The manor house in Cambridgeshire’s Hemingford Grey was made famous by children’s book author Lucy M. Boston, who lived there for over 50 years. Lucy based her hugely successful series of Green Knowe books on the garden, house and its contents, seamlessly blending the real location with the fantasies of her stories. Today, the house is run by Lucy’s daughter-in-law, Diana Boston, who opens her doors to the public. Diana explains what it’s like running one of England’s most iconic homes.

Diana Boston at the Manor

“Somebody asked me the other day whether or not I would give up doing this if I won the 161 million pound European Lottery,” says Diana Boston, resident and owner of the manor in Hemingford Grey. “Actually, I don’t think I’d give up showing people around the house because there is something very self-indulgent in magicing people. Whether they are sulky teenagers who have been dragged here and can’t think why they are coming, and think it’s un-cool to go round a place like this, or people who are passionate about the books; they all get magiced in the end.”

There is certainly something fascinating about the manor. Many people visit to experience a place they imagined as a child after reading Lucy Boston’s Green Knowe books and studying their illustrations, which were lovingly drawn by her only son, Peter. Far from being a reconstruction in a theme park or an uninhabited museum, the house is first and foremost a home – a characteristic which only adds to its appeal.

For those interested in horticulture the gardens are magnificent, and notable for the chess-piece-shaped topiary which features heavily in the Green Knowe stories. As for the house, it dates back so many centuries that even Lucy Boston’s 50 year tenancy seems brief in comparison. The original building, some of which still forms part of the inner structure of the house, is known to have existed in 1130. However, when Lucy bought the manor in 1939, she found it had been badly renovated, and immediately embarked on a project to have it sympathetically restored.

By the mid 1950s the house was being described by Lucy and sketched by her son Peter, thus the public’s fascination with the place began. Lucy carried on writing and living in the house until she died in 1990, aged 97. It was then that her daughter-in-law, Diana, found herself taking over responsibility for the manor’s upkeep – a job which has proved to be both a burden and a privilege.

The Manor, as seen from near the river Ouse

Strange Paths

The manor, in the eyes of many, is the quintessential English home. Curious, then, that its current resident was born and brought up in Kenya, over 4000 miles away. Diana attended school in Kenya up to the age of 17, only moving to the UK so that she could train to become a primary school teacher.

“I came over here in 1957 to do a teacher training course at the Froebel Educational Institute in Roehampton,” say Diana, “and I discovered the Green Knowe books when I was doing my course. We were given a list of books to have in our classroom and a friend of mine, who was doing nursery training, wanted to see what books were on my list. She leant over and said, “Have you ever read Lucy M. Boston?” And I said “No, I’ve never heard of her.” She said, ��?Well, I think you’ll enjoy them,” so I read the only two that were available at the time and thought, “Wow!

“Lucy didn’t write down to children and that was the same of all that generation of writers. CJ Lewis was a bit before Lucy, but Philippa Pearce, although younger, was very much of the same time. They didn’t write down to children and that’s why all those books were on this list that I was given at college. The books were used to develop children’s use of language and imagination, and Lucy does write very well, there’s absolutely no doubt about it. A Stranger at Green Knowe, for example, won the Carnegie Medal in 1961.”

After her course, Diana began teaching in London, and married a Royal naval officer called Peter Robertson. Four years into their marriage, in December 1965, Peter tragically lost his life when his ship, the HMS Bastion, went to the aid of an Iranian dhow and Peter entered the water in order to rescue the survivors. Diana and Peter’s children, Charles and Andrew were just 6 weeks and 19 months old at the time.

“He lost his life saving three people from drowning in a storm in the Persian Gulf,” explains Diana. “He already had a survivor under each arm and was taking them back to the life raft when a third grabbed hold of Peter’s life jacket thereby pushing him under the water. The sea was so stormy that the man on the life raft lost Peter’s lifeline and couldn’t pull him in. He was posthumously awarded the Albert Medal and I think was the last person to whom it was awarded before it got amalgamated with the George Cross.

“When I married again it was to Peter Boston, so I’ve come quite a long way round to get here.”

