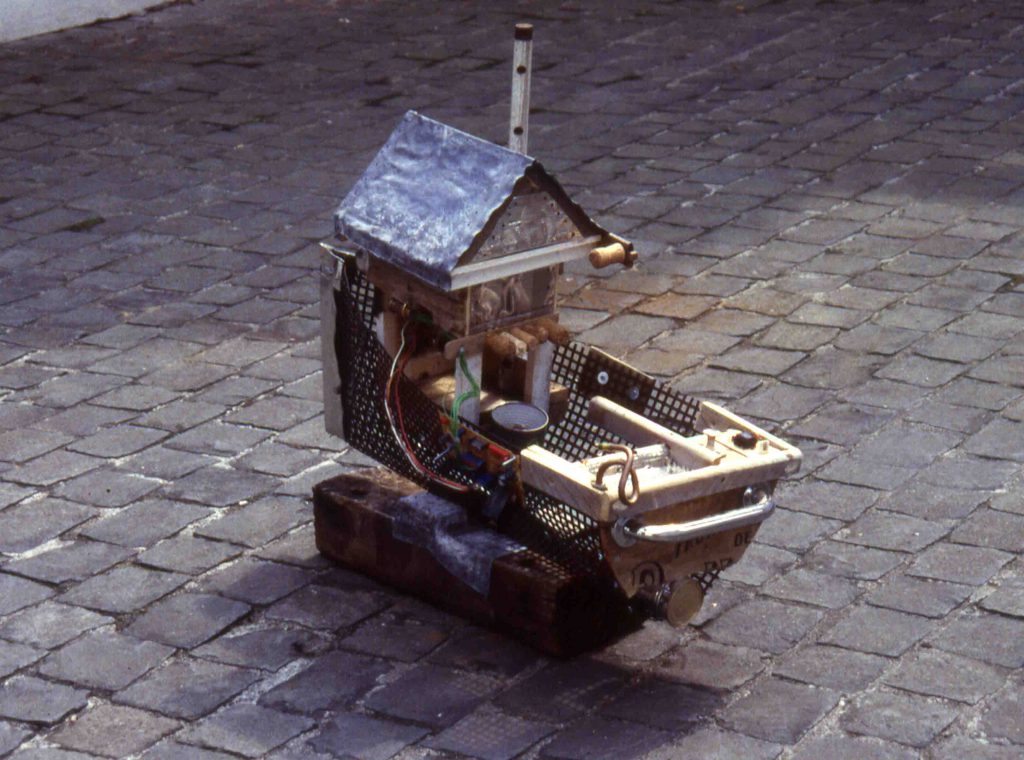

The Ark, made almost entirely from discarded materials. Pictured here in Speyer, Germany

One of my most memorable artistic experiences was a month-long residency in the German city of Speyer, which is situated on the Rhine, not far from Heidelberg. The chance to go there came out of the blue, really. When I was at art school there was a foreign exchange program and several Spanish and French students joined the college. I made friends with them, including a French girl. She was in a relationship with a guy named Eric Verrier, who was a very motivated and enthusiastic French artist. When he visited her, she showed him down to my workspace and we talked about what I was doing.

Some years later, out of the blue, I received a letter from Eric, insisting that I apply for a residency in Germany. I didn’t even know he had my address, particularly as I’d moved house since I met him, but somehow he found me. The residency was five months in a specially-allocated apartment, complete with bedroom, kitchen, bathroom, two large exhibition and work studios and a huge enclosed courtyard. It turned out that Speyer had an extremely vibrant art community which sought to enrich the local culture by sponsoring foreign artists to stay and work in amongst the people.

Eric had just completed a five month residency there, resulting in a public exhibition, and when asked if he knew any artists he came up with my name.

When I received Eric’s letter I didn’t know what to do about it. I was some way into an Arts Administration MA at the time and did not want to stop. The year previously I’d worked various night shifts and in a series of labouring positions to fund the course, and after handing over £3200 for my fees – the biggest lump sum I’d ever had at that point – I was more than reluctant to give up.

