Industrial Designer Rick Dickinson made his name working for Sinclair Research Ltd in Cambridge, developing the ZX81, ZX Spectrum, and Sinclair QL home computers and the TV80 flat-screen pocket television. Having launched his own company in 1986, he worked on Sinclair’s innovative Cambridge Z88 laptop computer, and for Acorn and Amstrad. Rick explains what it really means to be an industrial designer, and how a series of fateful decisions led him to become one.

Rick in a rare two-seater Spitfire, owned by Carolyn Grace. There are only two working two-seaters in the world.

“Culturally, as a nation, we are absolutely devoid of any understanding of manufacturing,” reflects Rick Dickinson regretfully. “Yet absolutely every single artifact around you, whether you’re sitting at home, in an office, or walking down the street, had been designed by somebody. Everything has been considered for manufacture by a designer, whether it’s the little plug that goes in the bottom of your phone, the cable that attaches to it or the knob on your door.”

“If you are in another European country, you can be in a little shop in a grotty part of town and get talking to the guy behind the counter and as soon as he hears the word designer he knows exactly what you do and has a pretty good grasp of manufacturing, materials and aesthetics. Obviously the people in industry know it, but maybe there are fewer and fewer people in industry.

“There is such a huge and increasing divide between two fundamental sections of society: those that do it and make it happen and those that buy it. I should say that 99 percent of the people who use the iPod, or whatever fashionable high street, high-volume product it is, have no notion whatsoever of the monumental risk, foresight and investment that has gone into getting that product into their mitts.”

Rick is passionate about his job. At times he describes it as being a nightmare and impossible, but even when he does, it is with a certain kind of fondness. One gets the impression that if it wasn’t a monumental challenge, he’d be doing another job that was.

His name will be forever associated with Sinclair, having worked on the ZX81, ZX Spectrum, Sinclair QL and later the Cambridge Z88 laptop, but for the last 25 years Rick has run his own industrial design business called Dickinson Associates, based in Cambridge. The company specialize in the design of telecommunication devices and medical equipment and have a list of awards too long to list here.

Industrial Roots

Reflecting on how it all started, Rick believes that his interest in design grew from a childhood fascination with vehicles, buildings, bridges and model making.

“I was always interested in drawing stuff, but I wouldn’t draw a tree or a bird, it really was inanimate objects. I certainly had my pet subjects; trains, railway locomotives and aircraft, because my father was an aeronautical engineer. When I was young he worked for Blackburn’s on the Blackburn Buccaneer. It was a low-level navy strike aircraft which operated off of aircraft carriers. It was one of those classic designs from an innovative British company, dating from the Cold War period, so the plane was designed for attacking Russian nuclear battleships. It had to get quite close to its target, so the navy drafted up a specification called Navy Assignment 39 – NA39 for short, which is the code for the Buccaneer. The aircraft had to be able to fly below radar, as close to the speed of sound as possible and drop a nuclear bomb! It had never been done before in design terms and was very difficult.”

“I remember going around the factory and seeing hundreds of drawing boards in the offices. My father was always drawing and sketching as well as making things, so the garage was full of aircraft bits going all the way back to Lancaster bomber parts.”

“Unsurprisingly all his friends were that way inclined as well, so wherever I went there were massive machines and people making incredible things, so I was very heavily influenced.

“I don’t recall any formal design tuition from my parents. I was just forever in the garage making things and trying things out. I think that gave me an innate feel for materials, how things go together and what you can and can’t do.”

“I was working with a wide range of materials. Plastics were coming in and because dad was in the aircraft industry I saw materials that were quite interesting, like polypropylene and nylon, for example. As a child, you are very limited in your access to tools and knowledge of what you can do so everything was trial and error. It was any tool I could get hold of, short of oxycethelene, so it was saws, hammers and chisels. You soon discover that you can’t saw a piece of brass with a wood saw and you start to develop a feeling for that sort of thing.”

“As a child I’d spend a lot of time in Germany, Holland and Switzerland, particularly Christmases and birthdays, because my mother is half Dutch and half German and we’d visit her family, particularly in Germany. Lego had just been launched in Denmark, and I think Germany was probably the first country outside of Denmark where Lego was marketed, years before it came to the UK.”

