In Part 1, Terry talked about how he came to be an actor and won the part of Mike Tucker in The Archers, explaining how the show is produced and what is expected of the cast. In part 2 he talks about Doctor Who and Davros, his approach to acting and attitude to life.

Becoming Davros

A decade after landing the part of Mike Tucker, Terry was asked to play Davros in Doctor Who. The character had been introduced in a story called Genesis of The Daleks, which was broadcast in the spring of 1975. Michael Wisher was the actor who created the part, portraying the crazy scientist from behind a mask and seated in a mobile chair looking very much like the bottom half of a Darlek. Three years later the character was revived in a new story called Destiny of the Daleks. Tom Baker was still playing the Doctor, but this time David Gooderson was the actor in the mask. Davros was fast becoming one of the most popular Doctor Who villains. His relationship with the Doctor was akin to that of Professor Moriarty and Sherlock Holmes, or Ernst Stavro Blofeld and James Bond.

After Peter Davison took over as the Doctor, a new instalment of the Davros saga was written. It was called Resurrection of the Daleks and its director, soap opera specialist Matthew Robinson, contacted Terry to see if he’d be willing to replace David Gooderson.

“The reason I got into Doctor Who was because I did a TV series in 1982 called Radio Phoenix for TVS, which was directed by Matthew Robinson. He’d been asked to do Doctor Who so he rang me up out of the blue and asked me what I knew about the series. I used to watch it in the Hartnell and Troughton days so I knew about the Daleks, but I hadn’t a clue about Davros because I’d stopped watching when I went to University.

“Matthew asked me to take a look at the tapes of Genesis of the Daleks, saying that they were bringing Davros back but wanted to recapture the dark quality of the Michael Wisher episodes. They thought that the story line of Destiny of The Daleks with Dave Gooderson hadn’t worked very well because it came across as a bit of a send up.

“I thought it would be an interesting technical and artistic exercise to work within a mask, because the character came very much through the voice.”

Dave Gooderson had been unfortunate enough to have been given Michael Wisher’s old mask, which didn’t fit him particularly well and must surely have come unstuck during Davros’ rants. For Terry, the production team had a new mask made, however it then sparked endless arguments amongst fans about which was the right Davros!

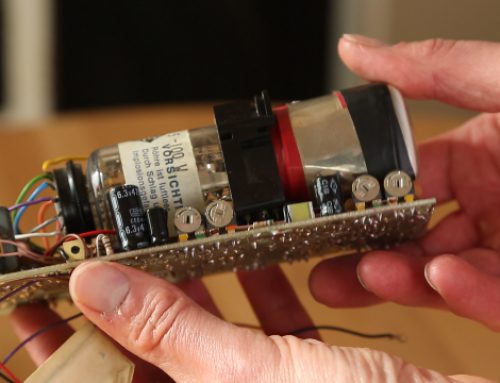

To create Terry’s mask, the special effects team started by taking a mould of his head. This they did by rubbing petroleum jelly over his eyebrows and eyelashes, then covering his face and head with alginate and plaster of Paris.

“I had to wait a good hour while it all set,” Terry recalls. “It was horrid because it compressing my skull into my neck and I had to have straws up my nose to breathe until they finally crack it open and make the positive mould. Then they built on it from there. But it resulted in a mask that fitted me and we tried very hard to make as much of it move as possible.”

Acting From Within

Doctor Who viewers will recall that Davros’ eyes no longer work, so he has a large prosthetic eye inserted into his forehead. Obviously the eyes of the actor inside line up with the two that are closed making it rather hard to see out, although Terry’s mask did at least have little slits between the eyelids so that he could see something.

“I had no peripheral vision and was only able to see straight ahead because my head was bolted into the chair and couldn’t move. The controls on the chair were on long stalks so that I could find them with my fingers. Even that was hard because the hand that they had given me had elongated fingers.

“It was claustrophobic and it was hot but because the mask fitted so well I didn’t really notice how hot it was until I took it off. Obviously it also removed my ability to hear properly so I was very much in a world of my own.”

The Davros chair presented Terry with a few challenges of its own. Far from being an electric vehicle he could drive around, it was actually a bespoke prop which Terry had to manoeuvre by pulling on the studio floor with his toes.

