The United Nations Development Programme is committed to reducing poverty, championing human rights, offering support to nations in the event of natural disasters and helping struggling governments run their affairs. After 37 years working for the UNDP as resident representative and resident coordinator, Frederick Lyons provides an insight into the activities of one of the world’s most influential organisations.

Frederick Lyons, June 2011. Photo by TF

“I think the most basic one is trusting the individual – having respect for self-reliance,” concludes Frederick Lyons, reflecting on the lessons he has learnt during his long career working for the UN Development Programme. “So much of what I have seen has been about people struggling to make a living and I’ve a lot of respect for that. And so much of our work has involved encouraging governments to show respect for people and individuals, economically as well as in terms of their human rights.

“In a profound way, all good governance has to be based on a respect for people and individuals. The tragedy, and the reason there is so much work for us to do still, is that governments are not very good at respecting their voting public.”

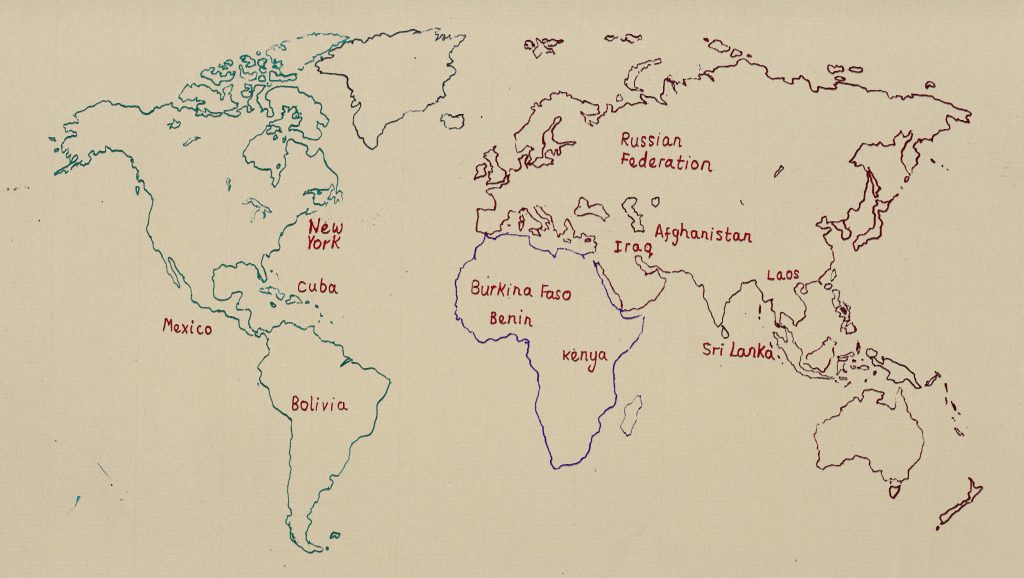

Frederick began working for the UNDP in December 1971, staying with the organisation until ill health forced him to retire in March 2008, just short of the UN mandatory retirement age. By then he had lived and worked in 13 different countries, spending approximately three years in each UNDP duty station. For much of the first 15 years he was the deputy resident representative in countries such as Cuba and Burkina Faso, but from 1987 onwards he took on the role of resident representative and resident coordinator and found himself stationed in a diverse range of countries including Benin, USA, Mexico, Kenya, Russian Federation, Iran, Afghanistan and Sri Lanka.

He met his wife, Robyn, early on in his career and the couple became parents to two girls. Thereafter, whenever it was time to start a new job, the whole family had to move. Frederick admits it was an upheaval, but insists that everyone adapted well to the situation.

“It was a lot of pressure on Robyn and the children. Once or twice, when I announced we were moving the children said ‘No, not again, we refuse. We will never make friends again.’ I think they found it quite difficult at times, but it is striking how adaptable and flexible people are. They always settled in pretty well, I think, and adapted. We were lucky because I had a long-term, five-year assignment in Kenya, which coincided with the children’s secondary schooling, so that worked very well.