Nevertheless, encouraged by a girlfriend to go ahead regardless, I fashioned a portfolio out of some packaging material so that it reflected the style of the work inside, and sent it off to the address Eric had provided. Some months later a reply came back. I had not been awarded the full residency because they wanted someone whose work would contrast with Eric’s, but they still wanting me there and offered me the chance to stay for a month between residencies, soak up the atmosphere and join the artistic community. The accommodation was free and I was to be given the equivalent to £400 spending money.

The fact that I’d only been given a one month residency, rather than a five month one, was perfect. There was no way I’d have been able accept the full residency due to my intensive course, but the single month happened to coincide with a two week Easter break. I went to my course leader and managed to get a little more time off on the proviso that I completed my coursework either side. And so, armed with a few tools, including my glue gun, I flew to Frankfurt, caught the train to Mannheim and, after calling the number I’d been give, was driven by one of the art committee members to my temporary home.

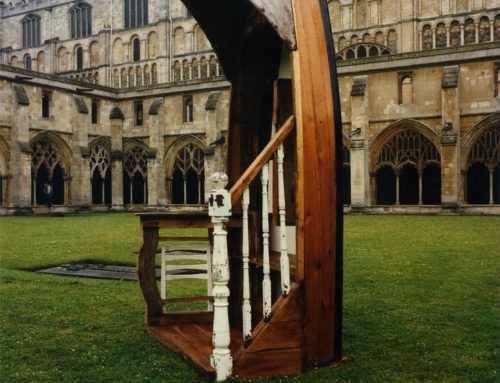

Thomas Flint in Speyer residence. Thomas: “Here you can see me standing in the doorway to one of the two large galleries/workspaces. The other is on the right. I had both of these to myself, plus the courtyard. There was a large bedroom above where I’m standing, and behind the brown wooden door that you can see was the bathroom and kitchen. It was a great opportunity for me.”

Working In Speyer

Over the next few days I explored the wonderful city, cycling along the banks of the Rhine, walking the streets, studying the ancient cathedral and finding places to buy food. A steady stream of eminent local artists stopped by, taking me out, giving me history lessons and introducing me to local food, wine and customs. I was told that no one expected me to make any art in such a short space of time, that they were sorry not to have been able to give me longer, and I should use it as an opportunity to explore the local area and relax.

The thing was, I had been working so intently on labouring and academic study in recent years that I was itching to do some art, and had arrived with lots and lots of ideas. Instead of touring, I was determined to make the best of the opportunity I had been given, and immediately began gathering materials to work with.

After a week or so, the visiting committee members were astonished at how much work I’d done, and asked if I would like an exhibition at the end of my stay. Naturally I jumped at the chance, and worked even more furiously. I had two huge exhibition spaces to fill and I intended to try and do that.

I learnt first-hand how resourceful it is possible to be when you are out of your comfort zone. You are far more willing to ask for help and, without the usual distractions of home, more able to focus on what need to be done.

On one occasion, using one of the bicycles that were left in the studio store room for residents to use, I went on an excursion and I found a television set that had been put out on the street for collection the following day. I rushed back home, used some string and wood to make a television-sized rack for the back of the bike, and then cycled back to get the television. The parts from this went into several sculptures. On another day I noticed that all the high street shops left their cardboard on the streets for collection, so the following week I was able to gather a huge quantity with which I made more work. I had taken the glue gun with me for this very purpose.

One of the cardboard sculptures was photographed in various configurations, and I had the resulting pictures blown up to A2 size, mounted on board, and displayed for sale on the walls of one of the galleries.

I made two other wall pieces which required framing. For this I bought some wood and hooks at an out-of-town DIY store, and cut and joined the wood to make frames using some basic tools I then located a local glass cutter who cut me some panes to fit.

The banks of the Rhine were great for materials such as wood and pieces of metal.

