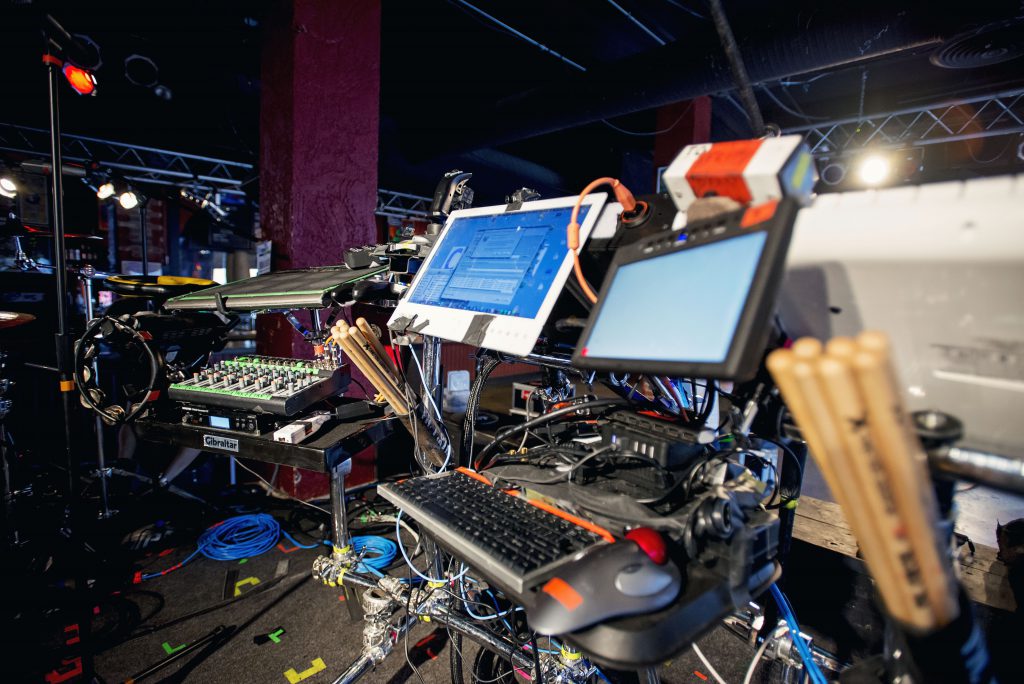

“I kind of reverse engineer all my tunes so I can play them live with my equipment, so most of that live gear I don’t really use that much in the recording process,” admits Robert DeLong, instantly quashing the preconception that his one-man live performances are an accurate representation of his studio recording methods. Films of him in action, which can easily be found on YouTube, show him seamlessly mixing live vocals, drums, percussion and synthesizer lines with pre-prepared samples, which he manipulates and processes using a variety of ‘hacked’ games controllers.

“I almost do live remixes of my tunes,” he continues. “It all depends on the tune. Some songs I am basically singing and doing weird vocal effects over backing tracks and some of them I am building the songs from scratch by doing live looping and stuff like that. To me it’s all about creating an interesting visual performance that physically communicates some part of the music.

“It’s been a long time developing my thing. It has evolved slowly over time. I’ll try a bunch of different things and see what works: I’ll wait until I settle on something that makes sense for a live performance and then built it into the next gig.”

Background Music

Robert grew up in Bothell, near Seattle, in the US state of Washington and started playing drums at an early age, helped by his father who was also a drummer. At high school he got a taste for live performance from playing in rock and jazz bands, but admits that he was always a bit of a computer nerd too, which led him to start experimenting with recording software like Acid, Fruity Loops and eventually Logic Audio.

“First I’d ask my parents to go halves on a new preamp or microphone for Christmas or Birthdays,” says Robert, “then, as I started making more money, pretty much all I’d spend it on was gear. At some point I had a sufficient quantity of gear to record a band and produce my own stuff.”

After school Robert moved to California to study music, and began a performance degree which included an element of audio engineering. He soon found himself recording other bands using a garage studio he shared with a friend (who now does Robert’s FOH sound), but continued writing his own songs and playing solo shows on the side, gradually honing his very distinctive style, which has been likened to Electronica, EDM and moombahtom. Eventually Glassnote Records spotted Robert’s potential and released his debut album Just Movement in June 2013.