“A boy who lived upstairs from my grandparents used to bring down a sack full of Lego bricks and empty it on the kitchen floor for us to play with, and I was absolutely hooked. Every birthday and Christmas after that people bought me boxes of Lego and I’d build everything from suspension bridges to spaceships. The traditional Lego bricks were just the square and rectangular format, so you had to be really inventive and imaginative to make something curved with them. And also, a little bit later on, Gerry Anderson came out with Thunderbirds which was, for me, the most amazing thing I had ever seen in my life! It was a designer’s dream. So I’d say this is all part of making things and trying to be creative.”

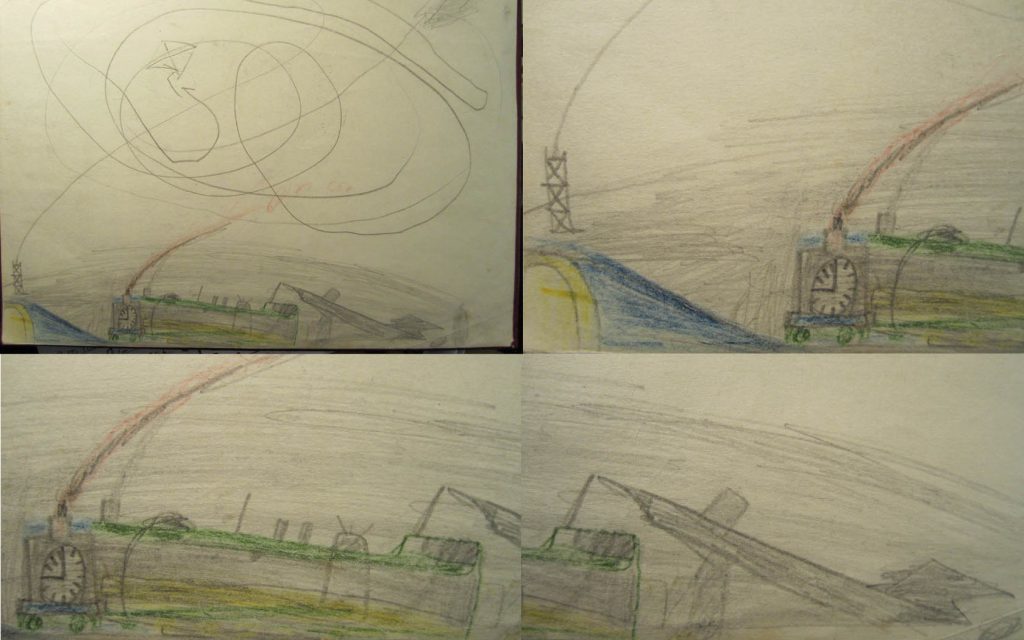

Rick: “I found this scribble in a book given to the family, called ‘Railways the World over’. It was not the done thing to scribble in books and I guess I could barely hold a crayon when I did this. I think the locomotive is pulling a rocket, and I can see there is a rocket launch tower, and I liked tunnels.”

When I Grow Up

As a child, Rick decided he wanted to one day be a train driver and then a lorry driver before considering a career as an artist and a train driver once again. Eventually, though, while still at school, he settled upon the idea of civil engineering, which partially satisfied his interest in structures.

“I remember spending hours looking at photographs of bridges, buildings and dams in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, but when I got into sixth form I started to realized that it probably involved too much maths, which I didn’t have a particular flair for. But even today I love watching new motorways and bridges being built. I could stand there and watch forever. If there is another job I would have liked to have done it would have been civil engineering.”

Aware that civil engineering was perhaps more about making calculations than creative design, Rick decided to pursue a career in architecture, which appealed to his interest in the aesthetic. He made sure that his A-level subjects were appropriate and collected the prospectuses for three colleges running suitable courses. And that is what he might well have ended up doing, if it hadn’t been for a chance meeting one day.

“It was my last day in the sixth form,” remembers Rick, “and I just happened to be walking through the art room when my teacher asked me what I was going to do. I told him it was architecture and he, said ‘I’m surprised. I thought you’d be doing industrial design.”

I said “What’s that?”

“He said ‘Well, it’s just up your street. It’s designing everything from forks and knives to forklift trucks. You make drawings, models, prototypes and then it all goes into production. It involves everything you are good at and like.”

