In Part 1, Graham discussed his career up to and including the start of his Church Mice series of books. In Part 2 he speaks in depth about his techniques, thoughts and plans for the future.

Part Of The Process

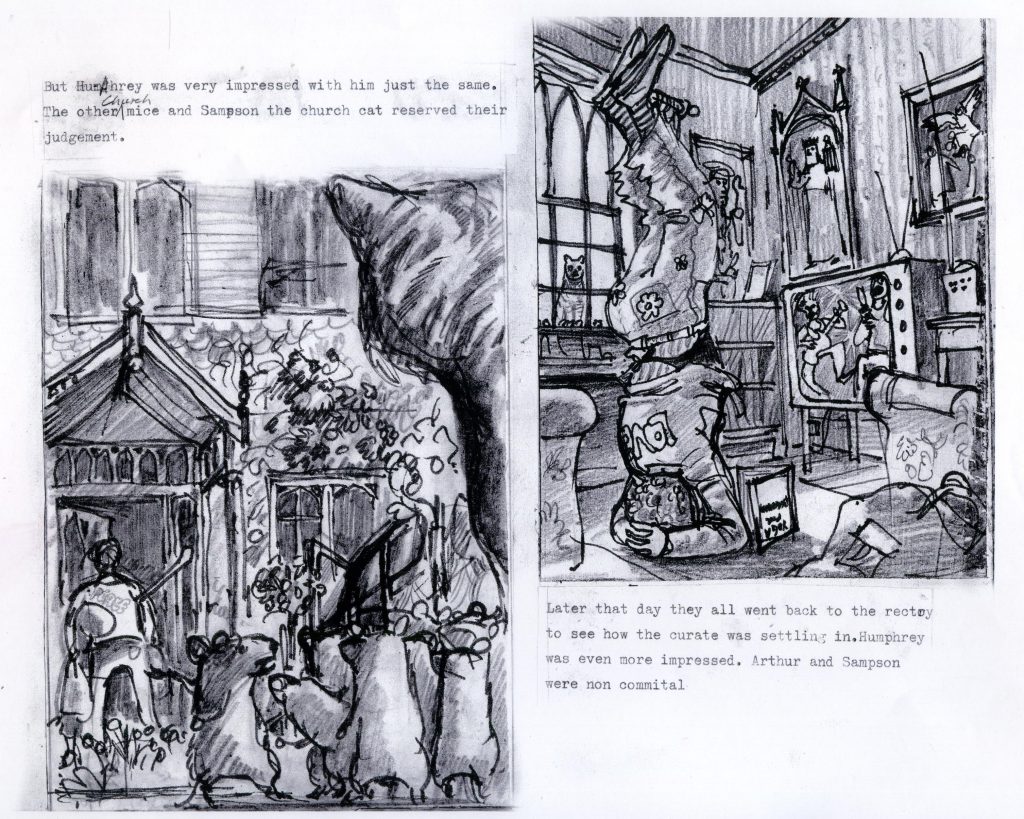

Before Graham began work on his first book, The Church Mouse, he had to provide his publisher with a rough version so that they could get an idea of what the finished product might look like. It was a practice he continued throughout the Church Mice series. Graham explains the steps he took.

