Having your life story published as a book and on sale in high street retail outlets should be thrilling and satisfying. Polymath Perspective’s guest, Lindsey Rosa, won a competition to have her story turned into a book but her experience was anything but good. She explains how she had to fight to make sure her truth was not made into fiction.

Lindsey Rosa

Firstly let’s be clear on one thing; the events I am going to describe to you are true. Every single detail has been painstakingly poured over and scrutinised to ensure that it is, as far as my memory allows, relayed to you with the utmost accuracy. You see, dear reader, I’m a stickler for truth.

It all began in September 2009. I was 29 years old, a mum of two, and struggling to find purpose and direction. Not an easy task given that every decision I made was informed by the mental illness I suffer from – anorexia nervosa.

Exclusion Zone

I was born into a strict separatist religious cult called the Exclusive Brethren, but at the age of seven I was kicked out, or excommunicated, as the Brethren like to call it, together with my parents and one of my sisters. From that point on we lived in social isolation from both the cult, which shunned sinners like us, and the world, which we believed was evil and run by the Devil! As you can imagine, my life was not like that of most other people.

Still, as children do, I got on as best I could and didn’t seem to be doing too badly without any social interaction. I thought about the future very little as my parents expected God to step in at any moment and sort out the predicament we were in. However, as I moved through my teens I became more preoccupied with what the years ahead had in store for me.Further education was considered a sin, or at least a threat, so I had no prospect of a career. Normally I would be expected to marry a nice Brethren boy by the time I was 19 or 20, as both my mum and sister had, but this was looking less likely as the years went by and the Brethren showed no signs of welcoming us back into their fold. So it wasat the age of 15, I started heading down a more sinister path into the world of anorexia. By the time I was 18 I was well and truly fed up with life. Anorexia had its teeth in me and refused to release its vice-like grip.

Fast forward 11 years: past six months in a clinic designed specifically to treat people with eating disorders; past numeroustherapy sessions during which I made countless realisations about myself; past the point I met Tom (my boyfriend and father of my children) and experienced what it was like to not be in control of my body, as it gave in to fear, adrenalin and anticipation; past endless conversations with Tom about the ‘point of life’ and ‘who I am’ (remember, all I had known were the restrictive beliefs of my parents who insisted we lived as Brethren despite our excommunication from the cult); to 2009, where I was still clueless about ‘who I was’ but responsible for two children who needed a stable mum.

You might think it was comforting to be reassured by friendson a regular basis that I had ‘come a long way’, but my healthy looking body disguised the painful truth: I didn’t feel a great deal different inside. My mind was still wired to think the negative thoughts that fuelled my anorexia, but I had become very adept at suppressing urges not to eat (or purge) and buried the inevitable anger and self-hate reasonably efficiently. Well, Tom knew different. He lived with me. Which is why, in September of that very year, he encouraged me to enter a national true-story writing competition with the chance to talk about my experiences on a television programme and have them published in a book. He said words to the effect of, “It might help you work though things in your mind and put the past to bed.” Well, I hated the idea.

Pen to Paper

Of course, within hours of stating that I most definitely was not, under any circumstance, going to enter the competition, I was scribbling furiously, and just as furiously tearing up what I had written in frustration at my lack of ability to say what I wanted to. At last I produced something I was reasonably pleased with and let Tom read it. I don’t remember exactly what he said about this first draft but I’m pretty sure it wasn’t desperately complimentary. I’m also sure he gave me some good guidance and encouragement and, at last, I produced a condensed tale of about 1500 words describing much of what I have told you.

I was reasonably confident thatmy story would be received with some interest. OK, so there are many people that leave cults and some that writebooks, but I felt that my experience of living between two worlds and my ensuing mental illness was a relatively unique set of circumstances. I felt excited about having the opportunity to finally expose the trauma, not merely of being in a cult but, more significantly for me, integrating into society having left the cult, for in reality that is the truly difficult part. Now that was something I had a hell of a lot to say about.

It turned out I was right about the interest. In early 2010 I received a phone call from a member of the production company team who were running the competition. She explained that I was one of many people who were being contacted to gather further details about their story. I was required to provide them with the contact details of a couple of people who would confirm that I was telling the truth and that my story was not a complete figment of an overactive imagination. One of the contacts I gave them was my lovely uncle who had originally been a member of the less fanatical Open Brethren but had left them many years before I met him. The other was my long-time therapist who was the first ‘worldly’ person I told about my isolated childhood.

