In Part 1 of our interview Colin explains how fortune took him from modest beginnings to The Slade art school in London where he met David Hockney and Peter Blake. In Part 2 he explains what happened after he left The Slade and found fame as a leading light of the British Pop Art movement.

All photographs by TF unless stated otherwise

Expanded Horizons

When I was 20 I went to America. I’d saved my pea vining money up one summer and got hundred pounds premium bonds money put away. I’d had a bit of love trouble and was feeling totally on my own. I was just going down to the refectory in University College when I saw this poster which said ‘London to New York £44 return’ and I thought, ‘I’ve got that.’ I can remember thinking, ‘I’m bloody doing that, I’m going to go.’

I didn’t know how. I did it almost as a dare to myself because I felt so low about love going wrong, as young people do. And I did it. The London School of Economics had chartered an aircraft. I hitchhiked 8000 miles, got down to Tijuana in Mexico, got ahead of time and went up into Canada and hitchhiked through Ontario and came down at Niagara Falls. I went all over the show; all across on route 66. And I just met so many people, including a few ladies. I was always quite shy but I even got a little bit of a girl friend in LA, which was brilliant.

I went there with £50 and slept out for about eight weeks and stayed in two LA addresses for three weeks each as well, so that would have been six weeks on the road. It’s always about life presenting chances and either you take them or you don’t.

I’d got so brassed-off with the Slade. Two lecturers had been badly on my back. One was Thomas Mollington, my tutor. We were too alike, in many ways, to get on. Later he became Sir Thomas Mollington and president of the Royal Academy. I was in a caravan in Scotland when I switched the wireless and heard the sad news that he had died.

But he just couldn’t understand what I was trying to do or where I was coming from. He wanted my Slade time to be spent like an apprentice. He was always telling me I should get back in life room, draw this or that model and have that period as my apprenticeship. That was bound to fail.

Andrew Forge was a lecturer at the Slade who literally tried to get my work into the Slade’s worst three student’s category – doomed for failure. And I gave him such a Norwich back-street mouthful that it kind of rattled him, and thank goodness because the other two failed – they never fought back at the system and finally got a 50 percent pass. When I was at Norwich I was never believed and when I was at the Slade I was never believed.

“But I was mates with tutors like Keith Vaughan, a lovely artist who’s also now dead. He was totally liberal and his students were on a different plane.

But by the time we came to our last two weeks at the Slade, various students, who had been academically well in and decent, were suddenly looking so bloody nervous. But I suddenly became imbued with this supreme self-confidence and I thought ‘I can’t wait to get away, I’m going to bloody show them. Look at them. They are all in the corner trembling.’ And I just suddenly felt like that it was my moment.

The Slade as it is today. Photo by Sian White

After The Slade

That summer my girlfriend became pregnant, so when I left the Slade in 1963 we got married. I had no money but it didn’t worry me. I worked that summer at Bridseye on a pea vining station and got what was big money then. Probably three or four times the national wage at the time. I was doing 12-hour nightshifts non-stop, seven days a week. Then I worked for Laing Construction for a little while, building sugarbeet silos and raised some money. Which obviously my ex-wife’s white-collar, working-class parents thought ‘This is just appalling.’ But I thought I was getting quite made up.

Also, David Rand, the villain of the piece who introduced me to David Hockney, dragged Peter Blake up to Norwich in the summer of 1963 to do a criticism at a Norwich Twenty Group meeting. They used to meet above the Festival House pub and have arguments and stuff. I used to go along as a student and Mike Andrews went to a few. I remember Mike coming in half-cut once or twice and we’d stand at the back.

“Peter Blake had done a crit

So I got to hear of Peter’s visit and took a folder of drawings into the meeting of the Norwich Twenty Group. I only got there towards the end, and I can remember one or two of the local artists being a little bit disdainful that I’d arrived late, but Peter looked through and he bought a shaded chair drawing, which he’s still got, for three pounds ten shillings.

I remember taking it back to my ex’s bungalow in the suburbs and showing her mother thinking ‘Look at this! Peter Blake’s bought a drawing!” and she was decidedly unimpressed. It was a third of a week’s wages then, if you were on the bottom scale, but I just saw door opening. Imagine if you were good at hockey, netball or music and suddenly a teacher said, ‘You’re in.’

If you are on the enterprise allowance scheme, it’s hardly the way they would suggest you start a business, but that’s what it was and how it started. I thought, ‘This is it!’

Making A Living

I’ve never known where the next hundred pounds is coming from. Obviously doing group exhibitions is partly how I make a living, although one of Adam Smith’s three great pillars of how you succeed is thrift. No Tory ever talks about thrift, but that’s partly how I have survived. I am the oldest of nine kids and my mother was a good manager – good at making a little go a long way, so it’s partly what I learnt from her.