“It was built on a base which was a little like a supermarket trolley in that it always veered in one direction when I was trying to get it to go the opposite way. And I was in something that was made out of four-by-two inch timber and had to share that space with the two 12-Volt car batteries that were powering the lights on the chair.”

To make matters worse, Terry was also required to deliver many of his lines as he struggled to move about. The Daleks added to the difficulties because they too had actors inside who could see very little of what was going on around them. To avoid filming delays, the performers rehearsed their moves at the rehearsal studios in North Acton prior to going into studio. Certain lines or words of dialogue were identified as cues for Davros and the Daleks, to start and stop moving.

“The plotting of movement had to be done very carefully so we didn’t crash into each other,” adds Terry. “It was all very carefully choreographed, but we tried to restrict the amount of movement as much as possible.

“The voice was done by me but was then changed slightly processed by the audio engineer, but not to the same extent as the Dalek ones were. There was a mic in front of my mouth, supported on a piece of wire, and that was fed to the sound control room. But on the studio floor they could only hear my un-processed voice.

“Obviously when I was speaking I knew that it was going to be slightly altered but I also knew that they weren’t changing it radically, so a lot of it had to come from me. But some of the way Davros speaks is informed by the restrictions of the mask. Having watched Michael Wisher’s episodes, I realized how he got to that voice. There was a certain authority and paranoia that went into the delivery, but you also had to move your mouth in a very particular way in order to make the mask move. In those days we didn’t have the super prosthetics that they have nowadays where everything is totally mobile. Then we were working within latex foam rubber masks which were thick, heavy and had little or no movement to them at all.

“I found that I had to adopt a very pedantic way of speaking which affected the phrasing of my sentences. Then I started to bring my voice down in tone and pitch and put a bit of harshness and paranoia into it, and before you know where you are, Davros had appeared and the Doctor must be exterminated! They just put whatever effect they needed to on top of that.”

“The Daleks were impersonally scary, but Davros is a person and yet he has this quality of a Dalek about him, which was very disturbing. My brief was to recreate what Michael had done as much as possible, so it’s my version of that same character. There was still the element of the intergalactic Hitler about it but we tried to get away from that a bit as we moved further into the series and instil some dark humour into the character.”

Who’s Who

When asked if he ever worked with any of the actors who played Doctor Who before Peter Davison, Terry appears genuinely sad that he did not get the chance. Tom Baker may still be treading the boards, but sadly William Hartnell, Patrick Troughton and Jon Pertwee have long since passed on.

Terry is, however, in the exclusive position of having played Davros opposite three different Doctor Who actors on screen, namely Peter Davison, Colin Baker and Sylvester McCoy, and with Paul McGann in a Big Finish Productions audio play released on CD. Of the television productions, it is Revelation of the Daleks he seems most fond.

“They were all very different but Revelation was a lovely story and Colin and I are great friends. We’ve always worked well together in all the stuff we’ve done. It was a very strong story for Davros and possibly more of a Davros story than one about Doctor Who. It also had a stunning cast, including Eleanor Bron, Clive Swift and William Gaunt.

“But I’ve also played Davros about 10 times since for Big Finish Productions. There was one with Paul McGann called Terra Firma which was really interesting because that focused on the game between the Doctor and Davros; both trying to knock each other off their pedestal. The Doctor was trying to push Davros into schizophrenia; into believing that he is actually the Emperor Dalek, and Davros was pushing the Doctor to face the reality that he is so alone. Davros had taken over the Earth and was showing the Doctor there was nothing he could do about it so may as well give up. That game was intense and really lovely to perform.

“The thing that we found when we started doing the Big Finish CDs was that Davros can exist without the Daleks, and what’s interesting is the game that he and the Doctor play with each other. It’s like a mental chess game. They actually need each other in an odd sort of way. They are both alone and the only one of their kind. And they are both intellectually so superior that they have found in each other the only intellectual challenge that they have ever really faced. And, in a sense, they both relish that game.

“I also did a four-part mini-series for Big Finish called I Davros which studied the Davros back story; seeing how he grew from a 15 year old boy to this monster who creates the first Dalek. We were looking into how this character came into being. I Davros finishes when the first Dalek speaks.”