Meet the Bostons

At the time of his death, Peter Robertson was based at the Royal Naval Air Station Culdrose in Cornwall, so Diana and the two boys were living nearby. As chance would have it, Lucy Boston’s nephew and niece were Diana’s next door neighbours and Lucy often made the trip from Cambridgeshire to stay with them. “Lucy was very fond of her niece and nephew,” says Diana. “I met her because she was staying with my neighbours and I was invited over to a meal. I was very excited to meet the author of the Green Knowe books. It was after that trip that she wrote a wonderful book called The Sea Egg, which unfortunately is out of print at the moment. I met Peter the same way really; when he came to stay with them. I first visited the Manor when Peter and I got engaged and we came to tell Lucy the news. We got married in ’67, and lived happily ever after, as they say.”

While looking for a suitable property to do up, the couple moved to Watford, before eventually finding an old mill in the Hertfordshire village of Ashwell, less than an hour’s drive from the Manor in Hemingford Grey. Diana’s two sons, Andrew and Charles, were too young to know anything about the Green Knowe books when they made their first visit to the Manor, but understandably found it quite an adventure.

“Once we had moved up from Cornwall to within visiting distance we used to come over here a lot to see her. And it was quite something to bring two littlies into this house with everything perfect. Of course, they wanted to look at everything, so I spent quite a lot of time being the buffer state between Lucy, the house and my children. Possibly too much so, but then one is: I was coming into a new relationship so obviously that’s quite tricky. The youngest one, Charles, was 2 and Andrew was three-and-a-half, so to them the manor was just a place to be explored.

“Later they read the books and were very keen on them. I remember my youngest son standing in the flower beds while Lucy was pruning the roses, and he was telling her the stories as if she had never read them. It seemed to me that that he was telling her what had happened and they were discussing them. I think she had forgotten that she’d written some of the things she had.

“They had quite a close relationship; close enough that when he was asked what he would like for his birthday he said he wanted a story written about a fossil snake and she did write one called The Fossil Snake.”

“But we weren’t involved in the running of the house at all. Lucy was living here, gardening and still writing and Peter was illustrating her books. We didn’t do anything for the house, apart from maybe occasionally pulling the odd weed.”

Looking down from the attic stairs. This is a view of the upstairs hall, which was used during World War II by Lucy Boston to give gramophone record recitals twice a week to the RAF. The EMG gramophone dates from 1929

Architecturally Speaking

By the time Diana and her children were introduced to the Manor, Lucy had been living there for 30 years on her own. She took possession of the house on 31 May 1939, and almost immediately embarked on a restoration project. A few years before, in the mid 1930s, Peter Boston had a place at Kings College in Cambridge, studying engineering, but later switched to architecture. It seems likely that, given his area of interest, he might have had a lot to do with the renovation had it not been for his service with the Royal Engineers during the war. By the time Peter was able to continue his studies, the ever independent Lucy had the place very much the way she wanted it.

“After the break-up of her marriage to Harold Boston in 1935, Lucy went to both Florence and Vienna,” say Diana, explaining the event which led to Lucy settling in Hemingford. “She came back from Vienna when it seemed as if war would break out but I’m not sure of the date. At that time Peter was studying at Kings and she took lodgings in Cambridge, just by King’s. From her window she was more or less able to watch his comings and goings!

“In her autobiography she says she bought the house in 1937, but according to the deeds it was 1939. By the time she wrote that I think she felt as if she had been at the Manor a long time! She’d actually seen it 25 years before and always thought that it looked very tranquil in its field beside the river and often thought of it in the intervening years. Then when someone told her that there was a house in Hemingford for sale, she immediately thought of this one and came out in a taxi to see. The only traffic she passed on the road, which is now the busy A14, was a man and a horse!

“The whole house was restored back to being as near as possible to the Norman part from 1939 through to1941. Of course, Peter was off with the war when all that was going on. When he was back he would come and stay and his name appears occasionally at the gramophone recital records as one of the people who were there that evening.

“The architect who helped Lucy was Hugh Hughes. Peter did one or two things like uncovering the fireplace in the dining room, where Lucy wrote her books and sewed her patchworks. He was convinced that there was a big inglenook fireplace there but they had had an expert in to see if there was one and she poked around and thought there wasn’t. Then when Lucy was out Peter took a pickaxe to it and, luckily, found there was, because I don’t think Lucy would have been too pleased otherwise!”