“We spent an average of three years in each duty station, but sometimes it varied. We were in New York twice; four-and-a-half years the first time and two years the second, and I was in Afghanistan for just one year because I fell seriously ill.

“For some assignments headquarters are looking for somebody with a very particular specialty to fill a position, so they will make contact and ask if you would like to be considered. They are also constantly sending out advertisements for positions which you can apply for, whether it’s for a resident representative in Azerbaijan or in Latin America; but you have to spend a minimum time in a duty station before you can start applying for new positions.

“When you get a new assignment you are given a moving date and have a few months to prepare. The UN office helps organise and move your belongings and personal effects. A removal firm comes to your house on a given day, puts it all in boxes and, with a sinking heart, you watch everything leave on a truck, wondering if you will ever see it again!

“On arrival in the new country you are welcomed by the office and put up in a hotel while you start looking for a flat or house. Once we’d found something suitable we’d have the place re-painted before the boxes arrived from West Africa, Mexico or wherever we were before. In the meantime the children would have started going to school and life began.

“There are counties where housing is difficult to find and in those cases the UN holds onto a house for you. Kenya was one and Benin in West Africa was another. Not many countries were like that, although I took my predecessor’s house in Laos.”

A Day in The Life

Although Frederick has had several titles over the course of his working life, for much of it he was a resident coordinator/resident representative for the country in which he was based. He explains what the job was all about on a day-to-day basis.

“The resident coordinator is the representative of the UN secretary general in the country, with greater concern for international politics, human rights and the concerns of the secretary general,” says Frederick. “The resident representative is the representative of the UN Development Programme and is more concerned with the country’s economic and social priorities. These are very formal titles used in the UN environment, but basically you have those two titles when you are number one in the office.

“As a resident coordinator, on a typical day, I might have a meeting with the minister of planning, or foreign affairs, about the organisation of the UN programme in the country. Or I might be getting the staff together to discuss a particular project, see how its preparation were coming along and find out if there were any practical problems in the way.

“Take electoral assistance in Afghanistan, for example. It was a huge programme funded by 180 million dollars. When I arrived in the first week of February 2005, the legislative elections were due to happen on the 5th October, so we had nine months to prepare and fund them, get the electoral programme personnel trained and the programme organised.

“The people we had to train were the Afghan electoral personnel who were going to man the voting booths and manage the logistics and security of the operation. All these things had to be funded and organised.

“I wasn’t the only guy involved in this: there was a team of some 30 people working full-time, 24 hours a day. There were constant questions, problems to be resolved and issues to be discussed with different government ministries and the United Nations Electoral Assistance Division in New York.

“Then there is the business of visiting operations in the field; seeing what’s going on and talking to the governors in different provinces. That might also involve meeting UN specialists working in the field, hearing about what they are doing, whether the programmes are up to scratch, whether they are making good progress as planned or if there are problems. And, my goodness, in places like Afghanistan or Kenya you have problems.

“Another day I might be following up on a humanitarian emergency. That might be a flood or drought in Kenya, or a huge earthquake in Iran, like the one which hit Bam in 2003 while I was there. In such cases we would bring together different arms of the UN and other international donors to support the government. That included working with the embassies and different ministries in responding to the crisis.”

Frederick’s UNDP postings across the globe

Chance and Destiny

The job of resident representative/resident coordinator is clearly a very important one, but it is probably fair to say that few people find themselves in a position to consider such a career. For Frederick, it was his degree course in politics, philosophy and economics at Christ Church College, Oxford, which pointed him in the right direction, although he could easily have ended up doing something closer to home.

“At the time it was the standard Oxford course,” recalls Frederick, “but they have branched out a lot in the last 40 years. My main interest was the economics of transport. Initially it was looking at the economic justifications for building roads instead of, say, improving railways, manufacturing new rolling stock and making transport move faster. There are problems to do with how you cost it, how much you charge the customer and how you set the road versus rail versus air competition in policy terms. These kinds of questions I found interesting.

“In a sense, the course was a bit of a mishmash. You could specialize in political theory, the history of politics, or look at logic and various forms of philosophy in greater detail, but in the third year you had to concentrate on one or two subject areas and take more examinations in those.

