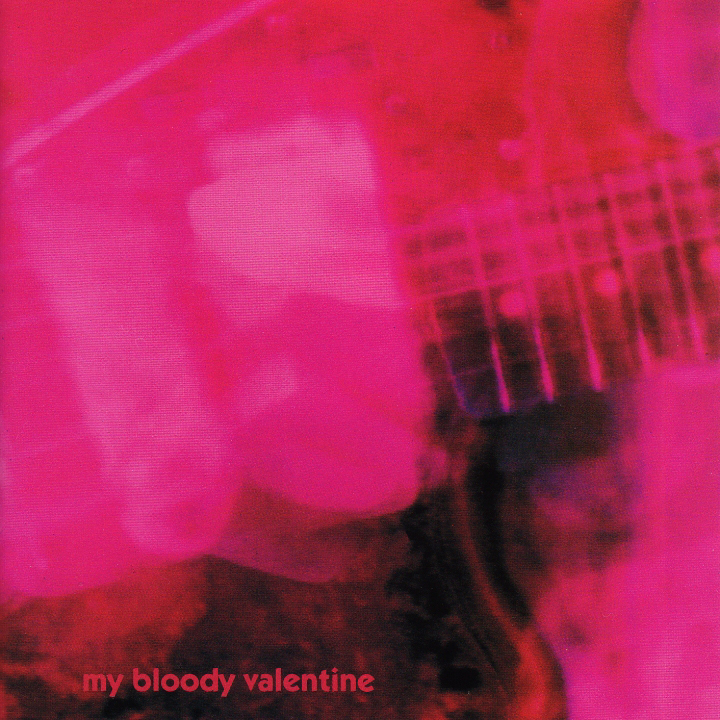

Twenty years after its release, My Bloody Valentine’s second album, Loveless, is regarded as something of a masterpiece, yet at the time the story of its production threatened to overshadow the music. Contrary to its title, the album was a labour of love for guitarist, writer and singer, Kevin Shields, who spent two years battling to get the ideas from his head onto tape. Alan Moulder, the engineer who helped Kevin realise his goal, explains how the album that almost bankrupted Creation Records was made.

Loveless

“By the time I came in, Kevin was fed up with fighting with people,” says Alan Moulder, reflecting on the problems Kevin Shields was having during the recording of Loveless; an album that eventually took him two exhausting years to complete. “Creation had just come out of a distribution deal and money was short so they were putting My Bloody Valentine in budget studios and Kevin was struggling because quite often the engineers were also the studio owners and if anything was going wrong they would try and cover it up. So Kevin would not trust them and would move to another studio.

“Some of those studios were on a shoestring budget so they didn’t have full-time maintenance staff and there were always things that didn’t get fixed. Kevin would say something like, ‘I don’t think that mic is working properly,’ and the engineer would argue, ‘Oh yes it is!’

“They’d look at him as if to say, ‘Well, what do you know? I’m an engineer; you’re just the guitarist in an indie band!’ But I learned very quickly that if Kevin thought something wasn’t working, 99 percent of the time he was right. He has incredible hearing.

“Kevin’s comment was always, ‘I just want it to be decent,’ so from his point of view, quite rightly, a faulty microphone isn’t decent. He didn’t want something out-of-this-world, he just wanted everything to do what it should do.”

Although Creation Records didn’t have the finances to book My Bloody Valentine into major London recording studios, they could see that the band’s fan base was growing rapidly, and that it was worthwhile supporting Shields in his quest to get things right. Their solution was to hire Alan Moulder, who already had a reputation for getting good results. Alan was reassured by Creation boss, Alan McGee, that the project would take no longer than three weeks to finish off, and so he accepted the job and began assisting on the mixing of the band’s Glider EP.

“I got involved because I knew Alan McGee,” Alan explains. “I’d recorded Automatic for The Jesus and Mary Chain and Alan thought that that record sounded slick. So I was brought in as somebody who was considered to be a properly trained, posh engineer, who had worked on chart stuff like Depeche Mode and the Eurythmics. To Creation that meant high quality and that’s what they wanted me to bring to Loveless.