And by an amazing coincidence he had a yellow-looking prospectus from what was then Leeds Polytechnic. He flicked through it and that was it – that was the turning point.

“I discovered there were a number of three-year industrial design degree courses, a few of which were geared towards things like furniture design and 3D design. I can’t remember why I approached Newcastle, but probably because I had quite a few drinking buddies at the university!

“They said they’d give me a place but by then, of course, my qualifications weren’t ideally suited, so I had the option of doing another year of A-levels and taking different subjects, or a year’s arts foundation course, which is what I chose because I’d really had enough of school.”

“Newcastle Polytechnic also said they liked people to go to Carlisle for their foundation but when I got in contact with Carlisle I discovered that I wouldn’t be awarded a grant and would have to pay for it myself. Because dad worked for Blackburn’s aircraft company, we lived in a village in East Yorkshire, so I had a Local Education Authority grant that allowed me to do the foundation course at either Hull or Grimsby technical college, and I chose the latter. I thought it was time I left home so took the paddle steamer across the river Humber, went to the tech and lived in Cleethorpes by the sea, which was absolutely brilliant.”

“This was me at about age 15. I built all of these boats from scratch. The Russian destroyer is balsa wood. I copied it from photos. The boat I’m holding was a Fairy Marine Swordsman, and to the right is a Fairy Marine Huntsman – both built from plans using traditional boat building techniques, with keels, bulkheads, spars. I used marine ply, Cascamite glue, and applied lots of coats of paint, each rubbed down between coats. I fitted internal combustion engines and Radio controls in each. The boat on the left is one I built from a photo without plans. I made different designs and eventually used the wooden hull construction method as a pattern to make a fibreglass mould, from which I could then make as many hulls as I liked, in ever decreasing skin thicknesses and weight. I learned about keeping the centre of gravity as low as possible by having the engine very deep down; laminating the engine mounting directly into the fibreglass, increasing the thickness of the fibreglass only where extra strength was needed, but graduating the increase gently from the thinner sections.”

Foundation for the Future

The idea of an arts foundation course is to provide the student with a broad grounding in a range of creative subjects, thereby preparing them for a degree or vocational diploma. Because Rick already knew that it was industrial design he was intending to do, he chose to boost his experience in relevant subject areas during his foundation.

“We had choices but I’m not sure if you could have done everything,” Rick says. “I had an interest in Cine film and stills photography by then but I didn’t bother with photography because I did it at home. Then, instead of pottery, I did sculpture. Sculpture was fantastic because I’m better at replicating a shape in 3D than I would be illustrating it or painting it, so I learnt a lot of new techniques, like plaster casting from a clay model.”

“I also did fine art, which was life drawing and still life painting. I was familiar with watercolour and gouache just from playing around with it at home but I discovered oils on the course. Oil on canvas was something else – my word! What a breakthrough! Fabulous stuff.”

“On the course I met people who really were good at painting, but I was never especially good at drawing and painting and really just saw it as a means to an end. Things are not very clear in your head so the next stage is pen and paper. Then the utter reality, of course, is the physical world. Not until you get into that do you really start to learn what the true situation is, so drawing was just a means of getting to that end of making something.”

Rick’s education in manufacturing products and manipulating materials was not simply limited to what he learnt on his course. By the time his foundation course had started, his father had moved from aeronautical engineering into structural engineering and was pioneering new ways of using composite materials.

“He ran his own business,” says Rick. “A one-stop-shop is what you would call it these days, but that term hadn’t been invented then. He’d get the business, design the product, make it, install it and service it. They dealt with huge projects for the National Coal Board, working down coal mines, and they went to Baghdad to work on their sewers. I think they designed and built Europe’s tallest freestanding plastic flue, which was about 200 feet tall and situated in Iceland. So from him I was learning all about making moulds with fiberglass, de-moulding and so on.”

Rick: “My Father was educated at Oatlands and then Uppingham, after which he went to Loughborough to study engineering. After the war he joined the Blackburn aircraft company at Brough, where he designed the supersonic wind tunnel for the Buccaneer, and various parts of the Buccaneer, including cockpit sections. The wind tunnel relied on compressed air and it took an entire morning to pump up sufficient pressure for a couple of minutes of supersonic whoosh – which you could hear ten miles away each lunchtime. His Father was the founder, along with his brother, of the Public Benefit Boot and Shoe Company. They started making workers boots in their front room in Bramley near Leeds, then expanded and expanded by developing new methods, tools and mechanization, and introducing new materials from around the world. They eventually created the first ‘chain store’ with over 300 stores. There are Benefit buildings all around the country; some have preservation orders – like the Leeds factory in the photo, which became their HQ. Clearly the roots of invention go back a while.”

