Have you ever had a product you loved, which worked brilliantly and did almost everything so well that you were prepared to overlook its minor flaws? Of course you have! And when it eventually wore out and you tried to buy a replacement, did you find that it had been discontinued and superseded by something which boasted lots of improvements, but was not necessarily what you were after? Read on…

80-year-old gramophone technology still going strong

One thing which always amazes this Polymath writer is how processes and products advertised as being totally new and innovative usually turn out to be nothing more than replacements for processes and products which were already functioning to everyone’s satisfaction. Marketing departments and news headline writers are very good at making it seem as if the latest development has appeared out of the blue, created by the mind of a lone genius.

New products and technologies also tend to be marketed as being faster and more efficient than anything that has existed before, which sounds great, but quite often those benefits act as a smoke screen for what’s really driving the changes. What really makes the difference is whether or not money can be made from the effort. If the new product or technology cuts costs in terms of manufacturing, materials, transport and so on, then margins can be increased and sales prices reduced, and there is nothing more appealing to people than lower prices.

Of course, in order to reduce sale prices and up manufacturing profits something has to give and that is usually build quality. Modern consumables are designed to have a short life, based on the understanding that they will be quickly superseded by a new development and the buyer will replace them. The result of this dynamic is that as products and services become faster and more complex, their quality often gets worse.

It is also the case that many design improvements never amount to anything at all, even if they do offer superior speed and efficiency, because there is no financial incentive for anyone to turn the improvement ideas into a reality. When that situation arises, the existing slow and inefficient product or technology is likely to remain in use, unchallenged, until a profitable alternative eventually comes along.

Ways and Means

Progress, in truth, is much slower than headline writers and advertising people make it out to be. Things actually tend to inch along, albeit with the occasional breakthrough, and the process is messy and non-linear. Often there are numerous competing inventions being developed at the same time, overlapping in some areas and uniquely good and bad in others. Great ideas come to nothing, poor ideas succeed through clever marketing, and nothing is as clear cut as it seems.

Take the wonders of email, for example. Before most of us started using email, in the mid to late 1990s, sending an image or document was mostly done by posting or delivering it by hand. When email came along, however, suddenly it became possible to grab a file, attach it to an email and send it anywhere in the world. Magic!

Of course, it wasn’t quite that simple. Without a scanner, getting the image into the computer was sometimes tricky, and then there was the small matter of formatting. It took a while before the JPG file format became standard, and until broadband superseded dial-up connections, everything had to be crunched down into a Zip or Stuffit file so that it was actually small enough to send without bringing the whole system grinding to a frustrating halt. What’s more, the first email as we know it was sent at the start of the 1970s, so just getting to the home dial-up stage had actually been a long time coming.

Nevertheless, although there were problems which took a while to overcome, email eventually made it possible for images and all sorts of data to be ported about the communication networks by ordinary people with access to nothing more than a basic home computer and related equipment.

Nowadays it is hard for some of us to make it through a day without using email and the Internet in some way, but a couple of decades ago everyone got on just fine without it. The reason for this is that there were good, solid systems in place which offered more or less the same service at the expense of a little more effort. And, of course, no one bemoaned the extra effort, for that was the norm. Email was, in fact, more of a development than a revolution.

In May 6th 1937, the German airship, LZ 129 Hindenburg, having crossed the Atlantic and arrived at Lakehurst in New Jersey, famously caught fire and plunged to the ground in dramatic fashion. The whole disaster was caught on film by the many photographers on the ground. They may not have had digital cameras and internet-enabled devices for sending their snaps all around the world, but after the film was developed the images were scanned and distributed using a service called Wirephoto, developed by the Associated Press organization in 1935, which made it possible to wire a photograph to a newspaper on the same day it was taken.

The image was scanned using a type of fax machine, and the resulting signal was then sent through the transatlantic cable networks which had been laid on the sea bed many, many decades before. The equivalent machine at the other end of the line turned the signals back into an image by inversing the scanning process, and the resulting picture was then ready to make print news in the relevant country or district. The whole process required large and relatively expensive equipment, a fair amount of labour and was certainly not as fast as sending an image via broadband, but the systems built around the service were finely tuned and efficient. Portable darkrooms were used to develop the picture plates on the spot, after which they were ready to be wired immediately using portable transmitter machines connecting to standard phone lines. It was not really possible for any of us to affordably do much better from our homes until 60 years later, and even by 1937, the fax machine had been almost a century in development.

Bakelite telephone. The old dials were slow but speed isn’t everything

Other Systems

Of course, although many businesses and public offices had telegraph and fax machines by the middle of the 20th century, most individuals had nothing of the sort, so for them there were other systems of communication which functioned almost as well, albeit on a local level.