“In the penultimate term of our third year we were encouraged to get in touch with potential employers and I remember applying to seven or eight different firms and organisations. At that point I saw myself going into the private sector, so I was interviewed by a number of transport firms and offered a job with, what was then, British Railways. I also did competitive tests – comprising a day of panel interviews, individual interviews and a group environment test around a board table – for Shell and Unilever and was offered a job by Unilever to work in logistics.

“Once I’d been selected they sent me to be interviewed by different parts of their enterprise. Unilever owns Wall’s so I was interviewed by Wall’s in Gloucester, who were responsible for their ice cream production and sausages.

“Food transportation is a major problem. Whether you are an ice cream or sausage firm, you are sending perishable produce, like clockwork, to different parts of the world and are therefore managing a huge logistics operation.

“People had been importing and transporting vast quantities of tea and coffee around the world for quite a long time, but it was a time of rapid expansion, and ice cream is a very good model of that rapid expansion. If you think of ice cream today, you can buy dozens of different brands which are shipped all around Europe in really extraordinarily complex operations.

“I’d have probably gone off in different directions once I’d joined the firm but that, of course, never happened!”

Passport to South America

It’s clear to see how Frederick’s interest in transport logistics would have made him a useful employee for both British Railways and Unilever, but before he came to choosing between the two giants, a third option presented itself.

“Then this completely different topic came up which was international development,” continues Frederick. “I applied to, what was then called, the British Volunteer Programme, which consisted of a number of organisations including Care, Oxfam, VSO and the United Nations Association.

“The aid organisation within the foreign office of the British government provided funding for the BVP to pay for young people and new university graduates to go and work in different parts of the world in different specialties. This took the form of a two year volunteer assignment within one of the participating organisations. In the event of being selected by the United Nations Association, which specialized in placing young people in the UN system, you’d be placed with either UNICEF, the UN Development Programme or another UN organisation.

“I was interviewed by UNA and offered a two year assignment in Bolivia, working in their UN Development Programme office, so I asked British Railways and Unilever if I could delay my start for two years and both companies agreed immediately. Those were very generous times; the job market was in constant expansion and for people with university degrees at the time you had every possible opportunity. It was just wonderful. So I went off to Bolivia and that’s where my CV really starts!

“In Bolivia I was working as an economist, preparing economic development projects with the ministries of the Bolivian government. This involved discussions with the technicians within the ministries as to what shape our assistance should take. So we were working on agricultural, small-scale industrial and very early environment programs.

“Robyn and I are going to visit Bolivia next year, so I’m really look forward to seeing how the country has changed in all those years.”

Sticking With the UNDP

When Frederick’s two-and-a-half year mission in Bolivia came to an end, instead of heading back to the UK to take up a role with British Railways or Unilever, he carried on working for the UNDP, despite the fact that it meant a lifetime of living abroad and moving every few years.

“I got so interested that I just stayed with the UN forever; I just found the work so gripping,” explains Frederick. “Altruism is perhaps putting it too strongly but there was a strong sense that we were helping people improve their conditions. A lot of our programmes were poverty reduction programmes, so we were constantly visiting communities, towns and villages, talking to people and seeing how we could help under widely differing conditions. And the widely differing conditions made it so interesting.

“After Bolivia, the UNDP offered me a junior job in the office in Vientiane, capital of Laos, and I spent four-and-a-half years there. It was absolutely fascinating. A completely different culture and environment, with different interests, needs and priorities, and I found that very stimulating and satisfying. I was working with very interesting people in government institutions and within the UN system itself.”

Adventure tales often feature a seasoned civil servant living in some distant imperial outpost, knowledgeable of the ways of the natives, but still holding onto the values of their home nation. Frederick insists that his experiences differed from the fictional model.

“Those books emphasise the colonial dispensation of the good, strong-jawed British civil servant, going out to help the people of whatever country. My time was distinctly post-colonial, so we were working to the governments’ priorities. One can discuss whether or not these were good and useful priorities, and if they were well elaborated and thought through, but basically we were working in a very different environment.