Design for Industry

After completing his foundation course, Rick reapplied to Newcastle Polytechnic, only to find that the old three year course had been dramatically altered and renamed. Nevertheless, having already completed a foundation year just to get a place, he was not about to let the changes put him off.

“The tutors had reengineered the course based on a lot of research with industry figures,” explains Rick, “principally asking them what skill base they needed from students. The new course included a couple of one-term work-placements in industry, which you could extend over the summer holidays. They also added another year, called it a sandwich course and changed the name from Industrial Design to Design for Industry, which was a very precise and clear title.”

Rick’s course proved to be a successful attempt to marry design education with the needs of industry and was subsequently mimicked by other technical colleges. Clearly it must have been important to the college that the first year of the newly-structured course got results, so Rick and his fellow students found that they were pushed very hard.

“We were the guinea pigs,” insists Rick. “It was incredibly intensive and the hours were monstrous. There were two days in the week where you were still in the studio at seven or eight o’ clock at night. It was also very, very wide ranging. For example, there was a complimentary studies aspect which took us through all sorts of things like accounting, marketing and law, which was quite interesting.”

“We received many visits from outside representatives from all sorts of businesses. So, for example, the marketing director from General Motors came in, as did some people who were helping in developing countries, finding solutions to problems using design as a tool. Then there were more obvious guests, like designers who would go through their work, talk about what they did and answer questions. Quite often they would stay for several days and mingle with the students in the workshop or studios.”

“The student catchment was different to normal courses at the time. At one end of the spectrum you had mature students who had come from manufacturing backgrounds and had run their own businesses. One guy was an industrial artist, so he could do a drawing of a watch and you’d think it was a photograph. Then you had guys straight from sixth form at private schools. The students came from all over the country so we really were quite a mixed bunch, but we were also highly competitive.”

Rick appreciating the design of a convertible! Rick: “This happens to be my 1969 Triumph TR6 – which I saved up for in my first two years at Sinclair. It is still running well.”

Practical Matters

Rick’s course was characterised by its strong bias towards volume production, thereby gearing its students for typical industrial manufacturing jobs. It also made sure that the students got first-hand experience using materials, as Rick explains. “It was very heavy on practical work, so we had to learn about every imaginable material and method of working that material. So, for example, we’d go through a course learning everything about wood; relative humidity and why you would choose one wood over another, different ways of converting wood into form, the relevant machinery for working wood, and why you would use one machine over another.

“We did the same with metal, plastic and ceramics. Ceramics took us into the pottery department where we learnt to throw pots on a wheel. We learnt about slip casting, how to make glazes and glaze transfers. I remember designing a range of storage jars of varying heights and constant section. I made my patterns out of jelutong – a patternmaker’s timber which is very stable but probably quite rare now. I made a plaster mould from that and from the plaster mould I slip cast. I made my own coloured slip so the pigment was in the clay itself rather something applied to it afterwards with a glaze, and then I used a clear glaze.”

“I remember designing transfers and screen printing them. On the course we did textiles as well so we used our textiles knowledge to screen-print transfers before firing the jars in the kiln.

We even did jewellery. I designed a set of cutlery, made the blades out of steel and chrome plated them and the handles from ceramics. Years later I remember seeing in a shop cutlery with ceramic handles!”

“Obviously we were never going to come out with works of art or something that was beautifully, easily or perfectly manufactured, but it was about understanding materials and learning where the problems lay. I can’t think of any material that we didn’t use, so it was incredibly wide ranging.”

“Each design task or project we were set included a conceptualization phase where you’d think about different design ideas, maybe an illustration phase, and certainly a model-making phase. Model making was very much on the agenda, but luckily I was pretty good at it because I always made things. I guess I was the top at model making so I really milked it. I’d go to town on making models because they had such an impact compared to even a fabulous illustration, which is still just one carefully chosen view of a design that doesn’t tell you much about it. Conversely, there are no hiding places with a model. You can pick it up, walk around and choose your view.”