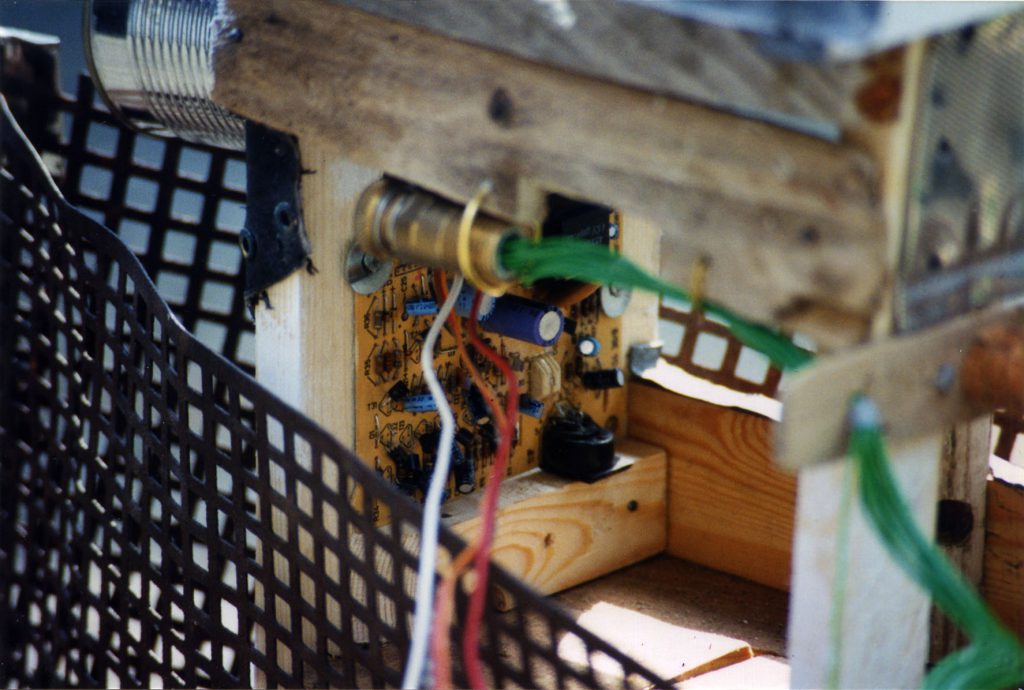

I didn’t have many tools with me so I had to find unusual ways of joining materials, which added to the detail of the works.

In the third week a friend came to visit, which was very timely, as she spoke German fairly well. Through her I could communicate a little easier.

By the end of the month I had been to more social events, dinner parties, exhibitions and artists’ studios than I would normally have done in a year. My exhibition took place and there to cover it were reporters from three newspapers. Speeches were made, pictures were taken, wine was drunk, hands were shaken and some work got sold.

I probably would have found a way to stay out there longer had I not had an MA and dissertation to complete when I returned home.

But the key to my success in Speyer was using found materials. By using local objects I was able to make the work relevant to the city in which it was being exhibited. In a way, I was responding to the environment, and its always good to be able to do that.

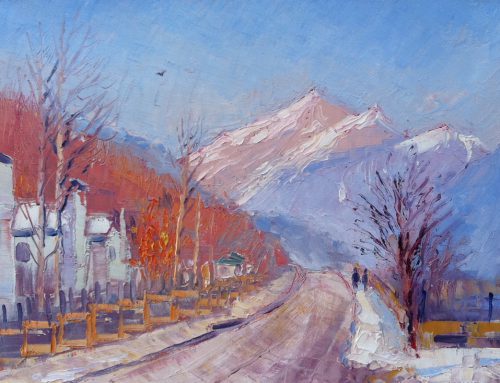

Torheit, Tollheit, Toilet. Thomas: “This was my giant toilet sculpture. I took measurements from the one in the bathroom and scaled it up. I used the writing and images that were printed on the cardboard so that they related to the function of a toilet.”