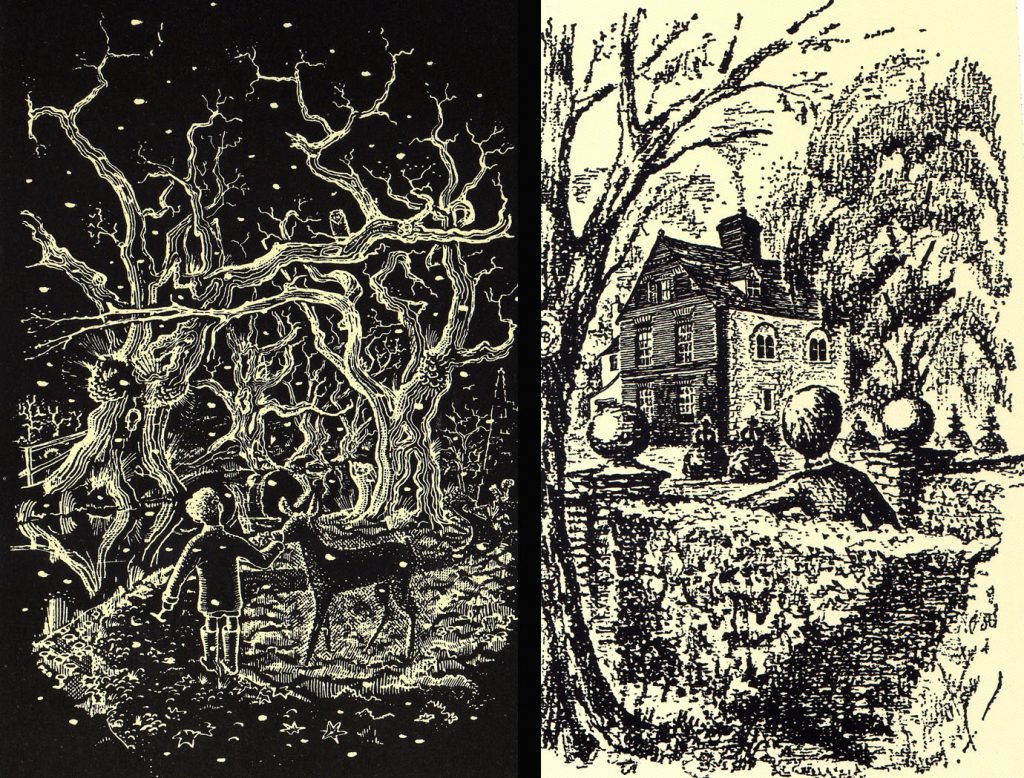

Despite missing out on the renovation of the Manor, Peter’s illustrations suggest that he still managed to develop a deep and intimate relationship with the house and garden. There can be little doubt that the Green Knowe most readers picture in their heads is one based on the detailed ink drawings Peter made for most of Lucy’s books. Indeed, it is striking how similar the drawings are to the house and gardens which can be seen today – the house remaining very much the same since its renovation. The first book in the series, The Children of Green Knowe, has remained in print since it was first published in 1954, but has experienced a number of edition changes which affected the production of some of Peter’s drawings. Diana explains how the drawings were done from edition to edition.

“The first edition of The Children of Green Knowe was a hardback published by Faber & Faber and it contained eight large illustrations done in pen and ink on white board. Those dark, whole-page illustrations were drawn in negative, photographed and the negative was then used for printing. Peter’s written instructions were ‘Reverse and print white on black to cover full page. Black to bleed off all round.’ He wanted the pictures to bleed off the page but that meant those eight illustrations couldn’t be printed at the same time as the text. They had to be printed separately, guillotined and tipped in, which is when they are stuck in by hand!

“Faber wouldn’t allow him to do any more like that as it was hugely expensive so he used scraperboard for most of the rest of the books. Using a scraper board and having margins solves the problem of having to hand stick the pictures.

“So when Faber & Faber published the paperback edition of The Children of Green Knowe the eight large illustrations were omitted. For the Puffin edition of The Children, the large illustrations were changed by Peter to be much whiter, as the quality of the paper used by Puffin was poor and would have absorbed all the fine white lines.

“Faber & Faber then got the rights of The Children back from Puffin and went back to using the original large illustrations with good quality paper, but gave them a white margin which meant that these illustrations did not have to be printed separately. This is the edition that is currently in print! The illustrations for all the other books stayed the same, no matter what the edition was.”

Peter’s illustrations. Diana “The Green Dear was from The Children of Green Knowe so drawn in negative. Roger at the Gate was a pen and ink drawing, as far as I remember. The jacket illustrations were paintings.”

