“Texture is a word I use a lot because I believe drama doesn’t work fully unless there is a lot of texture in there,” says Terry Molloy. “It’s the detail. It’s like looking at a canvas and seeing the brush strokes and how things have melded together. You can only get that by having different levels of age, experience, look and sound coming together.”

Terry has certainly added more than his fair share of texture to dramas over the years. In The Archers, Terry’s character, the irascible Mike Tucker, has been getting people’s backs up in the village of Ambridge for nearly four decades. Then there was Davros; the megalomaniac scientist, whose aim was to bring peace to the universe by having the Daleks he created rule over every other being. Even Davros’ voice is the texture of gravel, to say nothing of his grotesquely wrinkled skin!

Although Terry has also appeared on stage and television in countless productions, it is these two characters for which he is best know, and both are heavily, if not entirely, dependent on his distinctive voice. Davros is unable to move anything other than his mouth and one hand, and Mike Tucker, of course, is only seen in the imagination of the listener.

The Voice Of Youth

In retrospect, it seems that Terry might not have developed his voice – one which has served him very faithfully as an actor – if it wasn’t for the chosen careers of his mother and father. “Originally my mother’s side of the family came from Tyneside,” explains Terry, “but because my father was in the RAF we travelled all over the place. From the age of five I was sent to various boarding schools, apart from a two or three year stint when we went to Aden in the mid 1950s.

“I always had a facility for picking up accents wherever I went. If I spent time in Tyneside my mum would be furious because I’d come back talking broad Geordie. When I was 16 my father died and my mother settled in Bournemouth. I was studying in Liverpool so when I came back to Bournemouth they thought I was a Scouser. Then when I got back to Liverpool they’d call me a bloody Southerner!”

It was Terry’s mother who was particularly concerned about the quality of his voice, having used her own to make a living in the performing arts. Remarkably, she had left home at the age of 12 to become a dancer and singer as part of a theatre troupe on the variety circuit, eventually moving into radio broadcasting.

“Mum had a nice voice so she pushed me into elocution lessons from the age of five to ensure that I also acquired a nice voice and spoke well. One had to speak well to get on! You couldn’t have a Geordie accent or anything like that back then.”

“When we were out in Aden my mother worked for the Forces Broadcasting Corporation – the AFBA – which was the RAF radio station which broadcast to the troops. She ran a couple of programs including Listen with Mother and Children’s Hour. She was also on the mic presenting Children’s Hour and Forces and Family Favourites.

“It was around this time that the Goons were really big and we used to get the records sent out from the UK to play for the troops. Because my mum was in the station I used to listen to them before the broadcasts went out and memorise all the voices. I’d then act them out to people endlessly doing all the Goon’s characters myself.”

Despite his talent for voices, Terry’s first ambition was to become a pilot. Poor eyesight precluded that from happening, and then a failure to pass any science O-levels ruined his backup plan of becoming a vet. After taking three attempts to pass his maths exams, Terry realised that his vocation was in the arts and so he took A-levels in English, music and economics.

Next he applied to RADA, but failed to get in and instead went to Liverpool’s Christ’s College to undertake a B.Ed in music and drama. A sensible teaching career with salary grades and a decent pension was within his grasp, but Terry soon found himself more interested in becoming a musician.

“I didn’t have the ambition for teaching as such and didn’t know what I wanted, but while I was up there I got involved in a soul band. At school I had learnt clarinet up to teaching standard and played saxophone as well. I had a baritone sax and was part of a school trad jazz band that moved onto modern and mainstream jazz when our trumpet player left. I more or less perfected the glass blowers technique of circular breathing and I used that when I started playing in the soul band. I spent a lot of my time doing that. I played at the original Cavern, the Blue Angel and all the usual Liverpool venues. The Beatles had gone by then so Northern Soul was the big thing.

“I still enjoyed the drama part of the course but I suppose my ambition then was to become a professional session musician. I didn’t want to be in a superstar pop group. But I also knew that I would have to work really hard to be a good session musician so, being a lazy sod, I went into acting because I found that dead easy and there were more days off. Maybe too many days off, but I think you have to have a thirst for insecurity to take the job on in the first place!