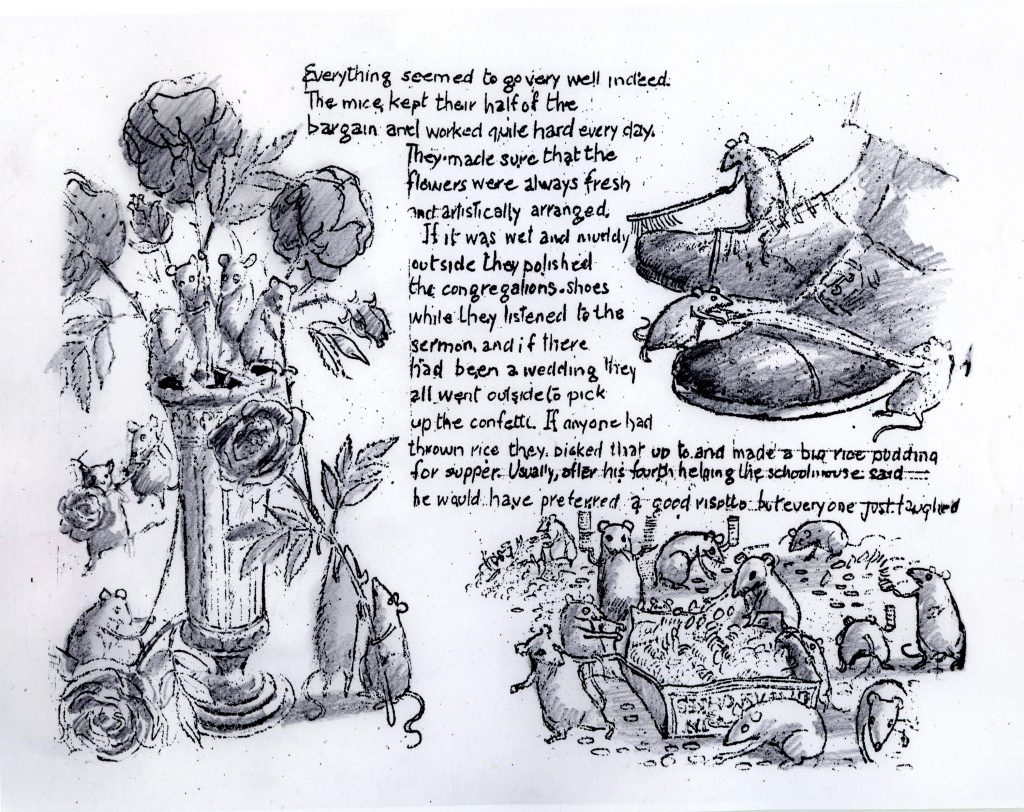

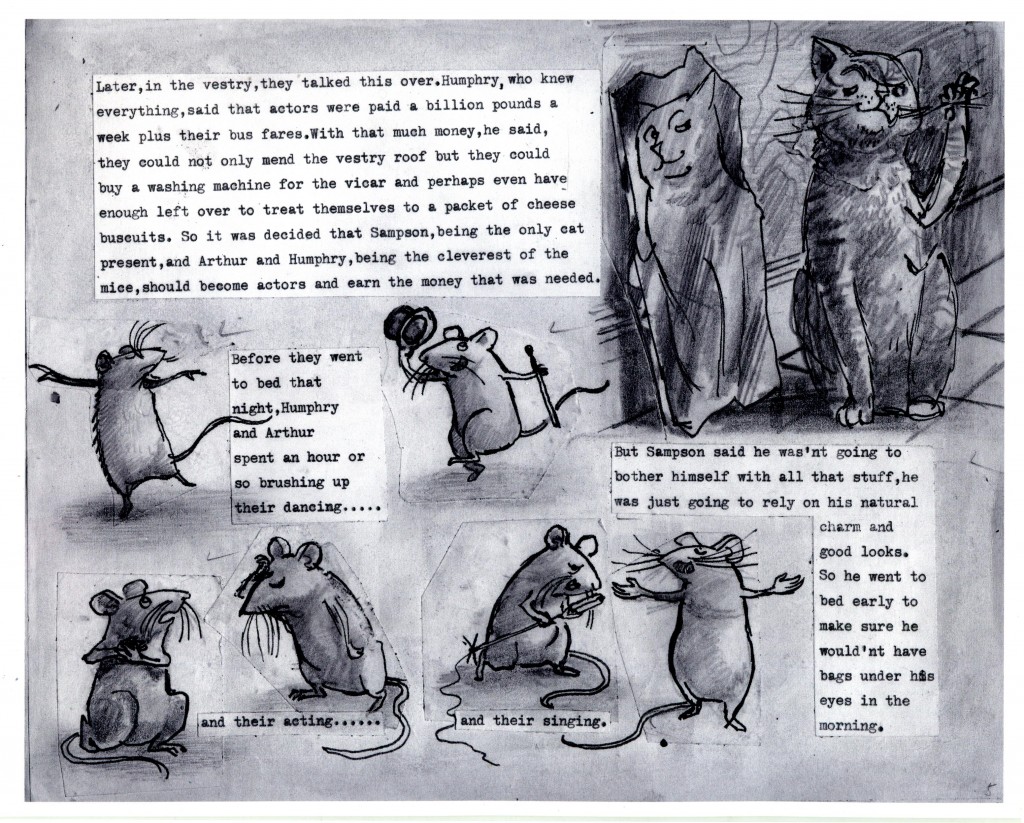

“The normal thing is you produce a dummy first, which is exactly the same format as the finished book, but done by hand. Once I’d thought of the story I could do a dummy in two or three weeks, if the working was very rough. But it usually took me a full six months to do the finished book.

