In Part 3 Colin explains what happened after he left The Slade and found fame as a leading light of the British Pop Art movement. In the final part of our interview, Colin talks about his more recent work and muses on what it means to live as an artist.

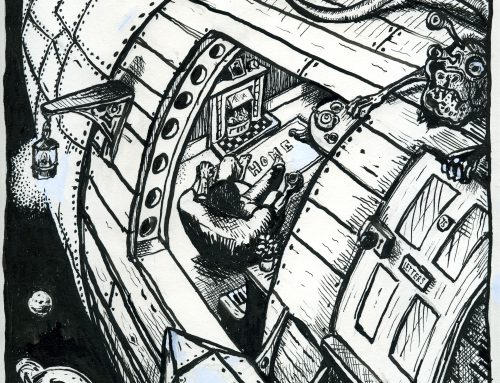

Guard Dog On A Missile Base by Colin Self 1965

Living as an Artist

I am patently aware that if I can’t be creative there’s not a lot else I want to do. I think in the ’70s I would have like to have known manipulative therapy. I thought that might be a good one, but you don’t know who your clients would be, so it was just a dream.

The other thing I did, slightly, was rummage and find bits of scrap metal and stuff. I am like a ferret down a hole in life and love rummaging, I love objects and things and seeing things in things – it’s almost the way I see. I used to find myself taking bits of scrap metal in, but I’d be hopeless at making a living out of it, I patently know that. I’m talking about an extension of art.

My other half, Jess, sometimes does car-boot sales and I go to some of them, which has changed me a lot. I used to be tunnel-visioned and into my art and not make eye contact with people. I’m quite an inward, shy person, I really am, and I think I need to be an artist to say what I feel. Having said that I will look at you! But I know how to fail the interview – I would do it every time. I think they must lose a lot of good people in interviews.

When I started going out with Jess I’d sit in the van and draw people. I must have done that for two years or more and if Jess wanted a wee or anything she’d say ‘Just look after the stall,’ and I’d be terrified. I’d be standing on the bumper thinking ‘Where the hell is she? Someone is going to ask me about something soon.’

It must have been about two years before a lady did come up and ask me how much something was. I think I said ‘30 pence,’ and she said ‘I’ll give you 25,’ and I said, ‘yeah!’ I’d actually made a sale! I thought, ‘Bloody hell, how did that happen,’ then within three minutes I made another one. It had been two years and suddenly I’d done two. I learnt a lot because Jess is much more open and gregarious.

On the other hand, I find no anguish doing a spontaneous talk for an hour and a half to a gallery for 300 people. I can do that. But I’m like a jazz saxophonist, I’ll just blow freeform. Jazz players wear shades so they’ve got this blockage between them and who it is for, but if I looked up and I saw somebody like Jess in the audience then the rest of it would be for Jess because I would have locked onto her and it would weave that way, so I look at the floor much like I’ve been doing in this interview.

I never know what comes next. You might get my inner theories and my hopes and dreams and aspirations, maybe jokes, funny things or wacky stories about well-know artist that I’ve know. They just come out. I get nerves. I’d get three weeks where secretly, if I was picking flowers or digging the garden or mowing the lawn it’s just going over and over in my head. Then, suddenly, I’d get a good idea and think, ‘I’ll lock that away.

Maybe the stories come out and maybe they don’t but it’s like you are creating and revising, constantly. In the middle of the night you wake up and it’s just happening.

If the fee is a hundred quid then it’s patently not worth it but you are doing it for another reason. I suppose racing drivers and athletes do it – they run the race for weeks; they know the course, and what could happen and who could make a break and when. It’s like the creative equivalent of that. So when you actually do it for real, it is a relief.

Show and Exhibitions

On average I’ve been in a group show every ten weeks for 33 years now and it’s unpaid. It’s like this unwritten thing. It is something like 150 shows and its all stress. First you are waiting for the frames, and then you are driving there and it is petrol and you don’t want to do it.

I wonder how many artists there are in Europe or Britain. There are all those art schools with students coming out and every one could potentially become an artist. If you think of how many people who are still living and have been to art school in Britain, it’s got to be millions. That’s a lot of energy and it’s all just happening for free.

So there has to be something wrong somewhere if after ten years there is maybe only one percent of the college intake actually still hard at it. It’s quite unbelievable. How come it’s expected to just be done for free? And MPs on their summer breaks, I bet there aren’t many of them who went to Bosnia or Kurdistan. You know they’ve all gone somewhere tropical, sunny and posh-deluxe. What hypocrisy.

And there is so much corruption in art as well. The freebie trip for the bureaucrats: ‘Darling, I simply had to see the Henri Matisse in New York.’ I’ve been trying to get on with a leading gallery director who has ignored me in the street over the last ten years. Now I’ve had a show at the Tate she’s started ringing me up. But I’ve had my mouth open ready to say hello to her many times.

