In the mid 1960s, Slade Art School graduate Colin Self became recognised as one of the leading figures in the British Pop Art movement, renowned for his draughtsmanship and Cold War themes. Never entirely comfortable with the commercial art world, Colin eventually moved to Norfolk – the county in which he’d grown up. He talks about his path through art school and how he has managed to continue living as an artist.

The tools of the artist! PP

When I was five I went to a school the Norwich Parish of Thorpe and was taught by a Mrs Grimble. She was Grimble by name, Grimble by nature and gave me bad dreams. Although that school has changed enormously, and it’s a really bloody good school now, I have to say in the 1940s it was just too regimented, too modern and too Mrs Grimble! But then I had a stroke of luck.

It was just after the war I lived on a dirt road in Sprowston called Greenborough Road three miles north of where I live now. My parents paid our rates to Sprowston but we still went to Thorpe school. There was a Christmas party and the children from Greenborough Road were allowed to go to the party, but we weren’t allowed to eat the food because our parents paid their rates in another parish. So several of the parents got together and took their children out of the school and into a school in Sprowston.

So then I was at this Victorian school which had been built when it was compulsory education for everyone in 1860 or something like that. It was just a much nicer building, and I had a nicer teacher. She was a lady called Mrs Wyatt, who said ‘I think you are a very intelligent young boy,’ and moved me to the A-stream. And I sometimes shudder to think what might or might not have happened if she hadn’t recognised that and put me up at the top when I was six. So there was this kind of lateral, meatball chance in life where I got moved from one school to another and I really got on with it – at an infant age.

But I think it happens for all sorts of kids all through. If you had got some ex-army type sports teacher and he had it in for you, you’d just never do sports. So that was how it began.When I was eight, in the very early 1950s, another lovely, lateral thing happened to me. My dad’s older brother – my uncle Arthur – was always ill. He had been a bit of a stay-out and a bit of a nutter when he was younger, but for some reason or other he had developed bad kidneys, had an operation that went wrong, and was obviously poorly.

So he’d come up when my dad was at work and try to make something in my dad’s shed; mend a football or something like that. He was a decent bloke. He didn’t have children of his own so one rainy afternoon he took me up to the Norwich Castle Museum.

I saw the work of the Norwich school of painters and it just, to use the old hippy expression, blew my mind away! I can remember seeing dust coming up from wheels of stage coaches and it just gave me this thing when I was eight. Then for years I wished I’d been born in the olden days so I could have been one of those artists.When I was eleven I got a place at Wymondham College, which was a large co-educational boarding school. I got eight GCSs. I always loved art, so from Wymondham College I went to Norwich Art School. I was there from 1958 to 1961 and the painters Jeffery Camp and Mike Andrews came and taught us.

When I was 13 or 14 I thought that maybe I could work on a nature reserve and be like that Peter Scott. I used to copy the pictures of birds out of bird books and my drawings were as good as those in the books. Then when I was 15 or 16, still at Wymondham College, a girl got an art school prospectus from Central Saint Martins College of Art and the art teacher was saying ‘This is one of the best art schools in the country.’I can remember working in the art room at Wymondham and thinking, ‘What’s this school for art? This is too amazing, but it’s London and I’m not going to go all the way up there. I’ve only been there once.’ Then two other boys, Roger Fisk and Lenny Burgby, got prospectuses for Norwich Art School and I thought, ‘There’s one in Norwich now? This is just too much!

When I got to art school, I have to say that I was a bit, snobbishly, slightly taken aback that there were students at the school who had zero GCEs and I had never failed one. I wasn’t academically brilliant but I could always pass because I was a grafter.But after a week or two I started to realize that, although there were people there without any GCEs or academic background, they were good at art. It was maybe the first time I actually understood that, like athletics or football or being born with a good voice or good pitch, art is visual and the whole process actually happens in a different area of the brain to logical or academic thought.

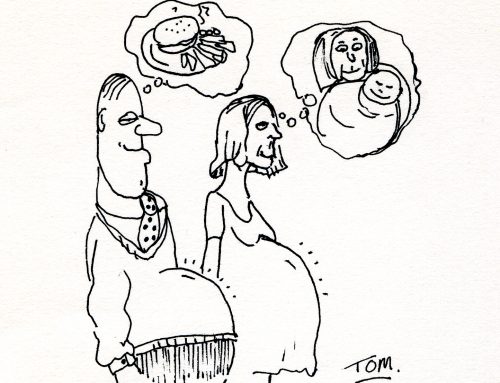

So for a few days I was thinking, ‘Well I’m in a class with him and he hasn’t got any GCEs, how can this be?’ But only for about a week and then I started to see that these people were actually wholesome and had something.So ever since then I have been against trying to make art schools and the study of art and the learning how to sculpt or paint or be a great potter or whatever, into something academic. You could, for example, have an academically bright professional footballer, and there have been plenty, but you could also have some who are dyslexic or something like that, but when they are on the pitch they are just brilliant. That’s my view. Colin’s Victorian Primary – safe from Mrs Grimble!”

