The first album collaboration between ambient composer Brian Eno and Underworld front-man Karl Hyde, is a joyfully experiment to find out what you get when you mix the musical styles of Fela Kuti and Steve Reich.

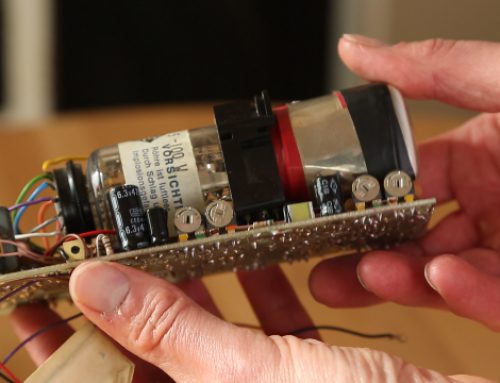

“It’s completely crucial for me,” insists Brian Eno, when asked if the technology he is currently using affects the way he makes music. “I couldn’t be a musician otherwise because I can’t really play anything! Everything I do is worked around electronic technology.

“All musicians use technology unless they are just singers; a violin is technology, for example, but the kind of stuff we are using here enables us to have so many possibilities. Mostly when we are doing this I am providing the rhythm track, which I am doing with loops or loops I make, like the last one that you heard, I made that on the fly by slowing down the other one and re-looping it!”

The enabling technology Brian is talking about played a massive role in the production of his new album, Someday World, which he wrote together with Underworld vocalist and founding member, Karl Hyde. Making the nine track album, which was inspired by the work of Steve Reich and the godfather of afrobeat, Fela Kuti, involved a great deal of improvisation and experimentation and the process has forced Brian reconsider his extremely hostile feelings about performing live.

“I’d sooner have somebody drive nails through my scrotum, generally, that play a live show,” Brian jokes, “but what we are doing here is exciting! It is much more dangerous because it can go badly wrong or just become very boring. If some of this feeling can go into a live show, where there is a real sense of discovery, where it is not just a routine that you do every night…”

“We took that risk with Pure Scenius,” adds Karl Hyde referring to a trilogy of live concerts that he, Brian, keyboardist Jon Hopkins, guitarist and sound designer Leo Abrahams, and the three-piece improvisation specialists The Necks, performed to audiences of up to 2500 people in 2009. The shows, which took place in Sydney, Australia, were so successful that Eno and company repeated the format in England at the 2010 Brighton Festival.

“There were moments during the shows,” continues Karl, “where I thought ‘We are going somewhere really bad any minute now and I don’t think we are coming back from the edge of this one,’ and that’s when you need Brian to go, ‘Right, we are going to change now!’

“But that’s important. We were all having to be attentive to each other. There was lots of looking and hand signals and reading each other’s temperaments and the mood of the audience. That was a thrill. Sometimes it wasn’t very good and sometimes it was amazing.

“You get higher highs, and lower lows,” confirms Brian. “The performances can be absolutely amazingly unexpected, or really shit. So it is about what level of risk you are prepared to take, really. I’d rather be in the broader band, but it does mean that some people are going to get a much better concert than others!

“If you are making a piece of music and you don’t know where it is going, you really have to pay attention and be alert as to where you are at that moment. Alertness is the thing that makes for excitement in art because it means you are really in the present and no other moment. You are right there with it.

“Think of any piece of art you really love and you have that sense of somebody being fully alive at the moment of doing it. Look at any square inch of a Cezanne painting and you can see the guy was really there when he was doing it. He wasn’t just filling in the colour. And I think audiences pick up on it. It is not the only thing audiences like but when they hear that they are thrilled. And nowadays it is harder to get that because most big bands are playing to a sequencer, basically. The drummer has a click in his ears, and the song is laid out because the lights are following the song and the backing vocals are keyed in at the chorus. So it is very hard for a big machine like that to change direction.”

Reickuti And Onwards

After the Brighton shows, Brian and Karl continued working together in Brian’s studio, although at first there was no plans to make an album. The process proved to be very productive, however, and in 2013 the decision was made to set aside four weeks in which a project would be recorded.

“We started off with a concept Brian called Reickuti, that had the music of Fela Kuti and Steve Reich coming together,” explains Karl. “It is music we are both really fascinated by; this cyclical, repetitive journey. When Brian played his ideas to me I started to play some guitar along with it and it just felt a really good place to be.

“That was the starting point,” adds Brian, “but we hoped it would go beyond that combination, and it has moved into something else. They are both old styles of music now but neither of them has been updated. You hear afrobeat now and it sounds exactly the same as it did in the Early 1970s when Fela started it. And it seems to me that this is one of the most potent forms of music on the planet.”

Many of the Someday World songs were built on top of rhythmic loops which Brian made over a period of years and stored away for future use. As it turns out, his methods of creating the rhythms were similar to those he used when collaborating with Talking Heads front man David Byrne on their album My Life In The Bush of Ghosts.

“The rhythms were homemade in the same way,” he confirms. “I’m not a drummer or percussionist so I construct them with modern tools, so they are probably not the kind of rhythms that drummers would usually come up with, and that was also true of My Life In The Bush of Ghosts. David and I made those rhythm tracks. It was just the two of us working on that for a long time. Similarly, Someday World comes from two people, neither of whom are drummers. But both David

For Karl, Brian’s rhythm programming was an inspiration. “I think Brian’s drumming is fantastic,” he insists. “It makes sense to me in a way that a lot of drumming doesn’t make sense. The drumming which connects with me the most is drumming from Africa, the Mediterranean, and Eastern countries. It stays the same and yet it moves around a lot, and Brian understands that, and that is part of the connect that we have on this project.”

Although Brian’s rhythms were a good starting point, the duo were still worried that they might result in rather conventional songs unless drastic measures were taken to shake things up, so they began introducing random edits to create unusual base structures on which the rest of the songs were built.

“If you want to end up somewhere different it is a good idea to start somewhere different!” insists Brian. “So we started in a different way. We’d start with a five minute rhythm track, which was maybe something that I’d done in the computer, then we found a way of making arbitrary divisions in it, often by throwing dice and things like that. We’d divide this period of time into sections and then decide that there is an A section and B section and every second section is going to be an A section, but the As and Bs are all going to be different lengths! So it means that you are forced to make complicated constructions because nothing simple will fit on top.

“It comes from a cities-on-hills idea. I have always liked cities that are built on hills because the architecture has to shift around to embrace the landscape in some way. You can’t have that kind of Mies van der Rohe, Bauhaus design because you don’t have the base to start with so it forces interesting architecture to happen. So we decided we would force it to be interesting by making the base complicated and unusual. So don’t assume a clean sheet, start with a dirty sheet of paper.”

Although Brian’s idea is a little obscure, it is shared by Karl, who provides his own example of the concept.

“Just before starting the project I spent a while in Santiago in Chile, at Pablo Neruda house,” he explains. “It is built into the side of a hill and the rooms are all like little houses, so there’s this bit of a house, then he built another room over there, then a little walkway, and a rope way and some stairs go to another room over there. And we got into this conversation about it and that developed into this fascination for cities on hills.”

Part 2 of Brian Eno and Karl Hyde: Recording Someday World, can be found here: Part 2