“In those pre-computer days I used an ordinary typewriter to indicate the type on the dummy, and did rough sketches, mostly in black and white, to show what the picture would be like. Then I’d paste it together to look virtually as the page would be, and bound it in book form simply by sticking the loose leaves together with tape. The book length was restricted to 32 pages, so if the story needed more scenes I’d fit several pictures on a page. Then it had to be approved by several people who all wanted to make alterations and suggestions which I normally wouldn’t take any notice of! Once you get that approved you can start the finished artwork.

“A lot of artists work half up. When it is half up you don’t actually reduce it by half for printing, you reduce by a third. But I work at SS – same size – because I like to see that what I am doing is what it is going to look like when printed. You get more of an idea of what you can get in if you work same size. I have tried working half-up, but what I do doesn’t seem to look very good when it is reduced. As one’s eyesight tends to get worse, I suppose in time I’ll be compelled to work half up, but I don’t need to quite yet.

“If I thought the rough was good enough, I would square it up by putting one-inch squares all over it so that I could make an accurate copy. Then I would start a new pencil drawing referencing from the squared-up original. So if, for example, I had sketched a face in rough, I would copy the rough but add more detail.”

Once Graham had completed his pencil outlines for the finished artwork, he went over them using Indian ink, thereby creating a line drawing. To colour in he used a selection of coloured inks which he diluted with water and painted on with a brush.

“The ink line would still be visible, so they were essentially line and wash drawings,” says Graham. “The problem with ink is that once it is dry you can’t move it or do a thing with it. I developed a dodge in the end, using a paper which used to be called CS10, made by Colyer & Southey, who are now defunct. It had almost an enamel-like surface, which you could scrape off. So if you made a bad blunder with the ink, you could get a razor blade and actually scrape the top layer away without destroying the surface. It was even possible to do it two or three times, but after that you got through the enamel-like surface down to the board underneath. You’d had it then because it was yellow and just bled when you tried to paint on it. But at least it gave you a few chances!

“Indian inks have a cleanness and clarity to them, but they also have the rather unfortunate characteristic of fading in sunlight. I sell my originals and I’ve sold virtually all the Church Mouse drawings, but you have to warn anybody who buys them not to expose them to sunlight.

“The inks also had a slight sheen and tended to reflect the light, and printers hated that. They could overcome the problem easily because virtually every artist was using inks back then. But despite the dislike printers had for them, they did reproduce very well.

“The printers could reproduce more or less any colour you painted, so there weren’t really restrictions, but there are certain colours they found hard to match, particularly the very bright ones. Purples somehow don’t seem to come out very well either, but it’s pretty good when you think that in printing virtually every colour is made from cyan, magenta, yellow and black. These days they can do virtually anything and if they are prepared to spend the money. They will add a separate plate for a colour which is hard to get just by mixing the three primaries.

“I think that The Church Mice At Bay, with the swinging vicar, was the first book I did using watercolour paint which, unlike the ink, you can wipe off if you make a mistake. From then on I started laying down the washes first and painting in the line work afterwards.

“All the Church Mice books, with a few exceptions, were done with either transparent ink or water colour, but I now use opaque body-colour paint which requires less skill because if you make a mistake you can just paint over the top of it. For body colour I use gouache which is basically watercolour containing Chinese white to make it opaque. I didn’t really use gouache until the last couple of Church Mice books.

“These days I work on top of the dummy, so I don’t really do roughs any more. What I sometimes do, if I feel a thing is not going well and starts looking a bit overworked, is make computer print of it and then paint over the computer print, rather than do the whole thing again. I just don’t have the patience for that anymore.”