Various shots of the Torheit, Tollheit, Toilet sculpture

Container 243: Sink with Anchor. Thomas: “This sculpture came before the giant toilet. It also plays with the idea of scale and the water vs cardboard.”

Collecting Stuff

One of the problems with using found materials is that you can easily become a hoarder! Every discarded object, in theory, has the potential to become the basis of a sculpture, or might one day prove to be just the right thing for finishing off another piece of work. At times in my life I’ve accumulated quite a lot of stuff with a view to using it one day, but experience shows that it is far easier to collect materials than it is to make good use of them. Once something has been kept for a while, even if it hasn’t come close to being used, it is hard to get rid of, so to manage things I no longer pull materials from a skip unless I have an immediate use for them.

The problem with not having a supply of stuff in the shed, basement, attic, garage, or wherever it may be, is that when an idea happens to come along it can take months, or occasionally years, to find all the right ingredients. I’m not totally puritanical about every detail though. I don’t for instance hunt around for second-hand glue, screws, nails and paints, but if I happen to be taking things apart, I will keep anything that can be used again. Sometimes items have to be bought specifically for the sculpture, just to get the thing finished, but I always look in charity shops for second-hand materials first.

There is a balance to be found between having too many resources and not enough, and I am constantly working to maintain that balance. Having less means there is more space to work and that leads to good organisation. Having more means that there is a better chance of being able to progress with an idea once it has occurred, although finding your way through or around piles of clutter is not much fun.

I probably should be living on a farm somewhere, with huge outbuildings and courtyards which could be used to store materials and for working in. I am, however, in a city where space is limited. On the plus side I have easy access to hundreds of second-hand shops, tool retailers, material suppliers and, of course, plenty of skips.

The Ark from another angle. Thomas: “Many of parts were found along the banks of the Rhine.”

The Ark. Close up of the cabin

The Ark.

Interaction

The biggest problem is finding buyers who have enough disposable income to pay what a sculpture is worth. Complex ideas can take a long time to make, particularly if certain items have to be found and tested for compatibility with the rest of the piece. The average salary in the UK is something like £26,500 a year, as I write this, which works out at roughly £500 a week. Even a fairly simple sculpture can take a week or more to plan, design, construct and finish so quite a lot has to be charged for an artist to make an average living and cover their expenses. But most people are not willing or able to pay hundreds or thousands of pounds for what is essentially a luxury item. (In fact, even the very rich don’t like to spend lots of money on art unless they feel that they are investing in the work of someone whose value is going to rise).

I fully appreciate this situation, which is one of the reasons why I like the idea of sculptures having practical functions as well as just ornamental and entertainment ones. Another reason is that sculpture takes up space, in a way that painting does not.

My aforementioned boat sculpture is a good example of something which functioned as a seat, and had the potential to be installed in a garden or tall room.

Some may argue that if a piece of work has a practical function, then it ceases to be art, but I disagree with that. For me, the more interaction people have with an object, the closer they look at it and the more they think about it. I am also aware that people with less money tend to have less space, and so art with a practical function is intrinsically less elitist.

I hope that people looking at my work enjoy the experience and start looking at their junk a little differently. They may have no further use for it, but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t useful, attractive, or valuable in some way. PP

To see some more examples of Thomas’ work, please take a look at our gallery, which can be found by clicking here:

Making New From The Old (Part 3: Gallery)

To return to the first part of this interview click here:

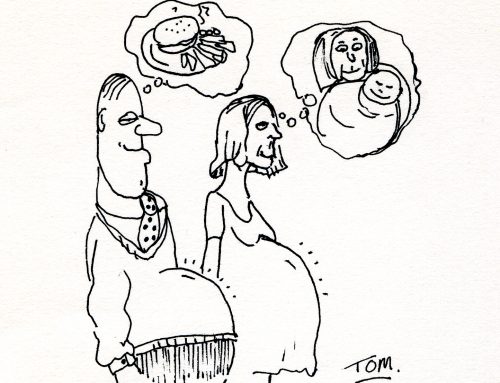

A baby in the boat!