“So we’d go to a studio and if Kevin found that something wasn’t working properly, he’d leave the room while I’d investigate and deal with it. In the end he trusted me so that if I said it was fine, he could move on without having any niggling doubts in the back of his mind. And most of the time he was right, so I would go through it with the studio until it was fixed, or we came up with a way around it.

“The first thing I did with Kevin was mix the four-track Glider EP, and when I say mix, I was doing what I was told! Kevin mixed it and I was the engineer. That’s how we got our trust and a working relationship that was good.”

Assault & Battery 2 Studio control room: Alan’s current studio in West London

Recording The Bass

By the time Alan started work on Loveless, some time around the start of 1990, the drums and some of the rhythm guitars were already recorded. Although there had been some problems tracking the drums, Alan remembers that Kevin was reasonably happy with what he had on tape.

“Even back then Kevin really knew what was good quality was and what he would and wouldn’t settle for,” insists Alan, “so everything was good quality. The rhythm guitars were down and sometimes there was a guide bass, but the rest of the parts were in Kevin’s head. So we went through doing bass on all the tracks. We used a Steinberger bass with no head, so it was very ugly looking and nobody ever used it live, but it had a consistent tone that worked well with layered guitars.

“Before that they’d been using a Warwick bass which sounded better if you compared the two in solo, but in the track the Steinberger used to cut through. The worst thing about a lot of basses is that certain notes ring out, maybe 20dBs louder than other ones, which drives you nuts. This one was very even up and down the neck.

“I thought it sounded very good and Kevin liked it, but it had to have these specific Steinberger strings and we were changing them three times a day. Kevin always had to have the strings very fresh on guitars and so he’d change them as soon as they had lost their zing. So we cleared the whole of London out of these strings.

“He also had a Vox Tone Bender distortion pedal and used that on the bass pretty much all the time. There are lots of different models but he had a great one.”

“The bass went into a vintage Ampeg SVT amp, which was a pretty standard bass amp in those days. It was a big valve one with an 8×10 cabinet. We rented most of our amps from a vintage guitar and amp supplier called Harris Hire, and I’m sure it was one from them. Ampegs vary a lot but we got a good one.”

To capture the sound, Alan remembers positioning a Neumann U87 about three inches from the Ampeg and also believes that there was DI recording taken at the same time. The policy for recording was to eradicate the sound of the room and to avoid using compression, hence the need for a very consistent bass!

“Kevin didn’t like any room sound so the mics were as close as possible,” Alan recalls, “and we may have put a blanket over the whole setup to make it even deader!

“Compression wasn’t allowed; Kevin didn’t like it. I managed to get away with a tiny bit of compression on the backing vocals because I asked if I could try it and he said I could as long as he couldn’t hear it. But he’d test it by shouting into the microphone and if he could hear it ducking down he’d say there was too much compression! But his singing was about 15dBs lower than the shouting so really there wasn’t any compression at all.

“And there is no point ever trying to get one over because if you are caught out then the trust has gone, so you can’t do that, but the compressor added a tone that I liked, so I didn’t care. It sounded good and that’s all that mattered. I didn’t really do much creatively as an engineer at all.”

As for the bass DI signal, Alan can no longer recall whether or not it was used: “I’m pretty sure we recorded a DI but I can’t remember how we balanced it. We didn’t mix it to tape so they were on separate tracks if we did do one.”

Taking The Lead

After the bass, Alan remembers recording the lead guitar parts, but says that there was no consistent methodology. “Each song had a different approach. Kevin would have an idea for different amp and pedal setups and we’d try them out. On one song, for example, there were two amps facing each other, quite close together, with different tremolos on each amp and mics in between, so there was some kind of pulsating sound, as if they were pushing and pulling against each other.”

Kevin’s distortion sound was mostly created using effects pedals rather than the guitar amplifier settings. The pedals Alan most clearly remembers were the Roger Meyer Octave Fuzz and Active Fuzz. “We were using them a lot,” Alan insists. “Kevin used the Active Fuzz and Octave Fuzz together because you could drive the Octave Fuzz so that would respond with a weird gating effect. It would decay to a point and then shut the notes down in a way that he liked.

“But he had lots of other pedals too and he’d pick certain ones for a track. We had a Digitech Whammy pedal that did octaves when you pushed the pedal down, which he liked. He also had a wah wah and some other fuzz pedals including a Jim Dunlop one, I think.