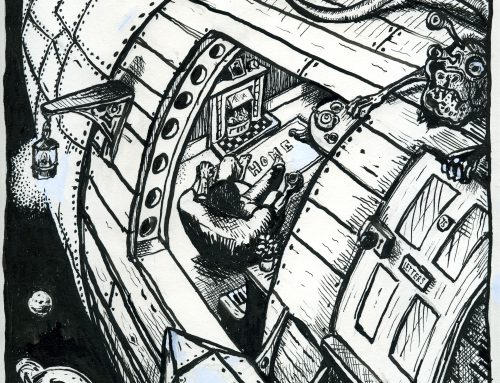

Getting Perspective

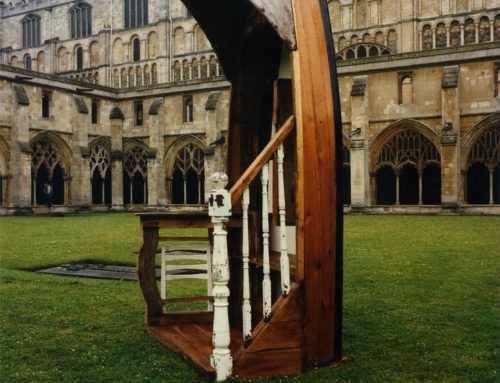

Even very successful illustrators seem to struggle to get perspective right, particularly when their pictures are composite images taken from several sketches, each with a different angle of view. It is also common for illustrators who work in a realistic (rather than cartoonish), style to come unstuck when dealing with anatomical proportions. Graham’s pictures, however, are drafted incredibly well. Even when the view is from an awkward position he could only have imagined, it usually has impeccable perspective. Rooms, buildings and scenes are pictured from above, below and the side so convincingly that looking from one to another is almost like walking around the scenery.

“I think that is to do with having an interest in cinema and being a scenery designer for 15 years, or much longer if you include my repertory years,” explains Graham. “Most artists have something which comes fairly naturally to them. I always found that fairly realistic drawing and scenes came naturally to me.

“It’s partly imagination, but also one remembers bits of one’s own hometown. And then you find photographs and piece it together. My little town, where all the Church Mice stories take place, looks as though it is carefully planned, but if you study it very carefully you’ll see that I’ve often had to alter things from story to story in the hope that people would forget what it was like in the last one! Occasionally I have had letters from children pointing out that one street doesn’t lead into another street anymore.”

As for Graham’s anatomically accurate, but very dynamic and entertaining, rendering of people and animals, he does not, as one might expect, prepare with endless sketches from life.

“Being pretty idle I tend to use photographs. All the time I’ve been an illustrator I’ve collected cuttings and photographs clipped out of magazines. Most artists do this, particularly illustrators, because you never know what you are going to have to draw. I now have pretty comprehensive files of clippings and books, so I have some sort of reference for virtually anything I’d ever want to draw.”

One of Graham’s greatest artistic feats is making his mice look anatomically correct, but have them walking and running about on their hind legs at the same time. One would imagine that this is something no reference library of photographs could help with, but Graham is quick to play down his skill.

“Artists have always done mice walking around on their hind legs, like in Beatrix Potter. My mice are fairly anatomically accurate because I have lots of photographs of mice and when I was living in Kellaways Mill I was over run by them. I think I did draw the mice, and particularly the cat, a lot better in the later books. I’m not too happy about the way I drew the cat in some of the early ones and I made the mice’s noses too long in the first book. I shortened their noses a great deal later on and so they became more anatomically correct as the books progressed.”

“But what I have never done is put them in clothes. For some reason I just couldn’t accept the idea of them wearing clothes. Their fur is their clothes so to me it somehow seemed extremely unhealthy for them to be dressed. I only did it once and that was in Humphrey Hits the Jackpot where Humphrey wins the lottery and decides to buy himself a suit, but he doesn’t stay in it long.