“For our designing they would set us pretty difficult design tasks where it wasn’t quite clear what the point was. I suppose it was a bit like being in the army or the forces, where you can’t see the point of being told to iron your shirt for the fifty-second time that evening! It was a mind game and never done in straight language. It never made clear enough sense so you always felt there was another agenda and there was a lot of student unrest. A few people dropped out and a few were asked to leave.”

“But with time you realized that they were teaching you to observe or test how good you were at reading a brief and picking out the important things. Whenever a project was set, part of the early appraising would be an analysis and you went away and produced a report on what you thought the question was!”

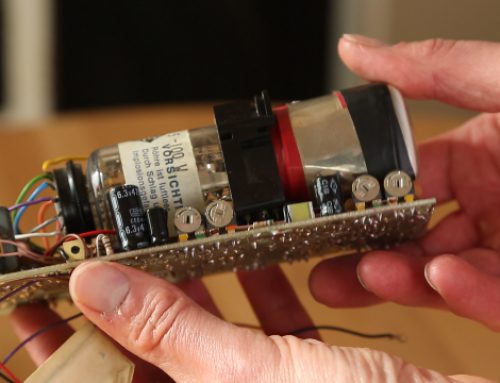

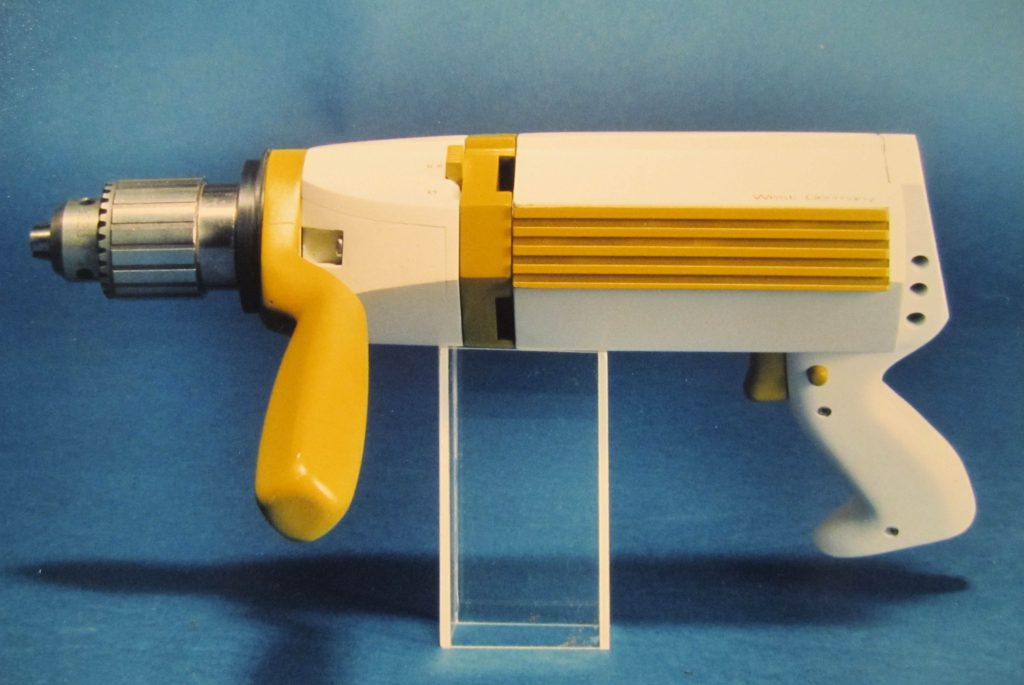

A drill model Rick made on his Design for Industry course (see main text below). It was featured in Design magazine. Rick: “The electric drill was more of an ergonomic exercise – I discovered that a carpenters plane handle (a tool I was very familiar with), makes a great drill handle as it is held in a similar way. The other (swivel) handle was modelled on a chisel handle for the same reasons. The yellowish colour is actually lime green.”

To Conform or Not To Conform

Although Rick enjoyed much of his course, presentation was one facet he intensely disliked. For him, dressing up quickly-sketched ideas and notes, by professionally arranging and mounting them, was simply a wasteful use of time and energy.

“If you imagine there are 100 hours from picking up your brief to finishing the job and showing it to someone, 25 percent of that went into creating the presentation material,” explains Rick.