Recently I was in London negotiating for my Tate show. It was the first autumn after my son had died and I was feeling grim. My son had been to London for two periods of two months, just walking the streets and living rough and he didn’t tell me. It was my first solo trip since then, I was walking the pavement in his shoes and I couldn’t handle it at all.

I was at the Tate waiting for the assistant keeper of the modern collection to come out and see me at the whirly door, but by some coincidence, the Norwich gallery director had caught the same train down and was also waiting for someone in the Tate, but near the desk the other side of the foyer.

And the gallery director still had her nose in the air. And I just thought ‘Fuck you! You could say hello.’ I was negotiating a major Tate show and she chose to totally ignore me. But now the Tate show has happened and had major reviews in the Times and the Observer it has reached the point where the Norwich art set can’t ignore me. That’s gone on for 16 years but it’s like water off a ducks back because I am quite tough. But my punishment hasn’t been as bad as Warhol had, for example. He was certainly victimised but in a big city way. Then everyone felt sorry after he died.

I had a big show of 250 drawings, collages, paintings and sculptures at the ICA in 1986, and then I’ve had the more prestigious one at the Tate in two rooms, which was multimedia and had 59 works in it. I’ve spent the last five years negotiating a major purchase with them.

There’s one on now at the Imperial War Museum, Angela Wake, contemporary work from the museum’s collection. There’s one at the Santa Barbara Museum of art California, 20th Century Figurative Art. London, the independent Gallery who’s a guy called Robin Hardy and he has got the back room of a very trendy, lovely shop on Clifford Street called Squire. The guy designs shirts for rock groups like Blur.

He loves his ’60s stuff. He’s actually got one of the crazy, futuristic sofas that were in Barbarella. That show is called ‘In Glorious Black and White’ and I’ve got two prints in there. Then there was one in June on Cork Street called England’s Glory, which was on for a week when the Euro 96 competition was on.

The old Self household on Greenborough Road

Primal Vision

In the war my dad rag-rolled the bedroom walls with two different colours of paint and when I was a kid and it was getting dark, I’d look at the patterns and see this leaping horse on the wall and there would be another little horse inside its tummy. I’d think ‘Why is there a little horse inside a mother horse?’ The next day it just wouldn’t be there, but I’ve named this kind of thing Primal Vision. It’s a bit like the primal scream and all that Californian ’60s psychology.

I am trying to build pictures up around that initial flash of whatever it was I saw in something. So, for example, behind the hospital years ago I found some hardboard that had obviously been ripped off of a wall somewhere and dumped ready to burn. It was painted black at the top with a sandy kind of cream colour on the bottom, and obviously came from a two tone wall. When I saw it I instantly thought that it could be a desert and the night. I’d built that picture up with pyramids and camels, working around the original Primal Vision. I’m working on a lot of ideas like that.

I’ve also been weaving in what I call people’s art. I’m not saying people’s art is necessarily great – there are more boring folk songs written by the people, than there are good ones, and likewise with trademarks and matchbox labels and images that become folk artistic icons.

I’m also building up some sculptures and trying to work in bronze as well, but making smallish things. And it’s almost like I don’t care how long they take. I suppose if somebody was composing a novel, they’d be writing, maybe not freeform, but not in a way which would look like it had developed or had a thread. But maybe months or years later, you would actually find that, like doing a jigsaw, they’d slide that whole bit across the table because they’d realize that it actually did fit into the other bit. So I’m kind of working in that way! Not myopically finishing a piece and then hurting myself to finish the next. And there is a lot of work which is actually bearing fruit.

Ambitions and Dreams of Life

I have always wanted to be a great artist or a footballer and I never made it in football. But there was a boy, a bit younger than me, called Tony Woolmer, who actually was an art student at Norwich Art School and played football for Norwich City! I saw his first game and he scored and I thought ‘Bloody Tony’s scored!’ He was a second-division footballer, as it was then, and an art student, but never knew what to do.

I once caught the train back from London with Hugh Curran, the Scottish footballer who played for Norwich before he was transferred to Wolves. He played for Scotland too. We were waiting for a train and it was late because there was snow. He didn’t know me from Adam, but I knew him. He said ‘Do you wanna a cup-a’ tea?’ and bought me a cup. And when he drank his tea he threw the little plastic carton up in the air, went to kick it on the line and missed! I thought, ‘Well, I can do that!’ We shared a carriage all the way back to Norwich and it was freezing. And his one joke all the way back was if it get’s any bloody colder we’ll wake up dead. I didn’t get the joke for about a year.

But Hugh thought Tony Woolmer was weird because he was an art student. Can you imagine a footballer thinking another footballer was weird because he was an artist? But if I speak to Tony Woolmer now he says he actually wanted to be a footballer, a great artist and a great rock and roll guitarist – he wanted the whole thing! But I am talking beyond academics; I’m talking ambitions and dreams of life.