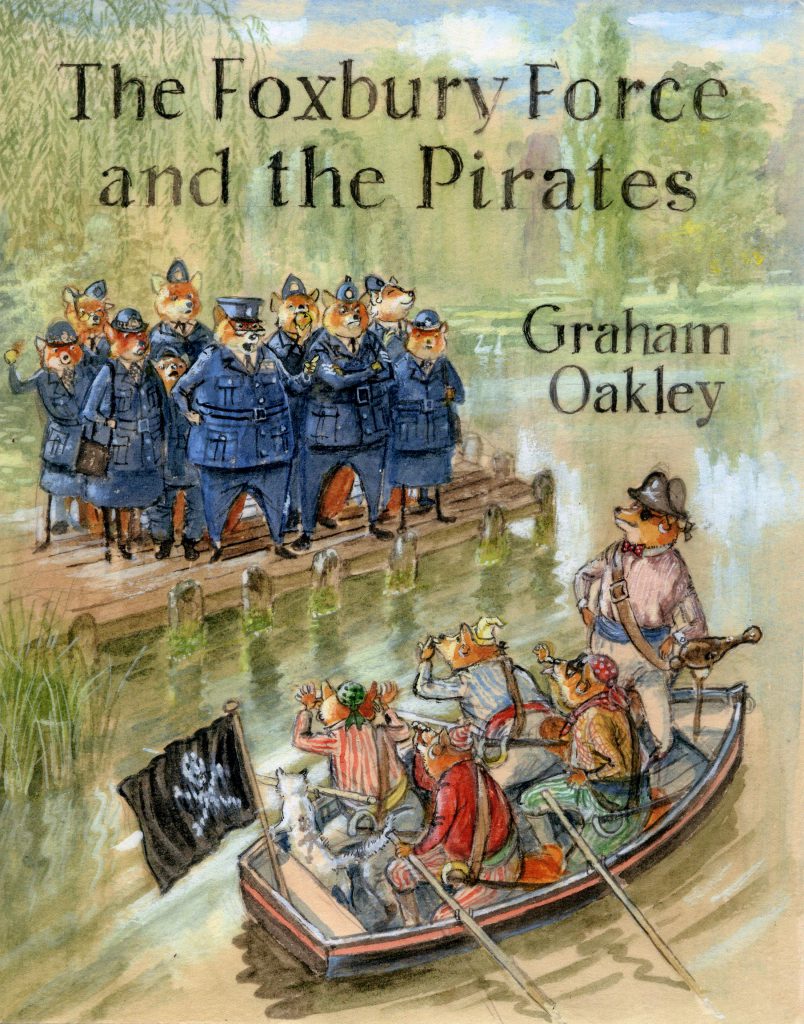

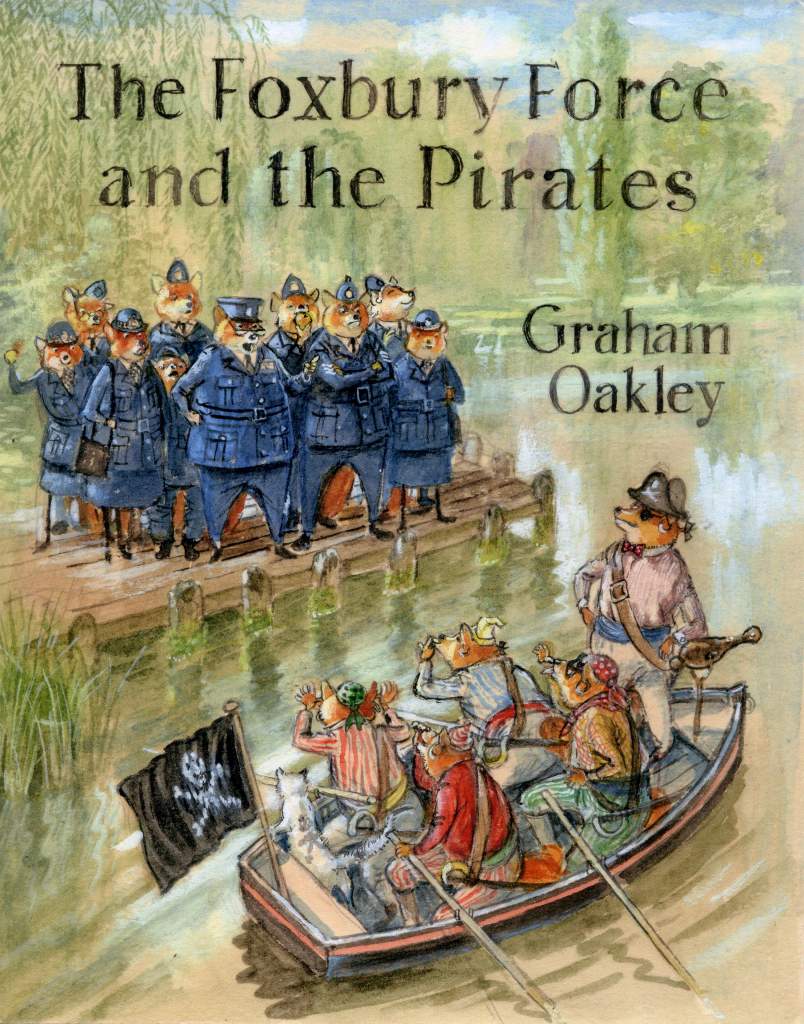

“Having said that, I did do another series called the Foxbury Force about foxes and I clothed them because they are supposed to be a police force in uniforms. I was never really happy about putting clothes on them but the public didn’t like the books anyway. I don’t think the publishers lost out but there was no enthusiasm for the series so I only got as far as doing three. If the public had liked it I’d have written some more and kept on putting them in clothes but there was no point flogging a dead horse.