In 1963 I went to see Mike Andrews about maybe getting work for magazines. Mike thought that it might be a good idea. He was ever so good. He said ‘Let’s make a list.’ I really wouldn’t have minded doing some drawings for Vogue or something like that but Mike said ‘Let’s put Private Eye at the top, you can do that first.’ Then he said ‘You don’t really want to draw for Private Eye, do you? So if that fails, never mind, that will give you some practice. And place Vogue magazine second after Private Eye.’

So I more or less formulated a list and worked through it. I can remember going to Private Eye with a folder of drawings and facing a semi-cynical panel of three or four guys who said ‘Well, we’re political, if you ever do something political, come back, ‘ so that one ended.

Then I saw the assistant art editor of Vogue and he just went ape shit over my drawings and said ‘Oh, gorgeous, wonderful, how much are they? I’ll buy one.’ He wanted a picture of this girl on a sofa. “He was a nice guy called Harry Gordon More; a Scot, I think, but with an upper-class accent so you’d never have known it. I sometimes see post cards of his work. I can remember saying that the drawing with the sofa was eight pounds and he said ‘Oh, is that all? Oh no, it must be more, have ten,’ and he wrote this cheque out! He said I could draw shoes but said ‘You’re too good, you don’t want to do that.’

But I still use the list idea, so if I get a bit low, so to speak, I’ll try to remember everyone who has expressed some kind of interest and made a remark. You can take a point, say, in the last two years. And you may find that you start remembering 12 people who have expressed interest.

After I first got married, by October ’63 my Birds Eye and Laing Construction money was running low and I thought ‘Peter Blake bought a drawing last summer, Mike Andrews was interested, my friend Joe Keys at the Slade was interested, and Terry Atkinson was interested. So I took a folder of new work and went to see Pete one night and he bought a sofa drawing, I think for £8, Terry Atkinson had one for £3.10, Joe Keys had one for three pound ten shillings, and it was like I was doing this whole thing from remembering who had said ‘Cor, I wouldn’t mind one of them.’

But things aren’t like the ’60s: things are slower. In the 1960s you could probably get some action moving within a week, whereas because of bureaucracy and this invisible maze I spoke about, now when you think something is happening the earliest it will start happening is six weeks from the idea.”

But a list is one way and just recently I made one. Then sometimes I do laser prints and ring round various friends and see if they want to have a print at something like twice the production cost. So they are still getting a bargain, but it also means I can do two for the one they want.

I’ve just done a laser print that cost £25 or more to put together – it was £22 for the print plus dry-mounting and various other expenses. I wanted to do it as a small edition. The first friend I called was Colin Barnes who used to live in Norfolk but is now based in South End. He said ‘No, I’ve got a lot of your stuff, I think I want to see it first,’ and it really gave me a complex. I thought, ‘Bloody hell, no one wants to know,’ but the other six people and said ‘Not-half! Yes, alright.’ Marco Livingstone, the author, who is ever so nice, said ‘The thing is, I don’t really like football. But then the next day a cheque came.’

He said ‘After we had our conversation I suddenly thought, “what am I doing?”’ So that’s a nice thing. And he actually bought a 1964 etching as well. But when I was a kid I can remember some Christmases when we’d be really skint and my dad would remember that a builder would have owed him ten quid and I’d have to go round with a note, knocking on the door.

I remember the builder saying, ‘Well, that’s from Ernie, well I don’t know, he want that ten pound, well I just ain’t got it, OK?’ and I’d have to go home and tell my dad that I hadn’t got the money. Experiences like that were the reason why I didn’t feel bad when my Slade School time was coming to an end. I just had this inner belief that I was going to make it.

Greenborough Road – no longer a dirt road

Shared Values

When I lived on Greenborough Road we were all vaguely, what I suppose you’d call, working class, but we knew there were posh people and occasionally we heard someone who we thought was posh. But we were also clever. Some of my friends ended up as engineers, doctors, business men and all sorts, and they all came from this little road. It’s actually quite extraordinary.

I wish I could write a thesis on it and send it Prince Charles, because I don’t think the perfect thing is what he is building in Cornwall, with all due respect, it is more to do with a dirt road and maybe an extended tribe. [Prince Charles is the Duchy of Cornwall. PP assumes Colin was talking about the Prince’s management of the estate – Ed].

We were surrounded by fields and woods, and every week we took the longest bus ride to Norwich, which was called ‘going up the city’. One the way back, if we got off the bus in Thorpe, we’d always have this walk down Woodside Road before we got to our little road.

We could see the stars at night. We learnt all bird song and differentiated between various trees and what wood you would cut for a bow and what wood you would use for arrows and we learnt a lot about animals.

The dirt road was essential because we never had cars coming down at a pace. So I think there are laws which are beyond architecture or what architects or anthropologists theorise about and I think it gave us a hell of a lot of time to dream, project and wonder what the world’s about and what we might try and make of ourselves.