“It’s an interesting community in the duty stations in that the personnel are extraordinarily culturally varied. In Bolivia the resident representative was a Mexican, his deputy was British, there was an American assistant resident representative, a Dutch agricultural advisor, Columbian food aid advisor, a Venezuelan education expert, plus a Costa Rican and a number of Argentine specialists. So I was working with people from a lot of different backgrounds.”

Frederick also insists that the diversity of national representatives did not cause any particular problems. “In Bolivia, for example, it was politically and culturally a very complex environment, but we had common objectives and, by and large, it worked. It is impressive how people do work together when the objectives are well and clearly set out and people show good will.”

The UNDP Logo – an extension of the basic UN symbol

Defining the UN

Shortly after the First World War, the League of Nations was founded in an attempt to ensure that such a conflict never happened again. The concept was revised in light of World War II, and thus the United Nations was born. Its mission was not only to prevent war, but also to tackle a range of other issues, including economic development, human rights and social progress, so a collection of subsidiary bodies and programmes were created, each focusing on a particular area of action. Frederick explains his understanding of what the UN is all about.

“The UN is not a government, but a structure that has been created by governments in order to look at major political, social, economic problems of member countries. The UN Development Programme was one of the organisations set up within the UN system in order to provide economic and social support to member governments. At the time I joined it had representation offices in about 80 countries, and today that figure is about 135.

“The UNDP is also part of the international aid community, providing funding for government agricultural, educational, social and industrial programmes. In practice, the funding gets added to government programmes in order to enhance their agricultural production, improve water supplies, help them plan their energy requirements, and to train people such as civil servants, teachers and farmers to do some of these things.

“Each country requesting the assistance of the UN is asked to prepare plans for the next four or five years, showing where they wish to incorporate assistance from the UN and other donors, such as Britain and France.

“There is no cast-iron programme that applies to all countries. The principle under which the UN works is that it responds to the priorities of its member countries, and each country will have different priorities at different times, depending on where it is along the development continuum.

“Part of the terms under which the UN was created was that the richer countries would provide support to the poorer member countries, but the UN works in the middle income developing countries just as it does in the least developed countries. It works in Mexico, Chile and South Africa, but also in Laos, Equatorial Guinea and Bhutan – some moderately prosperous countries and some very poor countries. So each one will have very different and specific requirements in terms of its priorities and the response it wants from the UN.

“You have to be sensitive to each country’s attitudes and ways of doing things. I always found that particularly interesting. It is part of the wonder of doing that kind of work.”

Managing the Money

Before practical support of any kind can be offered to a nation, there is the small matter of funding. Once the country’s objectives, or ‘priority programmes’, have been identified and it has specified the help it needs to carry them out, the UNDP steps in with a financial pledge.

“Essentially the UNDP tells member countries that they can count on financial support to the tune of however many tens of millions of dollars over the following two or three years,” explains Frederick. The government states how much money it is putting on the table in order to complete the proposed priority programmes, then, because these programmes are quite sizeable, you usually turn to other interested bilateral donors – like Britain, USA, Germany, Netherlands or Italy – to complete the programmes. So the programmes are almost invariably a complex package of different forms of funding from different sources.”

Understandably, every organisation or country contributing to a UN programme wants to know how their money is being spent, which means that everything has to be carefully recorded.

“The donors are constantly calling us to account but it is all accounted for,” insists Frederick. “For instance, the electoral assistance programme in Afghanistan was accounted for down to the last cent. Every donor receives a financial report and a report on what has been achieved at the end of the financial year. Again, a typical day of mine would often involve meetings with UN agencies, one or two people from the government and a number of donors, to review the progress being made with a particular project. It might be a de-mining programme in Afghanistan or Iran, or an agricultural development or road building programme.”

“We were expected to give an example to the world at large of good, clear, capable administration, so a lot of work is involved. As you prepare the programme, consideration is given to social conditions, issues of poverty and how to reduce it more effectively. For example, you have to decide whether to make the programs employment programmes or focus on capital investment.