“My publisher had persuaded me to try and think of another series and all I could come up with was foxes. I personally think the illustrations in them are better than The Church Mice books but it doesn’t matter what I think, it’s what the people who might be buying them think that matters.”

The politics Of The Church Mice

Graham’s book note at the end of The Church Mouse explains that, although he had already illustrated many books for children, this was the first he’d done entirely on his own, doing it his way. The words hint that Graham might not have enjoyed illustrating the stories of other people and, as it turns out, that is indeed the case.

“Though I am not by any means a natural writer – writing comes extremely difficult to me – I really don’t like illustrating other people’s stories. Very often, because you are illustrating something done by a writer who’s talent is for writing, there is no need to illustrate it at all because they’ve done it all in words. But when you write it yourself you can create humour by making the pictures contradict the text.

“It’s really quite good fun doing that but you could never do it if you were working as an illustrator on someone else’s book, and that’s really why I took to writing my own.”

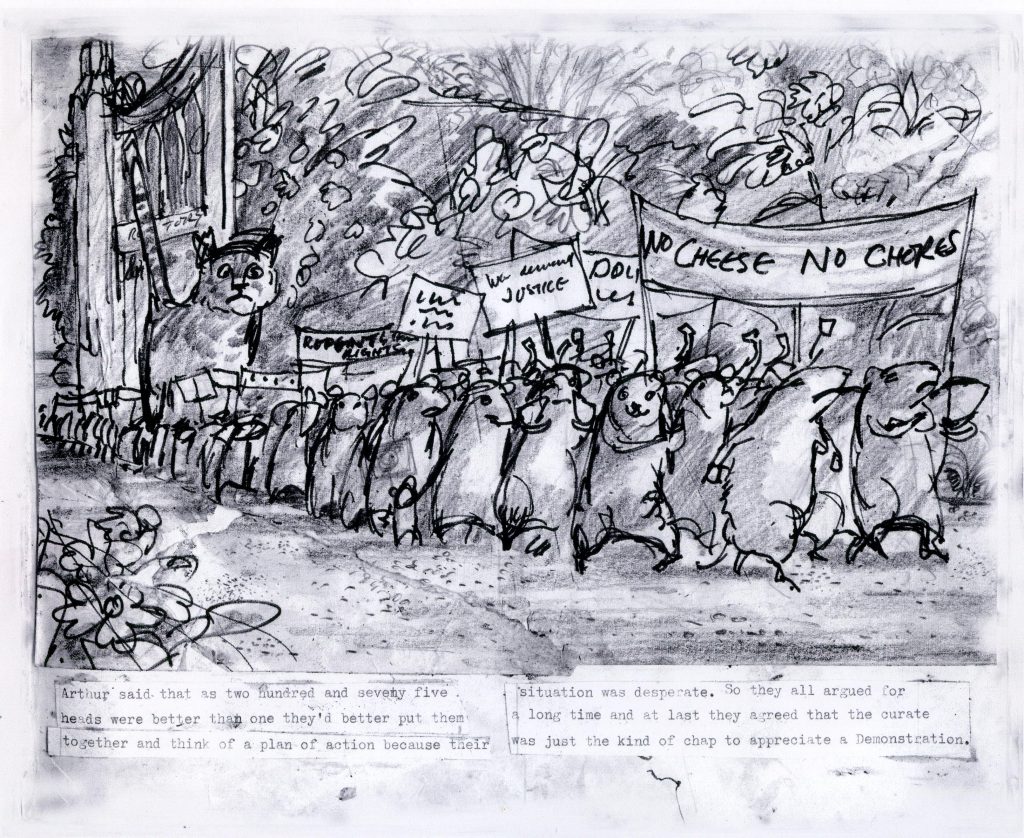

Not content with simply playing the text off against the pictures, Graham introduces other layers of meaning into his work. Every gravestone, wall plaque, signpost and notice board tells a little sub-story of its own, as if left there to treat anyone who has taken the time to look more closely at the detail. Then there are the little comedy dramas taking place within the mice families. Such details are not necessarily anything to do with the main story and play out in the background.