It’s clear that Terry is rather fond of Davros and, like any good actor, has a certain empathy with the character.

“Some people say I am probably a little too close to Davros and Mike Tucker for comfort, but you have got to bring something of yourself to them. I’m not an intergalactic Hitler by any means but you have to empathise with the character, or at least some of the aspects of the character, in order to make it credible. Otherwise you are just producing a cartoon which is of no value.

“Fans ask me what’s it like playing an evil character and I say to them that I just play characters. Nobody is born a monster. Most evil is good intentions gone slightly awry. One person’s patriot is another’s terrorist.

“In Revelation of the Daleks, for example, Davros solves the problem of famine throughout the universe, but he uses other people’s dead bodies in order to do it. People are horrified, but he doesn’t see the problem because they are dead. They don’t feel anything and are not of any use to anybody so he uses their bodies to feed people.”

Revelation of the Daleks is indeed curiously ambiguous. Eleanor Bron’s character, Kara, initially seems like a fairly innocent and reluctant pawn in Davros’ horrifying scheme. However, by the end, her desire for power is revealed and it is Davros who comes out as the more likable of the two.

“Politicians can be just as bad,” agrees Terry. “Davros is not as slimy as her character. At least he is focussed on what he’s doing and makes no bones about it. The interesting thing we did in I Davros, was show his political ineptitude. He couldn’t see the point of politics at all. He was a scientist but was forced to become a scientific politician. He had an absolutely brilliant mind but zero ability to interact on a social level with other people.”

The New Doctors

After Terry’s portrayal of Davros in Remembrance of the Daleks in 1988, the character did not appear upon screen until a 2008 episode of Doctor Who titled The Stolen Earth. This time, however, the actor Julian Bleach was cast in the part. It seems a strange decision to choose someone else, given that aging 20 years can only be of benefit when playing someone as decomposed as Davros. Terry explains what he feels about the series since its revival in 2005.

“They have tried to develop and pull together scripts that are redolent of what had happened in, what the BBC now call, the ‘classic series’, where the sets might have been wobbly and shaky but they had good scripts and storylines and it was quite a dark programme. And in the main they’ve succeeded in doing that. They have used CGI but not to the point where it has become the all important factor, as it is with certain American sci-fi programs that have no plot.

“There have been very good episodes in the newer series, but there were some which, for me, were very pat and twee, and trying to be clever rather than actually doing the job.

“For me, the ones that worked best were the dark ones. Stories like Blink, Silence in the Library, The Girl in the Fireplace and The Empty Child. I don’t pay a lot of attention to credits, but the ones I tend to rank as my favourites were the ones written by Stephen Moffitt who is the current producer. There is an unfinished dark quality to his stories which I think is part of the essence of Doctor Who.”

The Shadows and the Limelight

Most people with a television in the UK have probably seen Terry’s face on their screen at some time or other. His credits include such well-know programs as Crossroads, The Bill, Dangerfield, Kingdom, Casualty, Doctors, Bergerac, Angels and French & Saunders. Nevertheless, outside the theatre, the roles that have brought him a level of fame have been those of Mike Tucker and Davros. For Terry, such public anonymity is most agreeable.

“I have done a lot of television without a mask but I’ve always been in the shadows, which is fine as long as I’m getting work. I can do normal things like go to the Supermarket and nobody knows who the heck I am. I quite enjoy that. All I want to do is different interesting things.

“At the beginning of my career I thought I was just going to be a theatre actor, do my bit and hopefully end up at the RSC, West End or whatever, but working in audio changed that path and it has become my favourite medium because I believe it gives the actor the greatest range. On radio I can do things which physically I would never be able to do in TV, film or stage because you can use your voice to create the physicality of the body. You are painting the picture of that character with your voice and it is an interaction between you and the one other person who is listening at the other end of the microphone. It’s not millions, it is one other person.

“I imagine the situation I am in; the place and the characters I am working with. Then there is a mental throwing of the voice, as if you are allowing somebody else to overhear what’s going on.

“And there are dramas where you are dealing directly with the listener, but not acknowledging them as a listener. It is your thought process which you are transposing into the head of somebody else. For example, Risky City, the piece that won me the Pye Radio award for best actor, was an interior monologue. It all took place inside the damaged brain of this lad who’d had his head kicked in on top of a car park in Coventry.