“Then, as you develop the programme, you look very, very precisely at the administrative considerations. Can you deliver the programme in a transparent and accountable way? Is it realistic? Are the facts set out clearly? Is the information getting to the UNDP office from the very complex operations on the ground? So there is a lot of administration and sometimes, frankly, it can be a little ponderous, but it is essential.”

Good Governance

One of the major activities undertaken by the UNDP is giving support and guidance to failing governments, often after the fall of a dictatorship.

“Governance is support to governments in every aspect of management,” explains Frederick. “This can involve issues which relate to financial management and planning, but it can also relate to improving the systems and institutions of government. The UNDP is increasingly getting into issues such as the fight against corruption and how to manage it.

“The typical governance programme is the management of an election, but it can involve, as it did in Afghanistan, the rebuilding of parliament. That was not just constructing the building, it was ensuring that the parliamentarians, when they returned to parliament after 20 years of no parliament, had systems and trained staff to support parliamentary operations. For example, the Afghan parliamentary staff were sent to see how the British, French and German parliaments worked. They were trained and now there is a functioning parliament in Kabal.

“Governance can also involve questions of human rights. It might look at how the human rights commission should function in a given country. So you provide training and management support to the human rights commission so it can function, deliver results and be accountable to the broader public.”

The UNDP is also very active in establishing and promoting microfinance projects which help a high number of individuals by providing them with very small sums of money so that they can start a business or solve a problem.

“A microfinance project would often be treated as an element of small-scale poverty reduction at the local level,” explains Frederick. “In a number of countries where we worked, my typical day involved either visiting microfinance projects or working with the government to establish small-scale microfinance activities.

“In Kenya, for instance, we worked with a US foundation called Trickle Up, where we provided very small grants to micro-entrepreneurs. They merely had to outline on a sheet of paper what it was they were planning to do and identify what their contribution to the micro project might be. We would give them a first grant of 50 dollars which they could use to buy equipment or start-up materials for their operation.

“If they were successfully in production, or doing whatever job they had planned to do, they could come back and ask for a second and final grant of 50 dollars a few months later, and these things were surprisingly motivating and successful. So it’s just breaking a tiny bottleneck. What to you or I sounds like a tiny financial obstacle can be inconceivably difficult for the poor to overcome.

“But in Afghanistan, for instance, we were working with BRAC, the Bangladeshi microfinance operation. We were funding BRAC’s support to a number of Afghan organisations; training Afghans to manage microfinance activities. So a lot of work is bringing the best knowhow from other developing countries to work with government and non-governmental organisations.”

The UNDP website home page

Specialist Skills

It’s hardly surprising to see that the UNDP missions Frederick has undertaken over the years have been in areas of the world where there have been major economic, political and social problems. Nevertheless, he eventually found that it was humanitarian issues which interested him most, and became his area of expertise.

“I started in an organisation that was primarily working on straightforward economic development, by the transfer of productivity and production knowhow. Gradually our organisation became increasingly involved in issues relating to governance, humanitarian and human rights issues. Today UNDP staff are involved in gigantic operations in Haiti, Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, and continue to be involved in Timor, Somalia and other operations dating back to the 1990s and early 2000s.

“From Kenya onwards my involvement in humanitarian operations grew and I became something of a specialist. In Russia I was deeply involved in humanitarian issues concerning Chechnya. I went from there to Iran where there was a terrible earthquake in Ban at the end of 2003. From Iran I went to Afghanistan where a lot of the work had a humanitarian context and from there to Sri Lanka, where I was involved in discussions with governments and the Tamil Tigers on humanitarian issues. So that was a growing specialization and I was repeatedly asked to go to those kinds of programmes and countries.”

Being able to speak a number of languages was also a very important skill for Frederick to have in his job. “When I joined the UN my first duty station was Spanish speaking. I spent most of the day speaking and writing Spanish so, even if my Spanish was a bit rudimentary when I joined, I got used to it and learnt fast.

“I had to make speeches in Spanish to the public, civil servants, and sometimes at inaugural events. There were quite a lot of formal events, but sometimes I was talking to villagers about a project, explaining what we were doing or introducing new approaches or technologies.