“I seem to remember, all the rhythm guitars went through a 1960s Marshall head with an old 4×12 cab that matched the amp, and also a Vox AC30. The signal was split between the two amps and they were close mic’ed with SM57s right on the cone. I always mic guitar amps right on the cone and usually in the middle. If there are four cones I just pick the best one. Sometimes the cones sound different if the cab has been used on the road a lot, but normally they sound pretty similar. Sometimes I put a Shure SM57 and a Sennheiser 421 right in the middle as close to the grille as I can get, because I find that if I balance them 50/50, that generally sounds exactly how it sounds in the room, but on the Valentines I had one SM57 on the Marshall and another on the Vox. The guitars Kevin used for recording were normally a Fender Jaguar or Jazzmaster.

“We’d usually experiment with the sounds for quite a while and then he’d change the strings. Once we’d got the sound right I’d set the tape machine to cycle and leave the room, and he’d practice for about an hour. I’d be sat outside and he’d just be there on his own working it all out. For Kevin, it is not just the way he plays it, but also the way he makes the effects work and the way his guitar responded to the distortion.

“Eventually he’d say he was ready and we’d change the strings again. We’d record it all from top to bottom three times onto three different tracks. Then he’d pick one and say ‘Yes, that’s it!’ and it was normally the third take. There were never any drop-ins or any track comping – it would always be a complete performance.”

Coming and Going

Throughout the production of Loveless, Alan received many offers to work on other projects, the most notable of which was the Hormonally Yours album by Shakespeare’s Sister, which he completed in a couple of months. On another occasion he found time to mix Transvision Vamp’s album Little Magnets Versus the Bubble of Babble, again completing it and then returning to carry on with Loveless.

“I was doing very varied stuff at the time,” he recalls. “I worked on Loveless in lots of sections because I’d be offered a project and I’d ask Kevin if we’d be finished in time. He’d say, ‘Yes, we’ll be done by then,’ so I’d accept the project and, of course, we wouldn’t be finished and I’d have to go away. But it was good because we were working very nocturnal hours and the pace got slower and slower, so having a break meant I came back re-energised.

“But I kept coming back because I liked working with him. It was long, weird hours, but being in a studio with Kevin is fun. Even if you are not working you are having an amazing conversation. The guy is very interesting to be around so I felt I was part of something special.”

Just before Alan departed to work with Shakespeare’s Sister, Kevin started experimenting with a sampler to create some guitar textures for the song ‘To Here Knows When’. This was done by recording lots of guitar feedback to DAT tape, and then turning it into Akai S1000 samples which could be triggered from a keyboard. To Alan’s surprise, the experiments were still ongoing when he returned several months later. Alan attributes the slow progress to the new sampling technology, which not only took some time to master, but also offered the band the chance to try out new musical ideas.

“We’d started off moving at a fairly brisk pace, doing bass on maybe two or three tracks a day,” Alan recalls, “and then we got into the guitar overdubs and were doing one song a day. But after that Kevin’s energy was sapped and it started to become a slog. When I returned they had already been working on the sampling for eight weeks and I worked on it for another two weeks after that, so it was pretty slow.

“The sampling was uncharted territory. We didn’t know the gear properly – we had just gone from the S900 to the S1000 which was a massive jump – and there were lots of possibilities to explore. I remember there was what sounded like a blur of notes to me, but Kevin could hear that some were cutting off and weren’t playing properly, and we couldn’t understand why. Now it is obvious: we had overused the polyphony, but at the time we couldn’t work out why it wasn’t playing back. I don’t remember solving it but we managed to get it so he liked it.”

Alan believes that Kevin’s guitar feedback sampling experiments were an attempt to achieve a sound which had the same qualities as those of the flute, having previously used a flute sample on the track ‘Soon’.

“Kevin was into the flute,” explains Alan. “There is something organic and pure about it that he liked and the sampled feedback seemed to have a similar tone. The thing about the feedback is that it changes the longer you hold the key down, so you get all these weird changes and a bit of discordance and randomness that he liked as well.

“In the end Kevin mixed the feedback quite low in the track but it was the right level. It gave the song this bubbling little tone underneath. It is quite subtle but you couldn’t take it out because it was a major part of the track. Of course, the great thing about those records is that there is actually not that much on them. Pretty much everything fits on the 24-track, so, compared with records today, it’s pretty simple. It was all about sound and performance.”