Brüer Tidman, a brilliant artist from Yarmouth and Lowestoft, lived at 20 Greenborough Road when I lived at 32 Greenborough Road, so we know each other from way back. We played together in the woods as kids. Mrs Tidman used to have Christmas parties. There would be all the people in his kitchen at the back and the jelly and blamange would come out and be put on the table.

Brüer was at Royal College when I was at the Slade. I actually went to the college once and I saw him doing an etching of the pier at Great Yarmouth. I went in and said ‘Wotcha, Brüer,’ he went ‘Oh, Wotcha, Colin.’

When he was eight his mum moved to Yarmouth when his parents marriage broke up. The only time I saw him after that was when I was about 13 and we went to Yarmouth and bumped into him on the beach, so the Selfs spent the day with Brüer. After that I didn’t see him until he walked into Norwich art school in 1959 and he went ‘Wotcha Colin.’

When I was a kid I don’t think I ever envied anyone anything and all through my first career through the ’60s and early ’70s, I never recognized jealousy in people. Some people used to get to know you in order to further themselves. Some would almost do anything, like be after your wife when you were away. It was a strange thing that if you were in a book you attracted a certain kind of person.

I’d see the ex-girlfriend of somebody I’d always thought was a friend and ask ‘How’s so and so?’ and they’d say ‘Oh, him, well, I’ll tell you. He used to say “If bloody Colin Self can make it, I’m damn sure I will,”’ and you think, ‘Oh, this was a friend!’

It’s like the Australian tall poppy thing I mentioned. I personally went through ten years of really heavy weather which was to do with all that kind of thing. It’s imperative that you pick out who is there but not actually doing you any good, but I’m still a bloody mug. I still can’t tell what people are on about. But if you are not careful it will kill your own generosity of spirit in a way. But no matter what life throws at me I am hopefully going to weather all the storms.

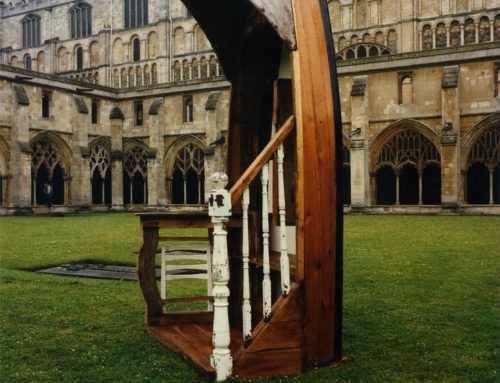

Norwich University College of the Arts

Teaching to Make Ends Meet

When I sold my sofa drawing to Peter Blake in 1963 he said, ‘Look, I’m going to Los Angeles for eight weeks for the Sunday Times. You could have my job as a lecturer one day a week at Walthamstow Art School. Do you want that?’ He phoned Jack Smith, the kitchen sink artist from the ’50s who was head of department, and when he put the phone down he said ‘You can fill in for me when I’m away. You’ll get star wages – they won’t bother to alter the wage structure for eight weeks.’ So I was getting £14 for one day a week lecturing, which I think was more than the national average wage at the time!

Then the principle of Norwich Art School heard that I was teaching in this top London art school and I got this part time job at Norwich. So on and off I did a few bits of part-time work. But about six or eight days a term was what I used to like.

I’d go in and do a two week course a term, or something like that. Then I turned that around so I was actually doing Renaissance type classes where I went in and worked and the students worked alongside. And that’s good because you are showing them you are human. You are doing, not talking, and it puts quite a tension round if you are there until nine or ten o’clock at night working, as I was, and you work through lunch and don’t bother for coffee breaks. Within three or four days they were all working through coffee breaks because they didn’t know how to come back in the room once they had gone out. And you could actually watch people’s work improve in a short time just by being serious about it.

But then there was Ed Middleditch there, and I have to say, Ed was a funny up and down guy and not really stable. When he was good he was brilliant in a crazy kind of way. He’d been a captain in World War II and had been left for dead and buried in a mass grave. Then he groaned and was rescued. I think it affected him all his life, but a brilliant, substantial artist, who gets linked into the Kitchen Sink movement of the 1950s.

But he would go out and get totally pissed in the Red Lion pub, come back and sometimes slag students off until they were in tears. How savage can you be about someone’s work? It was almost like bohemian Soho in the late ’50s!

But my time used to get chopped and changed about – mind games is what it’s called. I always used to get that. And inevitably there would come a term in which I just didn’t get any hours and didn’t get called and the red bills would be coming in. I’d phone up and they’d say, ‘Oh, hasn’t so and so sent you any time?’ And they’d send me round to speak to various members of staff – the dance, if you know what I mean? It used to be so petty, bitchy and bitty. One or two lecturers say that it is still like it. Interdepartmental rivalry it is called now! TF

See Part 3 of our interview with Colin read more about his work, ambitions and reflections on life as an artist.

Part 1 can be found here: Part 1

Part 3 can be found here: Part 3