“If you were illustrating someone else’s book they would want to write whatever went on the grave stone and wouldn’t want the illustrator doing it. As for the mice, I only ever named three of them, but it’s like an opera with three leading characters and the rest are the chorus.

“I wonder why more illustrators don’t do their own books. I suppose it is because most books are commissioned, so if you invent a book yourself, you still have to persuade somebody to publish it. Normally the writer has done that bit already.”

One other theme running though Graham’s books is the lack of care people have for their environment. The aforementioned trendy vicar, for example, defaces his church with hippy paintings and shatters the peace; beautiful buildings are gleefully smashed to make way for hideous architectural tower blocks; and piles of litter gather on the streets and under the church pews.

“I’ve noticed with litter, that very often there is a bin nearby but none of the litter is in it,” explains Graham. “That’s a pretty common sight in English towns, I think. And I’ve done the jokes like the crumpled and thrown away newspaper, where the one bit of headline you can see is about how the town is litter free.

“I also feel really strongly about the way towns are being ruined and all made to look exactly the same. We are certainly more conscious of heritage than we were in the forties and fifties. Nothing was sacred. That was the era when they knocked down old houses to make way for huge tower blocks, which are now being demolished themselves. At last it has occurred to town planners that people don’t like living in them.

“But it still goes on. In Lyme Regis we had a Woolworths which closed down and has been taken over by Tesco. There were demonstrations to try and prevent it but they didn’t stand a chance. The council wanted it here because of the rents they were going to get, and so it’s here.

“And we’ve got an old pub called The Three Cups at which people like J.R.R. Tolkien, Jane Austen, G.K. Chesterton and Tennyson used to stay, and its been closed for donkey’s years because the brewery wanted to turn it into flats.

“We’ve had demonstrations but they’ve now got permission to do it. Even Dorchester council, are trying to save costs by closing 15 libraries, including the one in Lyme Regis, and yet they’re spending a fortune building themselves new council offices.”

The Future

Although Graham is now many years past the official retirement age, he has not given up working and seems unlikely to ever do so. Nevertheless the question as to whether or not he should carry on trying to get work published is one which he is still thinking about. “I think it is time I hung up my boots, or whatever the term is,” he says in one breath, reflecting on his lack of success finding a publisher for his latest work.

Then, in the next breath, Graham starts talking about having another go! “I have just done my version of Beauty and the Beast which publishers don’t like at all, but I’m quite interested in self-publishing. I might have a go but I’ve not priced it. I imagine it doesn’t come cheap, but you wouldn’t have to sell in great numbers, unlike a commercially produce book which has to pay for the building, staff and so on. Certainly if I was young again at this point I wouldn’t bother with publishers at all. I would go in for self-publishing. For anyone who is really prepared to put their back into it, who is a good illustrator and writer, self-publishing is the thing.”

Despite the lack of publisher interest in Graham’s current output, his back catalogue is still in demand and represents a relatively safe bet for profit conscious publishers. Thus, the UK children’s book publisher Templar has been slowly re-issuing his Church Mice series.

“Some people at Templar did suggest that I do a new one in the series,” says Graham, “but it’s something I did years ago and I don’t think I could again. It was fun doing them but I now do fairly realistic stuff mainly with human beings rather than animals. Templar have got as far as re-issuing the forth book. I’m not sure if the colour is as good but they are beautifully laid out and they are extremely well produced books. There is obviously a demand and it’s interesting to see that the original first editions go for anything up $100 on e-bay.”

As for Graham’s own preference, he admits to having a soft spot for four books of his, none of which formed part of the Church Mice series.

“None of them are in print now, but I think some are the best things I ever did. There was one called Henry’s Quest, which still gets a certain amount of interest. Another was called Hetty and Harriet, about two chickens. Then I did one called Magical Changes which had split pages that you reshuffled to make up to about 500 different pictures. That one is still in print in France. And there’s another called Once Upon A Time: A Prince’s Fantastic Journey, which I think included some of the best artwork I’ve done.”

Long may he continue. TF

Graham’s web site is: www.grahamoakley.co.uk

Part 1 can be found here: Part 1