“If you are doing a physical scene you will physically get involved in that scene because you are supposed to be digging a ditch or whatever it may be. If you are supposed to be running in a scene you have to physically act out the breaths and not just stand there saying words and then breathe heavily at the end of lines. You have to get involved in how that character is at that particular point in time and imagine what they are going through physically. If they are cold they must sound cold, whereas if they are hot they will have a different way of speaking.

“A sound effects person will tell you that cold water being poured into a cup sounds different to boiling water. People think you just pour cold water into a cup for a cup of tea but it has to be boiling because it has a different ambience and quality. Boiling actually affects the physicality of the water.”

Epilogue or Encore?

Now that Terry is fast approaching the UK’s official retirement age, he is in a good position to look back at his career to date and sum up what he has learnt about acting and life in general. After all, the maxim goes that with age comes wisdom!

“When I started off I thought I could do everything,” Terry admits. “The older I get the more I believe I can’t do anything. I’m amazed when people ring up and say ‘We’d like you to do this job.’ I usually think ‘Gosh, haven’t, they sussed me out yet?’ I don’t recognise the value of my acting skill because it comes naturally to me, but we all have our own talents.

“I’d always had a natural ability for doing dialects and accents but never thought of it as a skill – it’s dead easy for me. I just assumed everybody had that skill but I don’t think they do because people often ask ‘How do you do that?’

“I’ve always believed that it has got something to do with an affinity with music. Dialects have got very specific music and cadences to them. I’m talking about the rhythm of the language – the rise and fall of the vowel sounds. And if you have a good ear for music then you’ll be able to do dialects.

“There are also similarities with the breathing. Actors use their diaphragm to control the force and the power of their voice. That way you are not working in your throat all the time and getting tired. You are actually taking breath from your chest and I was used to breath control from my days of playing clarinet and saxophone.

“I suppose what I’ve learnt over the years is to be me and not live through other people’s lives. If I am too busy focusing on something that’s a fantasy then I’m missing out on the everyday things and those moments aren’t going to come again. It’s just a matter of relaxing and being happy in your own skin, I suppose.”

Relaxed or not, Terry has no plans to stop treading the boards just yet. After all, his works is his pleasure, so why would he want to? And then there is the small matter of money to consider.

“The interesting thing about acting is that it is not a linear occupation,” he explains. “People join the civil service and work their way up to become head of department and get a nice pension at the end. There is a progression of career. If you are an actor you are up and you are down and round and round in circles. You can be playing the lead one night and playing somebody with a couple of lines in the background of a scene some two weeks later.

“And actors don’t have pensions; what comes in goes out. For me, if the job is interesting I’ll do it, even if it is just a couple of lines, because I enjoy the process of working. There are people who earn a lot of money but the majority of actors will earn little over their lifetime.

“I can’t conceive of doing any other job because I have a low boredom threshold. It would drive me potty working in the same room with the same people for 30 or 40 years. I couldn’t do it. I’m coming up to 65 but I’ll just carry on working. I intend to be going until they cart me off in a wooden box. And hopefully I’ll die on stage or close to a studio door having just done a job.” TF

Actor’s Joke, as told by Terry:

“A guy who turns up at the gates of heaven and St Peter says to him:

‘Right, there are a few things we need to check before you go in. First of all, how much did you earn in your last year on earth?’

‘£187,000’ says the man.

‘Right, how much did you give to charity?’

‘About £20,000, I think.’

St Peter says ‘Fine.’

‘What did you do as a job?’

‘Oh, I was a barrister.’

‘OK, thank you very much, in you go.’

Next person comes up.

‘Can I just ask how much you earned in the last year of your life?’

‘It was about £97,000.’

‘OK, and did you give much to charity?’

‘About ten or eleven grand, I think.’

‘Good, 10 percent, that’s good.’

‘And what was your job?’

‘I was a politician.’

‘OK, fine, thank you very much.’

Then the next person comes along.

‘Can I ask how much you earned in the last year of your life?’

‘It was £4227.82.’

And St Peter says:

‘Hang on; didn’t I see you in The Bill?’”

Part 1 of this interview can be found here: Part 1