“Depending on the problem or question that was been asked, there are different ways of going about showing someone what you think the answer is, but we had to show a clear line of thinking and progression. In principle that is OK, but the life of a sketched idea is seconds and we would have to go back over our scruffy little sketches making them look pretty and presentable at every stage. Then it would be hours mounting things onto boards and titling everything up. And it was all bullshit really, because it wasn’t about content. To me, design is all about finding design and engineering solutions; how you’ve written you name on it really doesn’t matter.”

“I guess I played games where I would conform to the requirements of the set brief but didn’t do it in an especially presentable way. I remember having to illustrate a journey from somewhere to somewhere else using between six and eight images. I chose my character to be Dennis the Menace and did sketches with Dennis and Gnasher going for a walk from some place to some other place. We had to present everything in front of the class and everyone had a good laugh at mine. Now, I’m no illustrator – I couldn’t illustrate a children’s book, for example – that’s not what designers do, necessarily. So they asked me to re-do the work and I just re-did it exactly the same way, but presented and mounted it beautifully. They were happy with that, but the content was the same! So I got really cheesed off with all that.”

“Looking back I can see the point, but at the time I couldn’t see the point of half the stuff they were doing and at the end of my first year I was actually threatened with expulsion. I felt I needed to think about my future so over the summer I went to North America for a couple of months, got a Greyhound coach pass and travelled. The head of the course, Alan Burke, had set us a project for the holidays which was to take a sketch book wherever we went. He said ‘I want to see no less than 50 pages of sketches,’ so I bought a little Daler Sketch pad, probably about A5 size, and took that with me.

“I did about 12,000 miles around Canada, Alaska and the US, and I just filled it. When term started in the second year and I presented this and they thought it was fantastic. Something must have happened there because I thought ‘What are my options? I can’t leave because what am I going to do if I leave?’ Often the reason people stay with what they’re doing is because they can’t find a better alternative. So I stuck it and thought ‘OK, I’ll do what they want and what the curriculum is requiring; I’ll pay lip service to it and do it at least to an adequate standard, but then, on top of that, I’m going to do what I want to do.’ So I doubled my work load and that’s how I went forward – I did what they wanted but also what I wanted on top of that. I thought ‘They can’t criticise me for that.’

“I had my personal review at the end of that term and they were very pleased. Bear in mind that just before the summer I been told that if I didn’t pull my socks up I’d be off the course. I must have somehow figured it out – the penny had dropped – and I got into a good routine. Once I’d got that momentum going I just maintained it, especially in the final year which was critical.”