Taking Over the Manor

After their move to the mill in Ashewell, Diana took up a teaching post in Cambridge while Peter joined an architectural practice based in the local area. The family continued to visit Lucy over the following 20 years, but still had little to do with the running of the manor. Lucy remained very independent, right up until the late 1980s, by which time she was in her mid ’90s.

When, finally, Lucy became too frail to entirely fend for herself, Diana found herself gradually becoming more and more involved in life at the Manor.

“She died when she was 97 so obviously there were a few years when she didn’t necessarily cook for herself and I used to either cook or buy one-person meals and fill her fridge and little freezer compartment. I was teaching in Cambridge at the time so I used to come over, maybe once a week, and stay the night.

“We were worried about her living on her own in this freezing house, I mean it is freezing cold and one day she threw a log onto the big open fire and nearly threw herself onto it as well. She decided then that it was dangerous to have the fire and so she just got ever bigger electric heaters. Her electricity bill in the winter was something like £700 a quarter, which really was a lot then.

“We were so worried that we suggested we should come and live here. She thought about it for a bit and said, “You know, it’s a lovely idea but I think it will get in the way of my social life,” and she was then 95 so she actually didn’t want us here. She wanted her independence and to go on. I think we put our heads in the sand and hoped she was immortal. We never imagined that she would die.”

“But when she died we had to jump around fairly quickly. She had borrowed from the bank against the house in order to keep all this going, and it is huge. And of course the older you get the less you can do, so it becomes more expensive to keep a place like this. You have to pay other people to do what you’ve always done.

“It was at a time when the bank interest was something like 15 percent, so her borrowing loan was known in the family as the black hole – any money just went straight into it. The interest was like one of those awful problems that you are given at school – somebody is falling out of an aeroplane and going faster and faster as he heads towards the ground – well, the bank loan was something a bit like that. It just got bigger and bigger and bigger. The bank had been making a fuss because they didn’t like lending over £75,000 and the interest coming in the whole time was adding to the debt so we had to jump around very quickly.

“I had been teaching full-time at St John’s College School in Cambridge but gave in my notice when Lucy had a stroke and it was obvious that she would die. I knew that something would have to be done about the house and whatever we chose to do would take my undivided attention. Peter was working full-time so it would be up to me to do whatever we decided. I took to running it and opened it up to the public. At first I didn’t properly move in. I never knew whether I was going to wake up at our house in Ashwell or here in the morning. The idea was to try quickly to get it to earn its keep, and we’ve just gone on doing that, really.”

The bedroom on the first floor

Mill or Manor

One thing Peter and Diana could have done to help clear the debts was sell the Ashwell mill in which they lived and then move the family, which by that time also included daughters Kate and Harriet. But despite the Manor’s obvious charm, the decision was not an easy one to make.

“Peter was lucky,” explains Diana, “architects don’t often get to do their own houses, but he did with the mill. He restored it and, to a certain extent, built it with his own hands. Our two children were born when we were living at the Mill and all four children did most of their growing up there, so there was a huge attachment to it. I certainly couldn’t make up my mind whether or not to keep the mill and I was too much of a wimp to do so. I just said to Peter, ‘One is your inheritance, the other is your creation; you can make the decision.’

“Peter had a love-hate relationship with the house because when he was at Cambridge he didn’t have the freedom that our children had at their universities. Obviously the builders didn’t do everything so he always had a slight feeling that he ought to be over here helping Lucy with all that was going on: making the garden and fixing things in the house. Also, whereas the mill was a house of light, this is a very dark house.

“I remember somebody saying to him one day, ‘What are you going to do about having two houses?’ and he said, ‘When I start to think about it, I hold it here,’ and as he said that he put out his hand as if to push it away. He said ‘One day something will happen which will make me make a decision.

“We still had the mill when he was out walking our dog in 1999, and between one step and the next, he died. So I had to make up my mind and it was the hardest decision I have ever made. It was really difficult, but I’d spent nine years building this up. I don’t think it was attachment. I just felt that if I gave this up I’d wasted nine years of us living all over the place and not having a sensible – normal by other people’s standards – life. So I thought that would be a bit of a waste. Anyway, you can see what decision I made!” TF

Lucy wrote her books sitting at the table in this room. The inglenook discovered by Peter is in the background

Part 2 of Diana’s interview can be found here: Part 2

Interested in children’s books? See our interview with Graham Oakley here: Graham Oakley