Through an exchange of emails I explained my request to my therapist and she explained her reluctance to betray confidentiality. I reassured her that she wasn’t required to give any details of my experiences; just to confirm that what I had written was true. But therein lay the problem. She replied, and, I quote, “It is also not for the therapist to be the arbiter of whether a person’s story is true or not…” For whatever reason she was being pedantic and obstructive, but little did I know how ironic her questioning of truth would turn out to be.

In February I was informed that my entry had been shortlisted and I was invited to London to meet the panel of judges. My excitement and anticipation were only slightly marred by the ominous warning which came with the invitation:

‘…you have done incredibly well to get this far, but we have to remind you, you must keep your involvement in the show strictly confidential, as any undue publicity from hereon could jeopardise your place in the competition…’

‘Crikey,’ I thought, ‘I’d better keep my big mouth shut then.’

Face to Face

I presented myself to the judges clutching letters from my mum that she’d sent while I wasat the eating disorders clinic. The letters said that the Devil had got me in my weakened state. I felt that I was in some way betraying my parents by disclosing personal details of our life, but I ploughed on, reminding myself that this was my story; a recollection of my experiences and responses to an extraordinary situation. My intention was very clearly to talk about my life and not to lay blame or criticism in the laps of my parents who, despite strictly following the laws of the cult, loved me.

A few weeks after my trip to London I heard that my story was one of 15 chosen to be made into a short film. ‘Oh my goodness!’ I thought, but I couldn’t allow myself to get too excited because only five of the 15 winners would receive the book publishing prize. I felt that I was close, and suddenly really wanted that prize. To get so near and not win would have been awful.

Filming for the television series took place in March. I went to great pains to explain to the director that my story was ongoing. In other words, I would be really disappointed if, as so often happens, the film portrayed my journey as somehow concluding in a happy ending at present day. I really wanted to use the programme to draw attention to the ongoing difficulties I was experiencing in trying to integrate into society following my separation and how that manifested itself as a mentally crippling eating disorder. I wanted to dispel the idea that physical freedom bringsfreedom of the mind, for I am certain it does not. However, I realised that it would be near impossible to explain everything in the eight minutes allocated for my film. My consolation, however, was that if I won the book deal I would be able to talk freely and in greater depth.

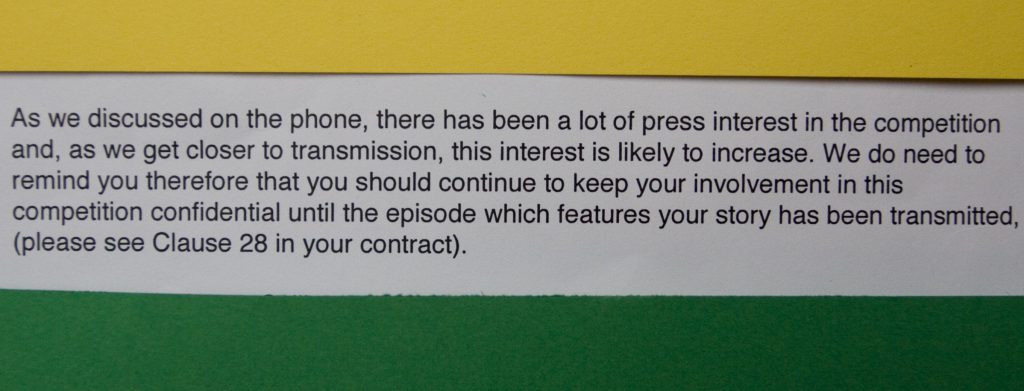

Filming over, I waited to hear whether I had won the book deal, which was due to be announced in May. Incredibly, I had been sent the publisher’s contract for the book in February and told that to progress further in the competition I had to agree to the terms and conditions. In other words, signing the agreement was part of the conditions of entry into the competition. I had no idea what the publisher intended for the book: the style or format that would be used. This contract also revealed to me that there was prize money or, as the publisher put it, an advance. Well, I can’t deny that this news made the prospect of winning even more attractive.

One of the five!