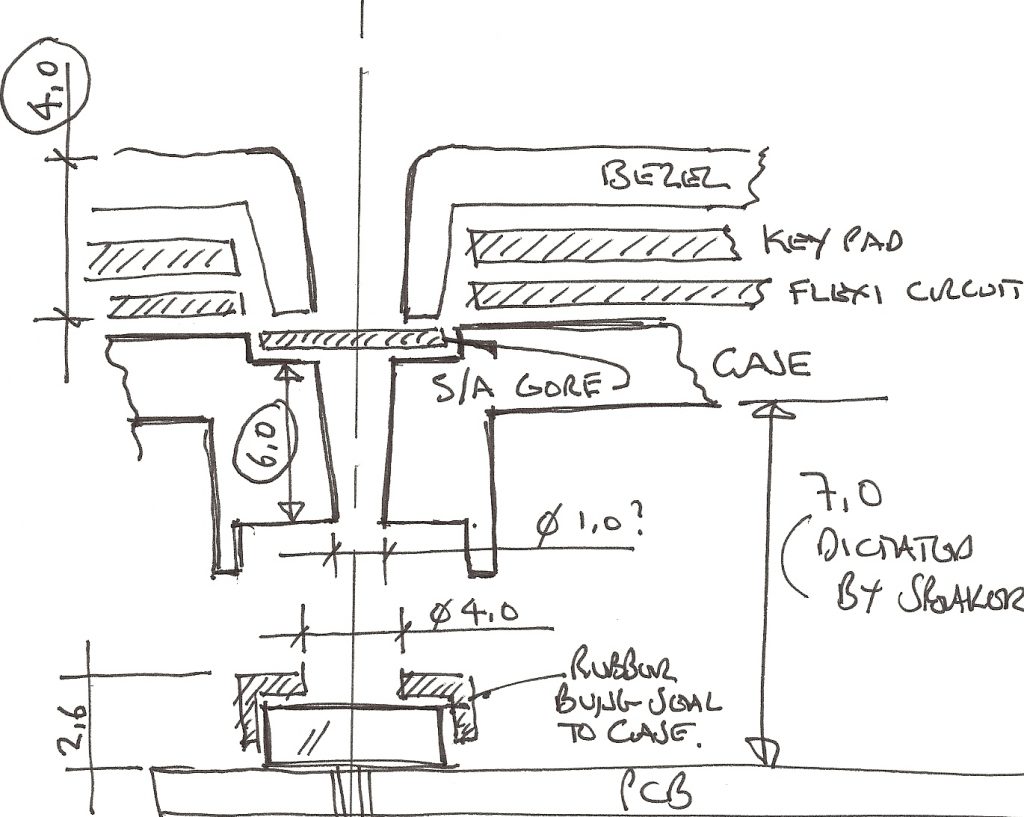

An example of one of Ricks recent idea sketches. Rick: “Interestingly this is a sketch to work out how to assemble a microphone in a handset so it will work and also be water proof. This is a sectional sketch and the passageway, or hole, is only 1mm in diameter. The tapering lines illustrate the effect of ‘draft’.”

Work Placements

The last terms of both the second and third years of Rick’s Design for Industry course were set aside for the students to leave the college and take on a design-related work placement with a private company. Over the years, the college had compiled a directory of friendly manufacturers, mostly local to the college but some as far afield as London.

“My first placement was with a company called Kesslers based in Stratford, London, down by the canal,” Rick recalls. The chief designer there was Alan Kersh and I think Alan might have been at college with our tutor John Elliott, who was in charge of student placements. The list of placements was certainly partly based on a social network.”

“John Elliott was our youngest tutor but had worked for Bill Moggridge Associates who were at the time, and possibly still are, the UK’s leading industrial design consultancy. Bill Moggridge himself was actually our external assessor for our final show. John was unusual in the sense that he was very close to our age but still had industrial experience, which was so valuable to the students.”

“Kesslers specialized in point of sale displays. So they would have clients like Citizen Watches, W.D. & H.O. Wills and a whole range of pretty upmarket cosmetics companies. They were a one-stop-shop, so they would get the business in, design the merchandisers and the advertising at the point of sale and make and install them. So if there was a newsagent with W.D. & H.O. Wills cigarette dispenser behind the counter, it was probably designed and made by Kesslers in Stratford. They had every manufacturing process known to man under one roof, so that was quite interesting.”

“I didn’t particularly like the placement because it wasn’t really my scene – nothing to do with them, it just didn’t fit me – but I learnt a lot nonetheless. I learnt about graphic design and lettering, for example, and how one letter is placed after another and how critical that actually is.”

Rick’s second work placement, in the summer term of his third year, was a very different matter, eventually proving instrumental in his career. But at first, it all looked as though things were not going to work out for the good.”

“There’s so much of what seems to be luck in life,” laughs Rick “I was the last to get a placement in the third year because I’d had such a disappointment with my Kessler placement. When I heard about some of the placements that other people had done I thought ‘Gosh! That would have suited me much more.’ It was just luck of the draw, but I was more particular the second time, as long as the situation would allow.”

“John Elliott was pulling his hair out, racking his brains to find something for me. I remember I was in the spray booth painting a model of an electric drill. Apparently I did really well with this model and a photograph of it ended up in the Design magazine. The drill was white with lime green and I was desperately trying to get the lime green colour just right. I tended to live in the spray booth so if they wanted to find me they knew to look down in the workshop.”

“So John came to find me and said ‘Rick, I’ve got this company, how do you fancy this? I’ve just been talking to John Pemberton; he’s the industrial designer at Sinclair. You know, they do all the calculators?’ I though ‘Oh my God!’ I couldn’t believe it. Everyone had a scrapbook of some sort and mine was full of Sinclair adverts for the Sovereign and Executive calculators, so it was a match made in Heaven. I went down and had an interview just to formalize it at the mill in St Ives. I graduated in 1979, so I suppose that must have been ’77. I remember they already had the TV1A pocket TV on sale and were getting the TV1B into production.”