Learning on the Job

After graduating in 1968, Terry applied for a job with a children’s theatre company in London called the Theatre Centre, reasoning that it was a good way of getting into theatre work. The organisation was run by an innovative director called Brian Way, who pioneered a new style of educational theatre.

“He wrote plays for specific age ranges,” explains Terry, “and each play included very particular tasks designed to get the children participating in the piece, instead of having them just sit and watch.

“We’d go into schools all over the country and have the children sitting around us in a circle so they were involved in the action. And it was great. It was fascinating for somebody who hadn’t ‘trained as an actor’ to be face to face with an audience of kids. If you tried to pull the wool over their eyes they knew it straight away. Truth is absolutely essential with children. And when you are nose to nose with them they will tell you exactly where you are going wrong, which is great training.

“I might have missed out by not going to drama school, but I also didn’t pick up on a lot of very bad habits that many of the drama schools encouraged. I can’t be totally specific but they each had ideologies to do with systems of acting, such as Stanislavski’s system, which is all about how you get your emotional core. You might, for example, spend all day smelling a lemon so that you can recreate the experience of smelling a lemon on stage.

“I suppose I have always gone on instinct. Peter Sellars said something which struck a chord with me. He said that what was important for him was the moment of creation – when he did something for the first time and it just gelled. Doing it again was not the same. Yes, an actor has got to learn to do it again and again and to recreate a feeling with absolute truth, but there has to be that first moment of instinctive creativity.

“What I mean is you don’t necessarily have to spend hours lying on the floor of a darkened room pretending to be a mat in order to play somebody who is downtrodden. Being in the moment and interacting with the other members of the cast, for me, is the exciting part of working on stage. You are creating and re-creating together and feeding on the information and response you get from the audience.

“And working with children was a very good environment for that interaction to happen. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it went horrendously wrong, but that was my training ground. There are actors who just want to be actors for other actors. I’ve never been one of those people. I’m not terribly happy in that environment.”

Stoke Today, Ambridge Tomorrow

In 1970, Terry began working at the Victoria Theatre in Stoke under the guidance of the late Peter Cheeseman, who championed theatre-in-the-round – a setup in which the action takes place amid the audience rather than in front of it.

“It was the same form of staging to what I had been doing with the children’s theatre and that interaction between the actors and audience was superb,” Terry insists. “It was a very dynamic and exciting creative environment. Peter worked in the same way as Joan Littlewood at Stratford, producing documentaries based on primary-source material involving people and stories from the local community.

“We did do Shaw and Shakespeare and all of that as well but Peter also nurtured a lot of new writers. People like Peter Terson, Alan Plater and Christopher Bond who wrote Sweeny Todd from which the Sondheim musical was taken.”

It was while Terry was working at the Victoria Theatre that the BBC’s head of radio drama in the Midlands, Anthony Cornish, saw him performing in a play. Recognizing an opportunity, Terry wrote to him and, in so doing, landed himself an offer of a part in a radio play in Birmingham. Soon after, Terry started work at the Midlands Arts Centre but continued getting work from Anthony Cornish. Eventually, when Tony Shryane, the then editor of The Archers, was looking for someone to play the part of Mike Tucker, Cornish, who had directed episodes of the soap, suggested they try auditioning Terry for the part.

“My audition was a scene with Dan Archer and Doris and the producers kept on asking me to bring the voice down in pitch a bit and do it slightly slower,” says Terry. “At the end they said ‘That’s fine, we’d like you to start on Monday. Your fee will be seven Guineas.’ And that was it.

“What I didn’t realise was that they had already cast the part and recorded one episode with the actor Gareth Armstrong. But after one episode he got a job elsewhere and left them with this story they wanted to run. So they decided to recast and pulled me in. Gareth actually came back into the program later as Harry Booker the postman and has played other characters too.

“What they were doing at the audition was trying to match me to Gareth, listening to what had already been recorded in the control room. He had a fairly low pitched voice relative to mine, although if you listen to old recordings of me you can hear that my vocal pitch used to be fairly high.

