In Part 2, Robert explains how he does his vocal production, and describes the mixing stage of In The Cards

Vocal Production

Robert’s estimate is that approximately 75 percent of the vocal recording was his own, which he made in his LA home studio using a Wunder CM67 large diaphragm condenser fed into a Neve 1073 preamp. Other studios were used to complete the vocal recording, but Robert and his co-producers and engineers settled on a very similar gear setup in each one.

“The Wunder is basically a Neumann U67 knock off,” explains Robert. “They are made in Austin Texas. I did an A/B test with a 67 and I don’t think there is too much of an audible difference, but the price difference definitely made it worthwhile. That goes into a Neve 1073, which is pretty much my standard vocal chain for recording on the way in. I keep it pretty simple. I also have an (Empirical Labs) Distressor and every once in a while I used that on the album. That was when I was doing yelling vocals and wanted to hear the effect on the way in. But I tried to avoid it because I knew that during the mixing process we’d be using a lot of hardware stuff and I wanted to make sure that there were options. I didn’t want to destroy my vocals the first time around.

“Then, depending on what people had in their studios, a lot of times I’d run it through a (Teletronix) LA2A for compression. Once it’s in the computer I try to avoid using tonnes of vocal compression but you end up adding one layer of compression each time just for the peaks and by the end with all the layers you’ve smashed the vocal!”

Apart from Robert’s voice, which is highly processed for the most part (see the Vocal Robotics box), the only obviously acoustic sound that appears regularly across the tracks is that of a piano. It is particularly obvious on the minimal verses of ‘Long Way Down’, but even there the instrument is heavily processed.

“If I remember right, they were Logic grand piano samples on ‘Long Way Down’,” Robert recalls, “but they have been filtered so many times that they sound like something totally different. I think there are three or four tracks on the album that have real piano on them, but that wasn’t one of them!

“There’s a real piano on ‘Pass Out’, ‘That’s What We Call Love’, ‘Born to Break’ and there are a couple of other spots where I’m using weird samples of piano. But some things get so obscured with the effects and filtering that they end up just being more of a synth sound anyway.”

The Big Effect

Almost all of the tracks on the album are treated with massive reverbs and carefully positioned delays. Robert explains that these were delivered via four or five effects sends which he had setup on standby for almost every track.

“I’ll have a long tap going on, which is usually a quarter note or a dotted quarter note tap thing. Usually for that I use Waves H-Delay plug-in. I also use the Logic Tape Delay sometimes. There were couple of times on the album I got to use some hardware units but to be honest, a lot of the time I find a delay is a delay.

“Then for reverbs I use Lexicons and the Logic Space Designer reverb a lot, and I’ll always have a Giant Hall setting.

Interestingly, Robert used the same side-chaining technique that he had applied to the drums to duck the reverb each time his vocal was in action, but this time the aim was to achieve clarity rather than power.

“A lot of my reverbs I’ll side-chain against the vocal,” he explains, “so when I’m singing you can very clearly hear what the words are saying. Then immediately after the words are over the reverb, or the big delay, will fade in right behind on the leading edge. It’s just to make sure there is clarity, and then you hear the space. For the hyper-compressed music that I do I find it’s the only way to make it audible.”

Multiple Mixers

To ensure that Robert’s songs achieved their commercial potential, Glassnote assigned each track to a different mix engineer. Robert attended all the sessions and found it very interesting to see how everyone’s methods of dealing with his work differed.

“The songs are all in very different spaces so it was fun to be able to pick and choose different mixers for each one,” he says. “We chose each producer based on track appropriateness.

“I worked with Andrew Dawson on ‘Long Way Down’. That mix was a long process because we wanted to get it right knowing that was the lead single on the album. It took three or four days. Also it was something totally different for me so it was a challenge. Before that my stuff was mostly house based or more up-tempo. There is a lot of space in that one, so for me so it was new, and more slick and pop compared to a lot of stuff I’d done before.

“But Andrew has worked with Childish Gambino and he did a whole bunch of Kanye West albums, so he’s more of a hip hop man, and was a good match for that tune.

” I worked with Luca Pretolesi on the first and second-to-last track and he’s more of a dance music guy. I found that he was mixing his stuff in very different ways to Andrew Dawson.

“Then I worked with these two guys, Xandy and Wally of Wax LTD, on ‘Born To Break’. I showed up with a finished production thing and they just found a way to make it sound more clear or whatever, whereas Luca hypes everything to make it sound super dancey and with a thumping kick.

“‘Don’t Wait Up’ is more like a weird ’80s throwback, in a way, and we used Rich Costey for that. So it’s all very different.”

Like many modern pop productions, Robert’s album is very loud. Inevitably, it was pushed hard at the mastering stage, but the mix engineers also set about delivering loud and punchy mixdowns.

“On a lot of these tracks we really pushed the envelope to see how much harder we could slam that synth there, or whatever,” continues Robert, “so the whole record to me was how far can we push this! Each mixing engineer had their own secret method. For instance I worked with Tony Maserati on two of the more pop-like tracks and he has his own crazy analogue summing chain with his own propriety bus compression that I’m pretty sure no one else has! I honestly have no idea what he was doing but it sounded great.

“Rich Costey on ‘Don’t Wait Up’ had his standard drum chain that he ran everything through and it was a series of four compressors and a bunch of EQs and everything was multi-ed out then came back in some way.