Starting at Art School

In those days there wasn’t a huge pressure academically on the students, it was rock and roll, 1958 and we all got a bit wild, I suppose. We were taught composition, life drawing, modelling in clay, then a craft, such as lino cutting, and lettering. So we were taught these old ways of working and I did feel suppressed.

There was also such laziness and chaos at the college. There were several bad teachers and a lot of bad students, with no energy. I was invited to the Norwich School of Art and Design to select student’s work on its 150th anniversary along with a writer and poet from London called Sue Hubbard. When I got there I couldn’t believe that there was still that same thing. There is no sense of the moment and the system is just too big.

If I want to saw a bit of wood I want to just be able to get on and do it; I don’t want to have to ask three people. Then a maze comes down out of nowhere, and then you have to get through this maze and, if you’re a good boy and lucky, you can get a grant for it and write a thesis on it, then four days later you can saw a bit of wood! It’s still there like that and I find it hard to be inspired.

And if there is one thing they hate more than failure it is success. It’s like the Australian Tall Poppy Syndrome. If you get a lecturer who actually rises above everyone, the university and all of the staff gang up and aren’t happy until the guy or woman is out.

So it’s a very, very complex thing and I think possibly you would have to read what Leonardo Da Vinci thought on teaching to actually be in a position where you can get anywhere. If things work in art schools and universities, possibly what Leonardo Da Vinci thought on teaching is what’s going on.

Noel Spencer, the principle, used to say he didn’t push anyone to get the diploma, as it was then, because he thought it would devalue the diploma. He used to say ‘I like to think those who get on will get on anyway, and if you force everyone to end up with a diploma, they won’t be doing anything with it,’ which I thought sounded cowardly, lazy, oldie worldly and quaint at best.

But every Saturday I’d be up at Norwich library and I would invariably be reading two books: I’d be looking at a book on Jackson Pollack and reading the letters of Van Gogh and I never erred. I’d spend the whole afternoon until it was slinging out time ogling those two. So what I’m on about is that these are the people who taught me. I could be taught by Michelangelo, Leonardo or Paul Cézanne. Cézanne has been dead since 1906 and he’s teaching me still. In other words, there’s nothing worse than having a bad music teacher teaching your daughter the piano. There’s a lot of that.

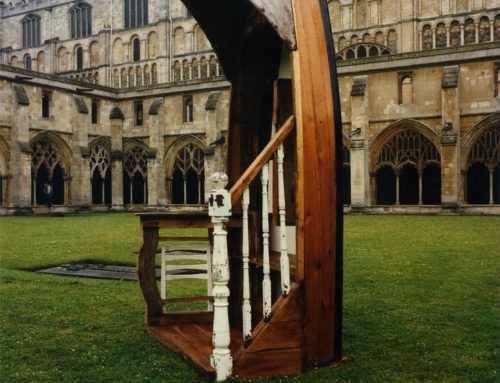

The Art School in Norwich – now known as NUCA (Norwich University College of the Arts)

Being a Student

The great thing I got from being a student, especially an art student, is that it gave me an identity. I’d do summer holiday work on pea vining stations and be mixing with the people who had come off of the dole for some big money in the summer – Teddy Boys saying ‘What the fuck are you doing?’ You’d get a lot of that in cafes and all over and you used to say ‘I’m a student.’ It’s a bloody brilliant thing to be able to stone-wall people if they are trying to get at you. It was a total identity and no one could penetrate my fortress of being a student.

If I wanted to lay in an hour or two later than anyone else; if I wanted to stay up, listen to rock and roll; study on a Saturday; if I wanted to go to pottery lessons Saturday mornings, which I did; if I wanted to live in a dream and be Elvis Presley, Little Richard, or the Everly Brothers or James Dean, well, I was a student.

It’s a fantastic thing to be; it just is completely brilliant, because what it gives you is five years to actually try and reach your inner self, and if you are going to chip in your two-penn’oth for humanity you’ve bought five years to do it. It’s a fantastic thing and in a sense academic qualifications are totally meaningless.

Briefly, there was a moment when I think working-class kids of my generation had it good. My dad is a wise, and slightly eccentric, pub musician who worked as a sign writer and painter and decorator, but two or three years ago, while he was decorating my house, he admitted that in the late 1930s he got a place at Norwich School of Art, but just didn’t have the money to go. He was the family’s artist but just never had these breaks. I never had a clue.