“They let the one episode that Gareth had done go out and then left a gap before my first episode. The listeners weren’t familiar with Mike Tucker’s voice because he was a brand new character so it was easy to feed me in as the same person.”

A Stranger in the Village

Terry’s first episode performing as Mike Tucker was recorded in December 1972 and went on air early in the New Year. By that time the soap had already been running for more than 20 years so Terry’s character was very much the new kid in the village. 40 years on and Mike Tucker is still there, having become the patriarch of his own Ambridge family. As Radio 4’s The Archers page explains, in that time he has been bankrupt, depressed and knocked down by a car, and has lost both an eye and a wife.

Playing Mike has not exactly brought Terry fame, but it has suited his ambition to become a character actor.

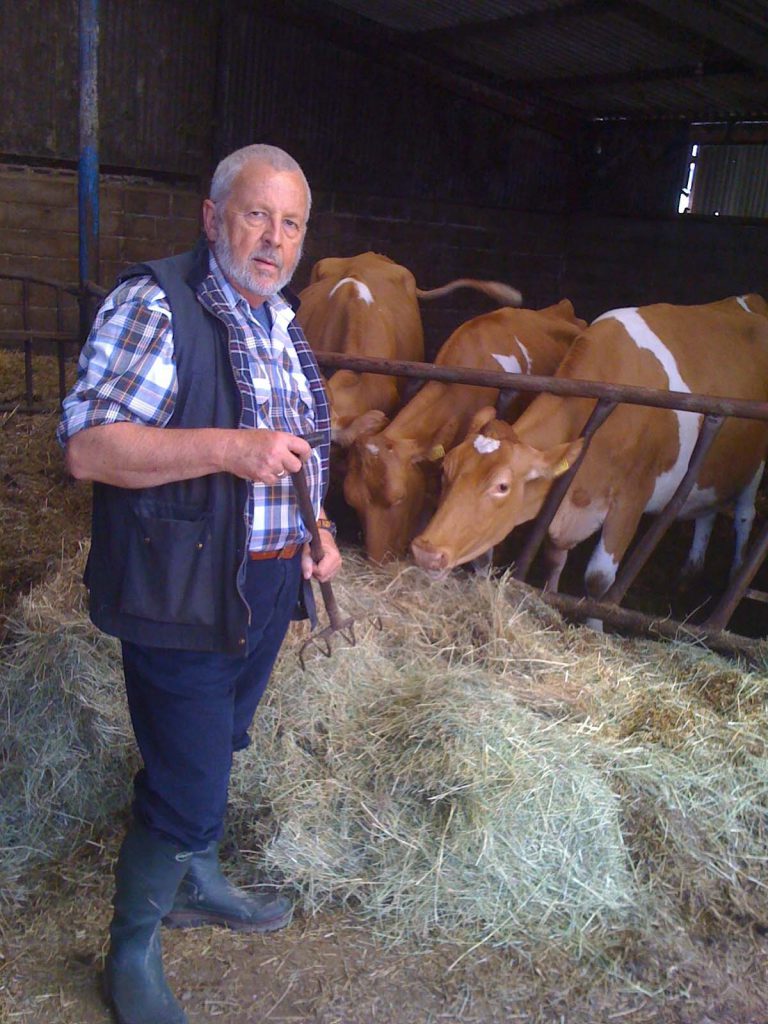

“Mum had great ambitions for me and asked if I wanted to be a star. I said that I didn’t want to be someone who waits around all year for the right scripts to come along. My acting heroes were people like Leonard Rossiter, Bernard Hepton and Ian Holm – Strong character actors who did a variety of different things. Coming into radio was the ultimate realization of that ambition because it didn’t matter what I looked like. I’m five foot six and fairly dumpy. I’m certainly not going to break any hearts visually.”

Nevertheless, the part has not given Terry the security of a regular income, which an outsider might imagine it to have done. Surprisingly, nobody on The Archers is paid a retainer, so if an actor is not featured for a while, they don’t earn any money.