“Everyone was using some sort of analogue summing, but before that for vocals it was pretty standard stuff, like an LA76 for nabbing some of those peaks, and people trying Distressors on some of the stuff. But the drums are all over the place. Some of that drum stuff, especially the sampled stuff, ended up staying in the box the whole time. It totally depended on the mixer.

“I think you can hear that each track has it’s own sound but, then again, some of that stuff is very subtle and in the end there are a million ways to get to the same result.”

When asked how he managed to maintain consistency when using so many different mix engineers and song writing styles, Robert admits that he’s not sure how it all came together.

“I wonder if there is any consistency,” he laughs. “Obviously there are a few factors that are always going to be there: my sense of programming and production and my vocals always tie things together sonically. Plus I sat in on all the mixes, so I was guiding them back to my way of thinking about the tracks.

“We had done so much production stuff that I found that mixing was a matter of filtering through all that stuff and finding what things were important. I like getting to the core. It’s vocal and drums, and the you’re figuring out the bass and the some sort of synth and making sure those things are super present. Then you’re letting all the cool stuff fill in the gaps.

“It was interesting taking all those final mixes to the mastering engineer and saying ‘Here you go, good luck! These things all sound pretty disparate.’ But there’s a common thread.”

For mastering, Glassnote hired Emily Lazar, Chief Mastering Engineer of The Lodge in New York. She was asked to cut the album loud, but also to find a way to match up all the different productions.

“She did a really great job of unifying all these things and making them all so fucking loud!” laughs Robert. “She’s great though. My label had worked with her a couple of times but I’d worked with Big Bass Brian Gardner before this record so I was a little reticent about trying somebody new, but it turned out really good. It was definitely right on the edge of maybe being too loud, but that’s kind of fun.”

Vocal Robotics

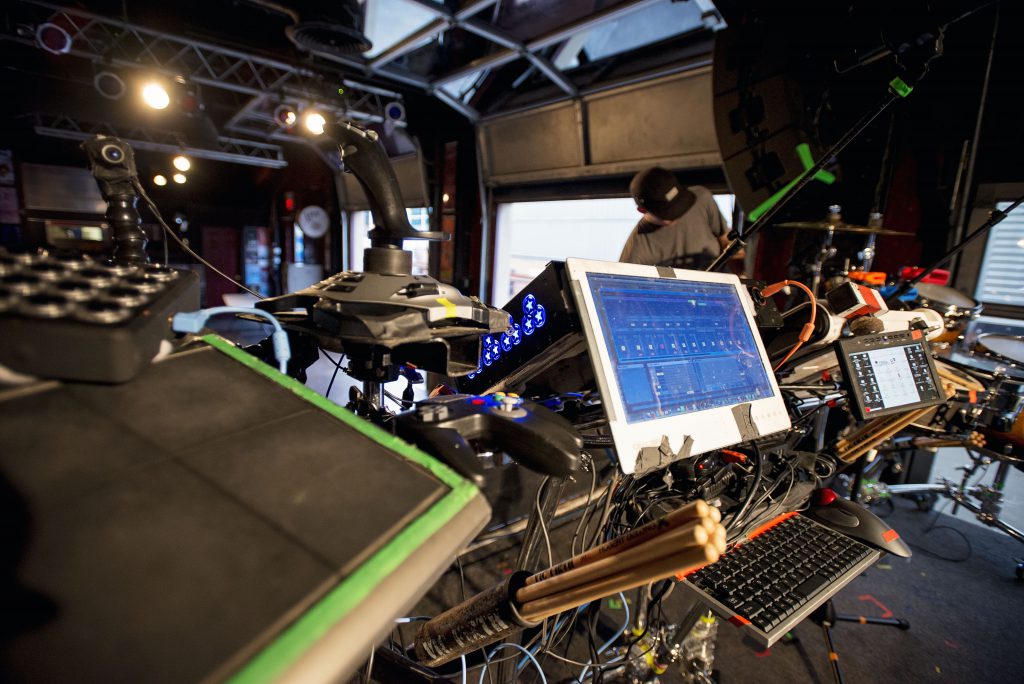

One of Robert’s signature production techniques is sporadically triggering dramatically pitched vocal stabs (instead of singing from one pitch to another), resulting in an appealing robotic effect. He uses the technique on ‘Long Way Down’, for example, to create part of the main hook in the chorus. In the song’s promotional videos, Robert appears to trigger the vocal samples using a DJ Tech Tools MIDI Fighter and uses a standard games joystick to swoop from pitch to pitch. However, the original work as heard on the album was achieved using quite different tools.

“All that vocal pitch shifting stuff is pretty much done in the box at the recording production phase,” admits Robert. “I draw all that stuff as automation then find ways to recreate it live later on. The MIDI fighter is something I use a lot. It’s fun because it’s got a giro inside so I can twist it around and up and down in my hand and it will send me the information and I’ll find a pitch shifter or whatever. I do the same thing with a gaming steering wheel on stage too.

“If there is something very specific that I can’t recreate by pitch-shifting live vocals I’ll assign it to a pad and trigger it. But sometimes I’ll do things like have a second ‘effects’ mic and feed that to the MIDI fighter or the steering wheel, or use Autotune to transpose my vocals.”

Part 1 of this interview can be found here