Michael Cooper: Blinds & Shutters, Edited by Brian Roylance

During our interview, Colin produced his copy of Blinds & Shutters, a limited edition book of photographs taken by the late Michael Cooper. Colin talks through some of the images and his memories of the time. TF

Blinds & Shutters book cover

Michael Cooper was a great photographer and a lovely guy. I suppose you could say he was an East End Jewish boy, as Keith Richard writes in the front. Michael literally walked around with a camera around his neck and took all the photographs of the Beatles and the Stones. This guy used to hang out with all of them. He must have shot over 40,000 photographs and finally somebody got his pictures together. I’ve got four pages in the book. I couldn’t believe it when it came out.

I signed over a 1000 and got two of these books, one that Francis Bacon signed and one that Andy Warhol signed. Andy Warhol signed 90 copies. Brian Roylance who put this book together, came here with a tape recorder, we spent a day jawing and it all came out in this book. He told me he took a tape recorder to interview Francis Bacon but Bacon said ‘I’m not talking into that thing, but give me a week and I’ll write you something.’ Brian went away and thought, ‘Will he?’ Sure enough the letter came and it just said this:

‘When Michael Cooper was working in the ’60s, it was a much more exhilarating and productive period than now. More like the ’20s. There was exploration and excitement in all the arts and a feeling that something could happen. This feeling had nothing to do with value for money, as now. Francis Bacon.’

Isn’t that great? And he’s right, value for money was all you got in the ’80s. What’s it worth?

Bacon was nice and rated me as an artist. He came across the room with a bottle of champagne and said ‘Someone told me you’re Colin Self, how do you do?’ and we drank the bottle. He was unbelievable – crazy.

Bacon’s hands were beautiful for a big bloke. I mean, my hands aren’t totally butch male; but I once met a Scottish girl who said ‘Och, you’ve got nice hands, normally guys have got grotty hands.’ But Bacon’s hands! And if you put your arm around him he was big – like a fucking barrel, and totally pissed. He was so pissed it was like everyone else had their feet on the floor and he was on a boat all evening.

The stories! He started getting into a conversation with the bloke who ran the Colony Room who I think had originally moved to London in the notorious ’40s or ’50s. “I’ve never heard any other guys get into that sort of rap. But, my God, what an education he was. He was just outrageous and he swore all the time, more than your average sailor.

There’s a picture of one of my ‘nuclear’ sculptures, and Terry Southern, who wrote Dr Strangelove and apparently did the original script for Easy Rider. Terry bought that sculpture after he saw it in Robert Fraser’s gallery, so that’s him with his new acquisition.

I was miserable when Michael Cooper took this picture because the Rolling Stones were in his office smoking joints and were coming out of the door every now and then and sniggering, doing all this putting on stuff as if to say ‘Who the hell is he?’ I just folded my arms and hated it because they were taking the piss. But they were nice afterwards.

There’s a picture of Robert Fraser who was my dealer. He was one of the first people to die of AIDS in Britain. The poor bloke had just started to make a comeback.

That’s one of them building the set for the cover of the Sgt. Pepper’s photo session. Michael has his boy, Adam, in the shot. Doesn’t Paul McCartney look like he wants to ding Adam over the head? That’s Peter Blake with his picture. He left spaces blank for the Beatles to sign it but they wouldn’t.

There are pictures of Peter Blake, John Dunbar, Keith Richard – he had one of my Guard Dog drawings. There’s Bill Wyman. Remember how he played his bass guitar straight up, while chewing gum? That’s Anita Pallenberg, Eric Clapton, Marianne Faithful and Mick Jagger and his boy.

There’s one of John Lennon and Yoko. I never met John Lennon or Andy Warhol either because I was always macho, like a boxer, and it was like a part of me thought I’d better not meet them and make a fool of myself. But we probably would have got on.

But I used to feel like a really country cousin. I thought ‘I’m just not sophisticated enough for these people; I’m not hip to it.’ But I can see from this book that Michael had his problems too. But when I was with him I’d always get lost for words and think, ‘Oh dear, I’m just not up to these people’s mark.’

I knew Jim Dine a bit then. He wasn’t quite in your face but he wouldn’t be backwards about coming forwards. He was sociable. He was great then, but he’s very deeply into his own thing now.

The only time I saw Michael happy was when he said ‘I’m just back from Belgium, I’ve been photographing Rene Magritte!’ I know this is clichéd, but I could have gone across and met Magritte. And I bet you could have rung his bell and he’d have been there. He was lovely. I once saw two highland chairs made out of deer in Portobello Road. The antlers were the back of the chair, the chair legs were the legs of the deer and the seat was the hide. And I remember saying to Christopher Lurgen, ‘I think I should buy them and take them to Rene Magritte.’ TF

Part 1 of the Colin Self interview can be found here: Part 1

Part 2 of the Colin Self interview can be found here: Part 2