“At times I’ve thought ‘Oh great, this is wonderful,’ but then suddenly you get a hiccup in bookings and hit what we call the ‘Ambridge black hole’, which is where your character suddenly stops talking and will possibly not utter a word for six to eight months. It is because the script writers are doing other stories and get locked into a cycle of using a particular set of characters. I’m not alone. Some characters haven’t spoken for years!”

“We get paid episode by episode, so if you are in an episode and only have to grunt, you get paid the same as if you had a thousand lines. I believe there are different episode rates for different tiers of actor but I have no idea – nor are we told – what those are.

“It very rarely happens, but one time on The Archers an actor got paid an episode fee just to go ‘Urghhhh’ at the end. That was when Joe Grundy got lost and was discovered collapsed in a field. But they have a budget that allows the casting of a certain number of people per episode, so it would have been accounted for.

“That’s how radio dramas usually work, which is why you sometimes find actors doubling up. If, for example, you are recording a major classic serial, the director might cast eight actors but then have each of those actors playing four or five small parts as well as their main character. Otherwise the producer would have to book and pay for many more actors.”

Not having a retainer system does have its plus points for the actors, however, as it leaves them free to take on other work, and say ‘No’ to The Archers if a great opportunity comes along. Terry explains.

“If you carried on saying ‘No’ they would eventually kill the character off or recast, as they have done with certain characters like Mike’s daughter-in-law Hayley, who was played by Lucy Davis for many years. When she started doing The Office, got well known and went off to the USA, she wasn’t available, but they still wanted to run stories featuring the character Hayley. Eventually the BBC said that if she wasn’t available they’d have to recast. She desperately wanted to carry on but that’s what happened.

“But other people like Tamsin Greig, who has been in the programme for a good 20 plus years, have managed to find a balance. She plays Debbie Aldridge, but the scriptwriters have cleverly shunted Debbie off to Hungary so whenever Tamsin gets a break from filming, theatre or whatever, they can suddenly bring Debbie back from Hungary and do a couple of episodes, should they choose to.”

Recording The Archers

Given that the Archers does not go out live on air, the recordings are made surprisingly fast, indicating just how good the actors must be. According to Terry, each 15 minute episode is allocated just two hours to record and as many as four are scheduled in a day, at 9.15, 11.30, 2.45 and 5.00. Scripts are sent to the actors so they have them four days to a week before they are due in the studio.

“We don’t normally have any communication with the director until we are there,” says Terry. “All recordings, unless they are a location special, are done in Birmingham. A set amount is paid for travel to Birmingham and my travel payments are adequate. But overnight stays in hotels are only paid if you are required for the 9.15 morning episode. I usually stay in a hotel the night before as my own expense regardless of episode start times, especially if I am in for several days running, as it is less stressful and tiring than driving back and forth to Norfolk.”

Most episodes require a great variety of spot effects, which can be anything from the rattle of a tea cup to the ambience in a room. A pub scene, for example will be backed with jukebox music, the sounds of glasses chinking, phones ringing and punters chattering. In film and television, these are mostly added in afterwards, but for The Archers the effects are played live alongside the actors by the Spot Effects Operator. “Ambience and music is also played in so we hear it all as we perform and everything is picked up by the studio mic,” reveals Terry. “When I joined it was all mono, so the actors would stand either side of the mono microphone facing each other. That was good, but now it is more difficult because we are sitting or standing alongside each other instead of being face to face, and focusing on an omni-directional stereo microphone. Working within a stereo sound picture means that you have to be very aware that you might need to speak and walk at the same time. You can’t just speak, walk, then speak again, otherwise you’ll have suddenly jumped 12 feet across the sound picture! The listener has got to picture that journey in their head.”

For Terry, one of the delights of radio drama is being able to read his part from the script and therefore not have to learn his lines beforehand. However, knowing how to turn a page without rattling the script is vitally important.