Tape and Voice

Although Loveless was recorded in a large number of studios, Alan was able to get a consistent result by lining up each tape machine at the start of the session. Most sessions were done on Otari MTR90 24-track machines which, according to Alan, the lower-end studios tended to use because they were considerably less expensive that Studers.

Before starting work on the lead vocals, Kevin took the unusual step of laying down the album’s backing vocals without any lead vocal guide at all.

“It was amazing,” says Alan. “I kept saying to him, ‘Do you not want to put a guide vocal on,’ and he would say, “No, I know what it is going to be.’

“We built a sound booth with a blanket over the top so that it was completely dead, and we had a Neumann U87 going into a UREI 1176 compressor, which was set on 8:1. I always tend to use higher ratios, but if the gain reduction needle moved I’d be amazed. It didn’t really do any compressing, but just running the signal through the 1176 adds a nice sheen to the top end. There was no EQ, or if there was it was very, very minimal.”

One aspect of the vocal recording Alan recognises as being different to how most people work today was the use of the in-house mixing desks preamps, rather than dedicated preamp hardware. “Nowadays everybody brings in vintage Neve 1073s and API mic pres; but we only ever used the desk,” reveals Alan. “We worked a lot at Protocol Studios which had a Soundcraft and a DDA, so we were not using high-end mic pres. I remember doing the backing vocals in room B at Protocol on a Soundcraft.”

“The tambourine, which Kevin played, was recorded using the same U87 setup, but without the tent. He’d stand about three feet away from the mic and play. He was very good at playing the tambourine – it’s not easy.”

The lead vocals were the last tracks to be recorded, by which time Alan was being called away to work with The Jesus and Mary Chain and Swervedriver.

“I was there for a couple of the lead vocals,” says Alan. “Quite often you work on tracks that sound amazing, but when the lead vocal goes on it is a disappointment because you have a certain expectation, but none of the Loveless ones were like that. They were at least as good as I’d hoped they would be, and some were better. That’s pretty good when you’ve been hearing the backing tracks on their own for about a year. I remember thinking that was quite remarkable.”

Although Alan didn’t mix the album, he did find time to visit The Church studio in Crouch End, to see how the mixing was coming along.

“Kevin was sub-compressing the drums pretty hard to get them to cut through,” remembers Alan. “It’s the age-old mix problem that we all have to fight with when there are really loud, overwhelming guitars. It is hard to get the whole drum pattern loud without it taking over, and if you are compressing it hard and you hit a cymbal, that’s all you hear, because the cymbals and hi-hats get through the compression.”

Another factor which made it even harder to balance the drums and guitars was Kevin’s dislike of panning, as Alan explains. “Getting your drums to cut through is not easy if you have everything in the middle and most of Loveless is mono. When I mixed with Kevin on the Glider EP, I said ‘Everything is down the middle, Kevin, do you not want to pan anything off?’ He said ‘No, I don’t like it.’

“I remember getting away with panning the tambourine slightly to the right because he couldn’t hear the difference, but that was the only thing. If he couldn’t hear it, he didn’t mind.”

Assault & Battery 2 Studio

Release and Reception

Today, Loveless is widely regarded as one of the most influential records of the 1990s, but when it was released, at the end of 1991, it received mixed reviews. Alan believes that the recording process overshadowed the music, and that the expectation was too great.

“As we were making the record, the Glider and Tremolo EPs came out and the band was getting bigger and bigger. Everyone was massively influenced by the previous record, so their reputations and their cool points were going up through the roof. You could feel that, but you also felt the pressure and expectation.

“When Loveless came out you couldn’t read a review that didn’t go on about how long it took to make. Everyone was saying, ‘Why did it take so long?’, but the important thing is the quality of the record.

“It’s good that Loveless is now so revered because Kevin put his soul on the line. I remember when it was being mixed he was talking to me about how he thought he was losing his mind, and his hearing! He’d toiled over that record and by the end it had just about sapped the whole of him.” TF

Want to know more about Alan and his studio? See our in-depth interview with him here: Assault & Battery 2 Studios: Alan Moulder