For his latest LP, In The Cards, Robert worked with a number of other songwriters, mix engineers and producers, and in other studios besides his own, altogether resulting in a far more mainstream commercial product.

“The first album was definitely five or six years in the writing and that was an amalgamation of a lot of my younger stuff,” recalls Robert. “It was a kind of rave-type, continuous play, album, whereas this one is more of a collection of songs that explore a lot of different areas and genres of influence on me. To me, each song stands on its own a lot more than before. I also got the chance to explore my vocal range a little bit more, so the album has different styles of singing on it. On my first album I was like ‘I wrote these songs, I guess I have to sing them!’ and now I think ‘Well, I’ve been singing on the road for three years, I think I’m a singer now, so let’s try some stuff.'”

Although some of the album’s songs were co-produced (production collaborators include Jesse Shatkin, Tommy English, Andrew Goldstein, Tim Pagnotta and Emanuel Kiriakou), the bulk of the groundwork was carried out by Robert himself, using his home studio setup.

“”On this album I had the opportunity to work with a lot of different producers and engineers in their studios,” says Robert, “which was awesome for me because I had access to a lot more equipment, preamp options, and that kind of stuff, but I’d say that probably 75 to 80 percent of the recording was done in my home studio and produced on my laptop.

“To be perfectly honest, my studio is pretty standard as far as the stuff I use. I have my computers where I do all my electronic programming and that kind of stuff, then I record vocals either at my house or in somebody else’s studio, and if I am going to record anything more complicated like drums or other instruments like analogue synths, I’ll go to a bigger studio.

“My current studio is in a detached backhouse in Los Angeles. It’s obviously a lot more professional than my old garage studio but at this point we’re on the road probably 25 days a month, so although it’s a good spot for me to come back to it’s mostly a rehearsal space, and somewhere I can cut vocals or mix tracks if I need to. I have a nice mic, a nice preamp and my space to record. That way I can control my own fate and stay up to three AM recording vocals and getting into the zone.

“I’ve been using Logic since 2004 and that’s my go-to production software. For live I’ll use Ableton Live, Logic and a bunch of other stuff, but Logic is the only thing I’m quick with. It’s my thing and I love it, but the word logic is a misnomer!”

Production Process

The 11 tracks on In The Cards all feature Robert’s distinctive vocals, which are typically processed and layered and often dramatically re-pitched and tuned. The tracks also all share the same precise synth and drum programming and highly compressed production. Nevertheless, the song styles vary from one another quite significantly, ranging from the ultra-modern chart pop of ‘Jealousy’ to the rave influenced title track.

‘Don’t Wait Up’, on the other hand, is reminiscent of ’80s pop, while the powerful ‘Long Way Down’ takes in elements of hip hop.

“Every track starts in a really different way,” insists Robert, specifically referring to his writing and pre-production process. “The common denominator is that most start when we’re travelling on an aeroplane or in the van. I’ll be wearing headphones making a beat or working on some synth stuff. So I accumulate all these demo tracks that have no vocals on them.

“When I am on the road it’s a lot of sample libraries, cut-up loops and I use a lot of soft synths too. Once I start to formalise the thing, I’ll often replace my sample libraries with either my own recorded samples or more unique sounds, and then I’ll rebuild the track so much during the production phase that it replaces 90 percent of what I’ve made at the beginning. But I find it’s a good way to get started and it is quick and fun to work that way on the aeroplane.

“I feel like a lot of the sounds on this album are classics, like Roland 808s or 909 sounds, so the samples generally sound the same regardless of their origin. And there’s actually a lot of my live drums on this album. It’s fun to record some real drums and replace that stuff, but you’d never know because there are still layers and layers of samples with my drums, as well as compression and weird stuff.

“As far as choosing samples goes it is pretty arbitrary. I have thousands of kick and snare samples and I throw in whatever fits the vibe of track using the Logic sampler. As for soft synths, my go-to right now is Uhe Diva. Diva is a standard additive soft synth and sounds pretty classic. I wouldn’t say analogue, but you can make it sound like a Moog or a little bit like those classic synth sounds, and for 90 percent of the synth work it’s pretty much classic sounds I’m using. I’m not doing anything crazy.