“From Bolivia I went to Laos and worked exclusively in French, as it was a French speaking country at the time. My mother was French so I really have two mother tongues. But apart from New York, the first Anglophone country I worked in was Kenya.

“A lot of my work was out in the field. On a typical day we’d be up at 5.30 or six o’clock and on the road before breakfast to get to a village 200 kilometres away. Once there, we’d spend the rest of the day with the villagers seeing what they were up to and what they wanted. You’d hear what the problems were, listen to their requests, demands or complaints and try to deal with them together with the project specialists.”

At the other end of the scale, Frederick’s job involved many meetings with politicians and government officials, discussing matters on a more general and administrative level. “If you are dealing with the minister and his or her number two there are political overtones and, quite often, delicate issues to be discussed. Often you are in the ambassador’s office at embassies, discussing the future of a programme or how it is coming along. That ambassadors’ government may have some money invested in the project and very particular views as to how it should be delivered, and what should be happening next.”

Frederick Lyons, June 2011

Thoughts on the World’s People

In his line of work, Frederick has been privileged enough to visit some incredible places and meet many fascinating people. He has also seen hardship, poverty and the tragic consequences of conflict. He reflects on what he has seen over the years, draws a few conclusions and offers some of his fondest memories.

“What always struck me was how desperately hard people work in their communities. Seeing the harshness of life in the farming communities of Mexico, Bolivia, Laos and Kenya often drove me on. I felt those people deserved an easier life, especially the women. It is so hard for them. Often they are bringing up a family as well as having to work in the fields under very harsh conditions.

“I loved working with the fascinating cultures – the extraordinarily rich Aztec and Mayan cultures in Mexico and the Inca in Bolivia. Then there were the strikingly beautiful landscapes. I can remember working with a team of French cartographers who were making maps with UN funding in Northern Laos. We went into villages with them and the villagers put us up in their little huts in the fields high up in the mountains. I remember waking up at dawn in the midst of a poppy field in the mountains above Vang Vieng, some 100 kilometers north of Vientiane. It was just extraordinarily beautiful. And I also recall attending a meeting in Nepal and seeing the sunrise over the Himalayas – just wonderful moments.

“I was almost always in places where there were no hotels. Often there would be a very rudimentary little guest house. In later years there were more hotels, but still quite rudimentary.

“The world has changed in very striking ways. There are more children in education, health conditions have improved, and in most places roads have improved enormously so trade has expanded. I think the message over all is a positive one.

“The news only captures the negative, in a sense. It’s very striking that what you hear about a number of countries accentuates the negative when in fact you are often welcomed and made to feel at home by the people there. They are actually extraordinarily hospitable and you get a completely different sense of what makes a place tick.

“Of course the news isn’t there to focus on how beautiful or fascinating the country is; the news is there to reduce it to a set of fairly comprehensible sound bites. But when you are working in a country you are constantly engaged in trying to grasp how complex things are and the message is completely different when you get into the complexities and subtleties of a given place. And that is true everywhere.

“You need to approach all these places, whether it is your home village, Prague, Bangkok or Moscow, with a sense of humility. These are not things you are going to understand after a bus ride or by the following morning. You have to keep asking yourself questions and approach with humility otherwise, what’s the point? You end up being the arrogant foreigner.”

Giving It Up

There are very few people who display as much enthusiasm and excitement for their job as Frederick Lyons. Only ill health forced him to give it up, but now that he has, it is a chance for his wife to realize a few of her ambitions. When Robyn met Frederick she was a diplomat working for the foreign office in Laos, but had no option but to give up her career so that she could follow her husband as he was posted from one country to another.

“She was fantastic about it and we were together all my professional life,” says Frederick. “She moved around with me for decades so I owe her. When I was sent to Afghanistan, Robin had come back to London to finish a masters degree and got a job in publishing. Things became increasingly problematic for me health wise so I decided I’d better come back too. But it was a tremendously exciting job. It really was wonderful.” TF

See also our interview with artist Tom Young, who is experiencing life in the Middle East. Tom Young: Painting in Lebanon can be found here: Tom Young