“Initially we used a special wood-pulp script paper, somewhat resembling blotting paper, which was virtually silent when handled. But that became too expensive so the BBC decided not to continue with it. Now we have a paper which is slightly heavier than standard printing paper. What you do is dog-ear the lower-right-hand corners of each page by folding them over to form a triangle for use as a lifting point.

“As you are coming to the end of the page, you lift the paper with the triangle and drop that sheet silently off the edge while you are talking. It doesn’t clatter to the floor because is stapled to the rest of the script, which you keep held in the other hand. Then you are on the next page. When you come to the end of that page you flip it over and you’ve got another one!

As for mistakes, Terry admits that the actors do still make them all the time.

“You just go back and do it again. In the olden days they used to record on wax disks and if the actors made a mistake they had to record a new disk. Then it went to reel-to-reel, and the tape would be sliced and spliced together in the edit suite. Now it is all done digitally and they can remove intakes of breath, slight coughs or extraneous shuffling, without us having to worry about it.”

What’s in a Voice?

Although it is impossible to know what the casting team wanted back in 1972 when they were looking for actors to play Mike Tucker, they obviously had a certain quality of voice in mind. Indeed, Anthony Cornish might never have considered recommending Terry if Gareth Armstrong’s voice and delivery had not been similar in some way.

“Actors can be fairly interchangeable, so it’s the quality of the voice as much as anything they are looking for,” says Terry. “They’ll be looking for an aural range in the sound picture from within which the characters are going to emerge. But they will also be concerned about getting right the balance of aural ranges within a piece. Otherwise you could end up with four male voices all sounding the same and the listener would be unable to distinguish the characters. So you have got to get a balance of age, experience, lightness, darkness, or whatever it might be, to delineate the various characters.

“A film producer will have a specific visual image in his head; a radio producer will have aural image which creates a visual image within the head of the listener. Everyone’s visual image is going to be different but the director knows the effect he wants from certain characters, having worked with the writer when developing the script. He will want a certain quality of voice for a particular character and will go to the bank of actors he uses or has seen to find someone suitable.”

Radio Days

Having worked in Radio for four decades, Terry has seen many changes. Naturally, as an actor, it is drama which he is particularly concerned about. “Radio drama has diminished over the last 20 years. There used to be a lot more slots within the scheduling for drama, but those days will not come again. Before control was centralized in London there were busy departments for drama in Manchester, Bristol, Leeds, Birmingham and London and they ran their own budgets and commissioned their own writers. They fed product into the national radio network and so there was a lot of different writing making it a much more complex and textured service.

“There was more of a sense of freedom then and directors were ready to take chances. Now decisions are made by commissioning editors, committees, accountants and focus groups, with managers looking over director’s shoulders and saying ‘That won’t work, you have to do it this way.’ But statistics kill creativity because people become scared to do things which don’t fit with the current thinking or statistical analysis.”

In terms of quality control, Terry also feels that cost saving has had a detrimental effect in some areas, and highlights the plight of the BBC’s pronunciation unit as an example of this.

“Everyone at the BBC had free access to the pronunciation unit so if they had a problem with a word that was coming up in a program, be it a news bulletin or whatever, they could ring up the unit and someone there would explain how the word should be pronounced.

“But management changes meant everything had to be accounted and paid for, so every time a producer called for a pronunciation it got charged to their programme budget. Producers working with tight budgets became reluctant to call up and, as a result, mistakes were made.”

But Terry has also recognised some changes which have been beneficial, particularly to The Archers, and once again, it relates to texture. “When I joined they didn’t have children speaking. There would be crying baby spot effects, or occasionally Judy Bennett, who plays Shula, did children’s voices. But usually nobody actually spoke in Ambridge until they were over the age of 18. They were always silent or upstairs playing games.

“Now they bring in child actors and feed into the storylines, which is key to the success of the programme. Mrs. Dale’s Diary stopped because there was no generational line of children to carry the story through. Once Dr Dale and Mrs. Dale had died – no diary! The Archers, on the other hand, has had another generation sitting in the wings or being brought forward to take over. Because of that there are now well over 60 members of cast, whereas when I started there were just 23 of us.” TF