Clause 28

Brought to Book

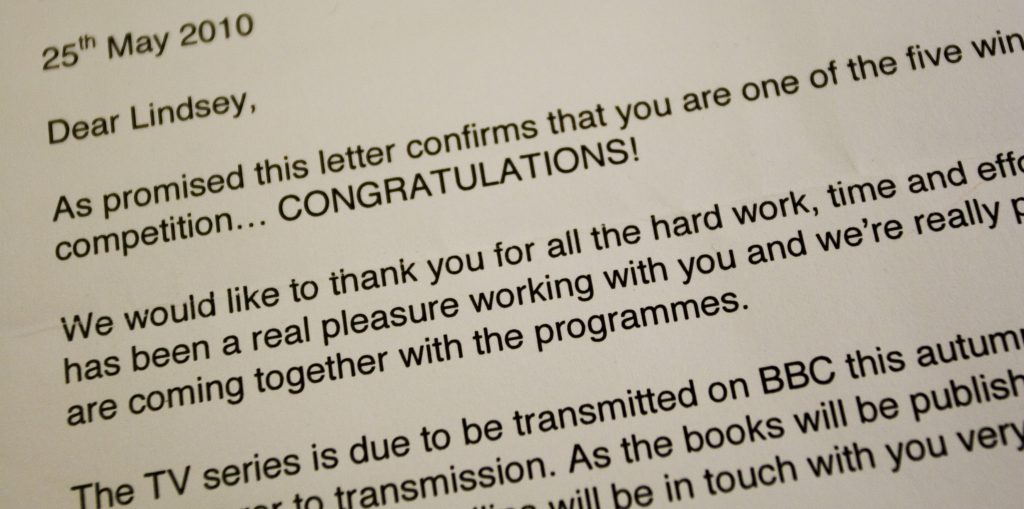

Eventually, on 17th May, I received the phone call I had been waiting for – and the news was good, great in fact: I had won a book deal! I couldn’t quite believe it until I got confirmation in writing a week later. Of course, the desire to share the news was overwhelming but I wastold verbally and reminded in the letter that, due to press interest, I should keep my involvement in the competition confidential.

I found the contract’s insistence that I didn’t inform the people I loved and trusted, such as my brother and Tom’s parents, very difficult to deal with. I’d already told my brother I had entered a competition and he was understandably interested to know the outcome of my submission. I remember trying to fob him off and feeling awful as I sensed his hurt at my insistence that I couldn’t tell him whether I had won or not! Fortunately he correctly interpreted my reluctance to talk about it and withheld any more questions to save my embarrassment. I felt I was being disloyal and this made me uncomfortable, but my submissive, unquestioning obedience to those in authority was typical behaviour for me at that time and, as you will see, set the course for the events that unfolded.

Given that the programme’s broadcast was scheduled for September, and that the books were supposed to be on sale the day after airing, I was aware that there was an incredibly tight deadline for the writing, editing, production and publication of the book. It was, therefore, a great relief when a woman rang me a few days later and introduced herself as my editor. I glowed from the praise she showered on me for my ‘incredible’ story, which I interpreted to mean she thought I was a brilliant writer. It was, however, sharply brought to my attention that I had misunderstood her meaning when she informed me that a ghost writer would be writing the book and that my job from there on would be easy. Having gathered myself, and feeling rather stupid for my naive supposition that I, a non-writer, would be entrusted with writing my book, I enquired who the ghost writer would be.

“We’ve got the perfect person,” she insisted.

Well, this sounded very promising. I wondered if it would be a woman with direct experience of eating disorders, or at the very least someone with an interest in mental illness. Maybe someone living close by so that we could get the writing process underway as soon as possible and hit the incredibly tight deadline. Or even someone like me, brought up in the outer suburbs of London and with an understanding of the common vernacular, humour and way of life in such a place.

“He’s an American, an expert in cults and he lives in Paris,” said the editor enthusiastically.

During the days that followed I looked him up on the web in an effort to learn more about his background and why he was the man for the job. After all, he was a stranger to me, and I was supposed to tell him every intimate detail about my life.

Tom restrained himself from fully expressing his strong doubts that a middle aged man had the ability to write the story of a young woman who suffered from eating disorders. He was also deeply concerned that I had been assigned a writer who lived so far away when the deadline for the book was the 2nd July, less than a month away. I’m ashamed to say I had none of these doubts, blindly trusting those I considered to be the authority, rather than Tom, who also wrote for a living, loved me and had my best interests at heart. Consequently, I had complete faith that the publishers knew what they were doing. I was on a high from all the special treatment and Tom knew better than to challenge me. Experience told him this would push me away and that I was going to need him over the next few months.

My first contact with the publisher, rather than the editor, was a phone call. I remember it was a Sunday and we were visiting Tom’s parents with the children. She told me that the publishing team couldn’t wait to meet me and that she’d love it if I travelled to their London office bringing Tom and the children with me. I was surprised and not a little disappointed therefore, when the ghost writer called me a few days later saying there wasn’t time for me to go to London and he wanted to crack on with the process of interviewing me as soon as possible. I agreed it would be most convenient if he came to stay at a hotel near me.