“I was interviewed by John Pemberton who was a celebrated product designer by that time and had earned many design awards. John trained at the Royal College of Art and, interestingly enough, his external assessor was Barnes Wallace!”

“I can’t remember if John introduced me to Clive at that point, but it was a fairly low-key affair for the company because they employed a couple of hundred people at that time. So I started work as John’s assistant at the beginning of the summer term, stayed on all through the summer, had a fantastic time, drawing and making models. It was just like being back at college or at home in the garage and John and I were so similar.”

Enderby’s Mill as it is today.

Uncertain Times

Eventually Rick graduated from the Design for Industry course with a first class honours degree, and was understandably thrilled. Having gained the top mark from such an industry-specific course, Rick could have been forgiven for expecting to find plenty of work offers waiting for him after graduation but, surprisingly, that was not the case.

“By the time I’d graduated, my parents had moved from Yorkshire to The Mumbles in the Gower Peninsula of South Wales. My father had taken a position as technical director of quite a progressive company called Replastruct, and I remember the boss had a Ferrari! So I lived there for a while and went through the unbelievably painful business of writing away for jobs.”

“My girlfriend at the time lived in North Wales and, after a while, I joined her. She had a flat which was the nearest building you can get to Conway castle. It was a fantastic place to live but I was on social security, there were very few interviews and it was just a nightmare. So I was looking for any work. I remember applying for the job of grave digger and another driving handicapped people on a minibus to and from a care home. I applied for a job in an aluminium foundry and by then I was lying very heavily about my qualifications. I said I had two O-levels and even that was too much for them. If only they’d known I had a first-class honours degree!”

“Interestingly enough, our external assessor, Bill Moggridge, offered me and one other student an interview with Moggridge Associates, but the other guy got the job. I think the right guy got it because he was much better suited to it than I was. So, people were getting jobs but, rather like my industrial placement, I was the last to get something.

“Then I got a telegram! It was a GPO product which they would wire through and it was from John Pemberton. I’d never had a telegram in my life before. A telegram was usually one line of words – very short, and this one said ‘Call me ASAP.’ I thought, ‘Who the hell is ASAP?’ There were no dots to indicate it was an acronym so it took me two days to figure out ASAP!

“So I rang John and he said, ‘I’m moving on. ITT are starting a new design unit based in Harlow,’ which I think was to become the company’s European design centre. They were quite large, a bit like Phillips, really. He was heading up the design team there and Clive was looking for a replacement.”

“I thought, ‘You must be joking. How can I replace John Pemberton?’ I was just a graduate; it was ridiculous. To cut a long story short, I went down for an interview. By that time they had their offices, which they were sharing with an architect called George Vickers, at 6 King’s Parade, Cambridge, so I walked there from the station.”

“The company had the first floor frontage, right through to the back, but the ground floor was a Lunn Poly travel agent and there was a classical record shop next door. John Pemberton had a room at the back overlooking, what was then, the car park of the Eagle pub. Clive shared a partitioned room with his secretary, Molly Pearson, overlooking the clock tower of King’s College. Brian Flint was on the top floor with Jim Westwood and Pete Maydew. And that was about it.”

“I showed Clive some of my work and, I don’t remember exactly, I think he just said, ‘Well, when would you like to start? We’d like you as soon as possible.’ So I started in December of 1979.

“I already knew a lot of people by then. I’d got very friendly with Molly and her friends when I did my work placement years before. It was a strong social network at Sinclair and people played hard as well as worked hard. So we all went off to the Ferry Boat pub that night and I think I stayed the night at John’s house. I remember Molly coming over to me and saying ‘Rick, you’re looking very glum.’ I said ‘I don’t mean to be, but I don’t see how I can do John’s job.”

There was going to be an overlap period but it didn’t seem very long, I think it was a couple of months.

“I remember talking to John about my worries and he said “Well, it’s just common sense. You just apply common sense to everything and the bits you don’t understand you just muddle through somehow until you do.’ So I thought, ‘Right, so it’s common sense!’ Interestingly, my primary school motto was ‘CS equals common sense’, and the headmaster drove this common sense mantra quite strongly!” TF

Part 2 of this interview can be found here: Part 2

Also see the interview with Sinclair electronics engineer, Brian Flint here: Part 1