His father was gassed in the First World War so he was brought up from one back street to the next throughout the depression in Norwich. I think the war pension then was 10 shillings a week. He even went to friendly societies to try and get the money but the repayments were five or six quid a week which was like a whole person’s wage. And he just hated me going to Norwich School of Art and did everything he could to make me leave, but I’d done it quite independently.

So it’s almost like I am working for two generations and I guess this thing is happening again at universities with grants or loans. Imagine all those brilliant kids ending up in crime of sniffing glue. I don’t know what’s going on. I personally think genius can be born anywhere to any race or class anywhere in the world and mankind should have a system where you reap it, not suppress it. I suppose I have got an old-fashioned Clement Attlee or Aneurin Bevan type notion, because they kind of gave me my breaks.

Photo by Sian White

Going to the Slade

I was at Norwich for three years before going to the Slade School of Fine Art for two more years.

I was painting intently in the Norwich life room when I heard Ian Chance, who now runs Wingfield College, talking semi-grown-up talk in the corner of the life painting room with Mike Andrews. It was a bit like The Famous Five! I could hear Ian saying “Bla, bla, bla, bla, bla, bla, Slade School, bla, bla, William Coldstream, bla, bla, bla, interview,” and I thought, ‘There’s somewhere else on from here, is there?’

I think there was six weeks left to apply and I can remember thinking. ‘Bloody hell, there is no way I can do this in six weeks!’ Then I made my mind up. I thought ‘Right, Ian’s trying for the Slade and he’s getting himself geared up and ready. I’m going to start working my rocks off as if I am going in for the Slade School Scholarship entrance with Ian, but I am not going to do that. I am going to leapfrog on and try the year after. I just wanted the best I could go for and get.

Mike Andrews used to think that the Royal College was certainly very, very good in fine art but The Slade was more deep thinking. Maybe more messed up but more deep.

David Hockney came into The Slade one night with a Norwich guy called David Rand, who was a fellow student at the college. It was ‘The Slade hop’, which we used to hold every now and then.

David Rand was a quite a forward, aggressive, domineering kind of a bloke. He said ‘Self! Let’s see your work.’ And I remember thinking ‘He’s with that bloody, blonde David Hockney bloke.’ So I went upstairs to the corridor where I had a big pile of my weird, shaded drawings and some paintings. Rand saw my paintings and started spouting forth: ‘It reminds me of Sidney Nolan, it reminds me of Robert Ellis.’ I thought, ‘Well, I don’t know Sidney Nolan, I don’t know Robert Ellis,’ and he said, ‘No I don’t like it.’

Hockney was just looking through my weird drawings and at the end he looked up, sort of checked his glasses and said ‘Well I think they’re very good.’

My Norwich friend wished he could vanish and I became mates with Hockney then. That was another thing that just happened, so that’s how it works as well. We have drifted apart but I still call him my friend and apparently he still calls me his friend and is very fond of me.

I’ve had some strange discussions with David Hockney. He was so sexually radical, he used to say things that made me cringe when I was a 20-year-old homophobic, weight-training, macho bloke, not totally sure of myself. He had this huge kind of cerebral wit coming off him all the time; zany, and this inner determination.

He once asked me how I got on when I went to art school and I said ‘pretty good.’ He then told me about when he first went to Bradford art school. He was dressed and looked like a school boy, with national-health glasses.

He said ‘When I was at art school, I were in the life room trying to draw the model and all the other students – they’d all fucked off – but there was this one student who was older. He was grubby, had jeans and motor-bike jacket and all that.’

This bloke was leant back on his chair impressing his girlfriend who sat next to him and spent the whole class taking the piss out of Hockney saying things like ‘Eh, look at him, he’s a real artist, he is, he’s fuckin’ drawing.’ And Hockney said the girlfriend just was laughing all the way through thinking this guy was smart.

I remember Hockney telling me this in his flat in Powis Terrace in 1962 and it fucking scared me. He said ‘after this bloke had done all this piss taking I just thought, “I’ll fucking show him!”’ and his mouth just grimaced! His top lip went down at the edges to this strong jaw of his and I can remember feeling funny – there was such a kind of tight energy. I mean, I have a lot of will power and I can get really like a ferret down a hole in the pursuit of creative ideas, but I think Hockney had more willpower to succeed than me. Suddenly the doors and curtains were drawn open and there was this willpower that was like nobody else’s I have ever met.

Alex Ferguson the football manager hides that inner willpower quite a lot. When he comes on TV he has that school boy hair cut and he’s obviously relieved after games but just says ‘Oh well it went quite well actually.’

I would have thought you certainly have to have that to be an artist, but without being those awful metal-welding, silly sculptors from St Martins. You know? All those lumpy people with chips on their shoulders and sculpture dust on their arses – those heavy people. I don’t mean that kind of malevolent, fucked-up thing you get off of them. TF

See Part 2 of this interview for more on Colin’s life as an artist.

Part 2 can be found here: Part 2