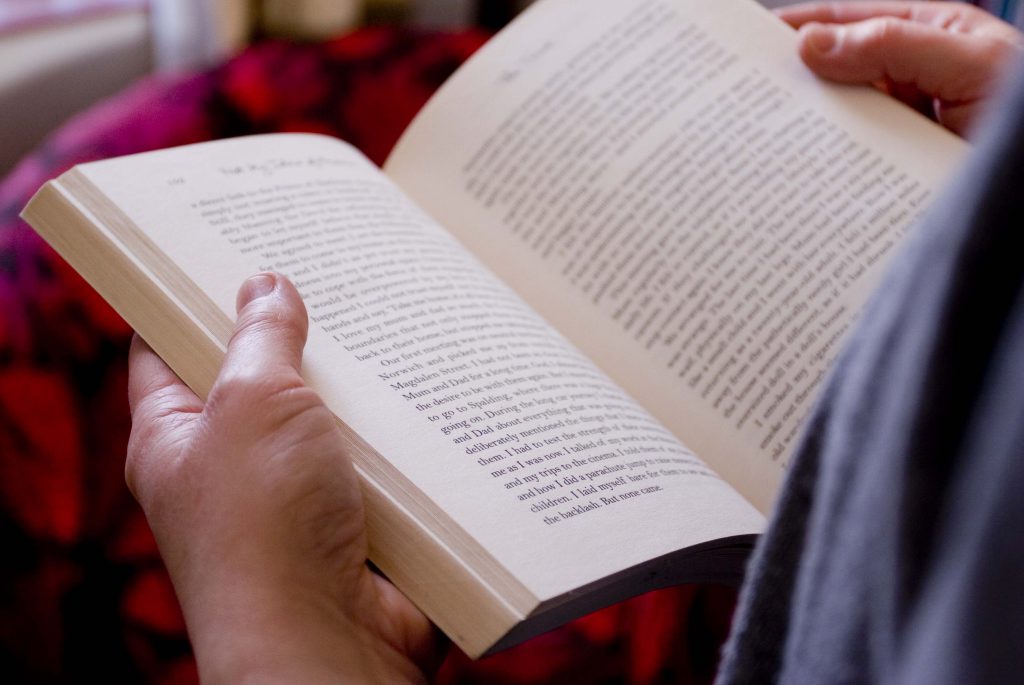

The end product…

Ghostly Apparition

I picked him up from the railway station and brought him back to the house to meet Tom and the children. This was Tom’s idea. He thought it important that the ghost writer had a feel of who I was in the context of my life and home. The ghost writer obviously didn’t. He wriggled uncomfortably on our sofa, casting his restless eye over our CD collection before focussing entirely on his mobile phone, which he fiddled with for 10 minutes in an attempt to locate some information about a progressive rock album that he felt necessary to share with us.

After the album was identified, Tom took the ghost writer into the garden, thinking that it would help him in writing the later part of the book in which he would need to realistically describe where I lived and where the children were born. Seeing that he had little interest in what he was being shown, Tom asked him if he wanted to look at my box of photographs to familiarise himself with my family members, and perhaps, more pertinently, the appearance of Brethren men and women.

I felt some sympathy with the man. After all, he had just spent a couple of hours on the train and probably just wanted to get to the hotel where he was booked in and the interviews were supposed to take place. I motioned as such to Tom who, determined to resolve the many doubts he had about the situation, enquired, “So how many books have you ghost written?”

“None,” he replied, “but my wife has written one.”

It turned out he had previously edited one book but was making a living editing a French lifestyle magazine. “So, how much do you think you’ll get done in the four days?” Tom enquired as we left for the hotel, apparently expecting the ghost writer to explain that it was the first of several sessions.

“All of it!” he said, rather surprised.

The next morning I returned to the hotel for a second day of interviews. The ghost writer triumphantly waved a book in my face. As he unashamedly read me extracts from his ‘how to ghost write’ book I worked to suppress my own feelings of doubt about the capabilities of the man sat in front of me. Four days of interviews flew and I was pleased to be left with the impression that he really understood me and, despite his seemingly strange behaviour, continued to believe he could pull everything together in time for the looming deadline. LR/PP

Part 2 of How True are ‘True Stories’? can be found here: Part 2