“What I did a lot on this album was use the Roland Juno synth to replace some of those Diva sounds, but sometimes it is the same result either way! When you walk into somebody’s studio and have access to some cool modular synth you end up hooking it up and getting a sound, but sometimes it’s just a dirtier version of the sound you’ve already got and no more helpful. I find that happens a lot. For me anything that speeds up the creative process is good, even if it is not the coolest story to tell people.”

It’s clear from listening to Robert’s album that a lot of trouble has been taken to ensure that none of the tracks are lacking in the low-frequency energy that is so important in modern pop, dance and EDM genres. As it turns out, most basses are composite sounds comprising top and sub elements.

“Every song has a different bass line but a lot of the time I recorded my synth top bass and then put a sine wave that I’d generated with Uhe Diva or the Logic sampler as my sub running underneath,” explains Robert. “So I’d do a high-pass filter on the top bass and have the sine wave underneath for that sub-bass information which you can feel but are not really hearing that much.

“Probably 40 percent of the album’s top-line basses are Diva. Then for a couple of tracks, including ‘Pass Out’, which is like more of a drum and bass kind of track, I use Xfer Serum, which is a soft synth that’s only about a year and a half old and is super modern sounding. It sounds a little scary and can get grossed up pretty quick but it sounds good. It’s like (NI) Massive, but a little more house leaning than Massive, which is always leading you more towards drum and bass.

“Massive is on there one time too, I think, but in a way you’d never really notice. And for bass on a couple of tunes we ended up using the Juno and something really messed up like an Omnichord. But once I get those four notes down I’m cutting them up and moving them around for a lot of those things.”

Beat Mixing

Given that Robert started out as a drummer and always plays a kit as part of his live stage show, it’s not surprising to learn that some of the album tracks feature drum and percussion parts played by Robert. Nevertheless, a lot of samples also make up the mix so it is rather difficult to tell where the real drums end and the samples begin.

“There are three or four songs that have real drum kit.” reveals Robert. “The first track, ‘In The Cards’, has big housey drops, and all those kicks and claps and stuff are samples. Most of that stuff is filtered 808s and 909s with lots of compression, EQ and layers. On ‘Don’t Wait Up’, those are my real drums layered with some white noise snares. They were recorded at Tim Pagnotta’s studio. He’s done a lot of alternative pop rocks stuff. We were using a cool old kit that is pretty similar to my dad’s old ’60s Ludwig kit that I still have. It was tuned way down and stuffed full of pillows and we spent about an hour and a half tuning the kick because the thing was really temperamental. I can’t remember what mic configuration we ended up using on that because we went through a bunch of different options, but I think it was pretty standard stuff like Sennheiser 421s on toms, Shure SM57s on snares and then Royer ribbon room mics.

“Then there’s ‘Born To Break’, which is a combination of pitched down sampled drums and a real drum kit in a different studio, and that was I think a Yamaha Maple custom kit. It was all about getting the groove with the ride cymbal and maybe some of the ghost notes on the snare drums, just to get that live feel and create some room to breathe. That’s a lot of it for me. I ended up cutting it into a loop anyway, so it’s a one bar loop of real drum sound over the samples.”

To give his kick drum a feeling of power, on many of the tracks Robert inserted a compressor into the live drum mix-bus and fed a kick sample to the processor’s side-chain input, which triggered a monetary duck in the level. Robert explains his methods.

“A lot of time I’m side-chaining the entire drum bus so every time the kick sample hits, the drums immediately get quieter, because it’s set with a really fast attack. Then it slowly releases. So you can hear the overheads disappear for a second and then fade back in, and that gives that kind of crazy ultra-compressed pumping kind of sound. There are a few moment in the record where I have fun cutting up stuff with that. It messes with the groove but it is a fun way to make it feel like you are always oozing into the next beat. It’s all pretty subtle stuff.

“Then for those big drum fill moments — because there are some big ’80s Phil Collins drum fill moments on the records — those are all real recorded toms, overheads and close mics, doubling up with some really hyped samples and all sorts of terrible things like gated reverb!”

Part 2 of this interview can be found here