Before telephones made their way into every household, the post was the main means of proxy communication, and it was possible for a Londoner to converse with another Londoner over the course of a day using the postal service. In Victorian times, for example, there were as many as twelve mail deliveries per day and by 1927, the capital had its own Post Office underground railway for moving mail between sorting offices. Logistics prevented the same frequency of communication between places further up and down the country, but the national mailing system was still impressively fast and efficient thanks largely to the mammoth rail network.

Even when a well-heeled Victorian decided to head off on a tour of the world, the distance didn’t prevent them corresponding daily with their loved ones back home. Granted, there was a time delay, but constant communication between any two places was easily possible through the intricate and efficient systems which had been established.

Looking further back in time reveals numerous similar examples of efficient systems achieving impressive results, even by modern standards. The Roman coliseum, for instance, was built in just eight years, which is not much longer than a build of that size would take today. Of course, the Roman’s used slave labour to get it done, but they lacked trains, trucks and cargo ships for moving materials, machinery for mining and cutting raw materials, computer engineering packages for designing the structures, telecommunications systems for coordination, not to mention the cranes, drills, mixers and steel scaffolding essential to the construction process. What’s more, although the Coliseum’s marble finishing is long gone, much of the stadium structure is still standing, 2000 years on. Pretty much the same can be said about the Egyptian pyramids, which are another couple of thousand years older still.

These examples show that although industry has become more efficient in terms of labour and cost, its results are actually not massively different from those achieved by civilizations and societies of the past. And as for quality, it is doubtful that they are designed to last anywhere near as long.

The Colosseum in Rome. Still very much standing after a thousand years or two

Ever Diminishing Returns

Looking back, it seems amazing that people could achieve what they did with the equipment and technology they had at their disposal, given that we can hardly do much better now with the benefit of countless supposedly life-changing technological advancements. But they managed it because of a particular human trait, which is this:

The less someone has, the harder they tend to work to get the most from it.

And people really used to work extremely hard to get the most from their technology and equipment. Conversely, as products and services become more and more advanced, the people that use them make progressively less use of each feature, partly due to a lack of time and necessity. This pattern continues until, in the example of a continuously-developing product, it ends up with so many features that only a tiny fraction of its potential capability ever gets used by anyone. Thus the designed process starts being driven by marketing rather than by a genuine need for it to function a particular way.

We’ll discuss the way marketing drives the design process a little later on, but first it is important to give an example of how increasing sophistication results in underuse.

When I started becoming interested in recording my own music, my bandmate and I pooled our money to get a keyboard which offered something like 128 preset sounds. This seemed like a lot to us at first, but when we saw that the sounds were divided into basses, drums, organs, pianos, brass, effects, strings, and so on, we found that there were actually only a few options in each category. Nevertheless, the sounds were made up of layers which could be muted and changed for other layers and, importantly, all the parameters of each layer were editable. Not that the sober row of black buttons and tiny display made the keyboard’s editing potential obvious, but eventually, after studying the manuals in great depth, we milked that keyboard for everything it was worth!

Because we had very little else at our disposal, we were forced to learn the ins and outs of our gear, which pushed us to do greater things with it than we would if it had come easily.

10 years later, the war between manufactures to provide more and more saleable features resulted in keyboards and sound modules promising thousands of sounds, organised into endless memory banks. Storage memory had become cheap by this time and there was an abundance of independent sound designers offering sound collections. In this environment, each new product outdid its competitors by offering more sounds, effects and features than the last, to the point where it took days just to audition the basic presets, let alone try them out in various songs or carefully edit their parameters. Furthermore, it could all be bought for less money than it had cost to get a keyboard with just 128 sounds and no effects, 10 years earlier.

The result was that, rather than eek the very last morsel of goodness out of a keyboard by learning to program and edit its parameters, users had the option of flicking through the hundreds ready-made sounds until they found something they liked. The carefully designed programming options went unused and, if anyone did eventually get bored of the presets and expansion soundcard options, before they had time to start looking into just what else their keyboard was capable of doing, something new came out with even more sounds, effects and processors.

At one stage, everything I bought seemed to come with CD-ROMs full of samples which, quite frankly, I never even had time to listen to. Sounds were 10 a penny, and had quite literally become devalued.

Why, for example, in the 1964 Bond film, Goldfinger, did Auric Goldfinger want to contaminate Fort Knox instead of simply stealing the gold inside? It was because by making the world’s largest reserve unusable, his personal gold reserves would become more precious and valuable.

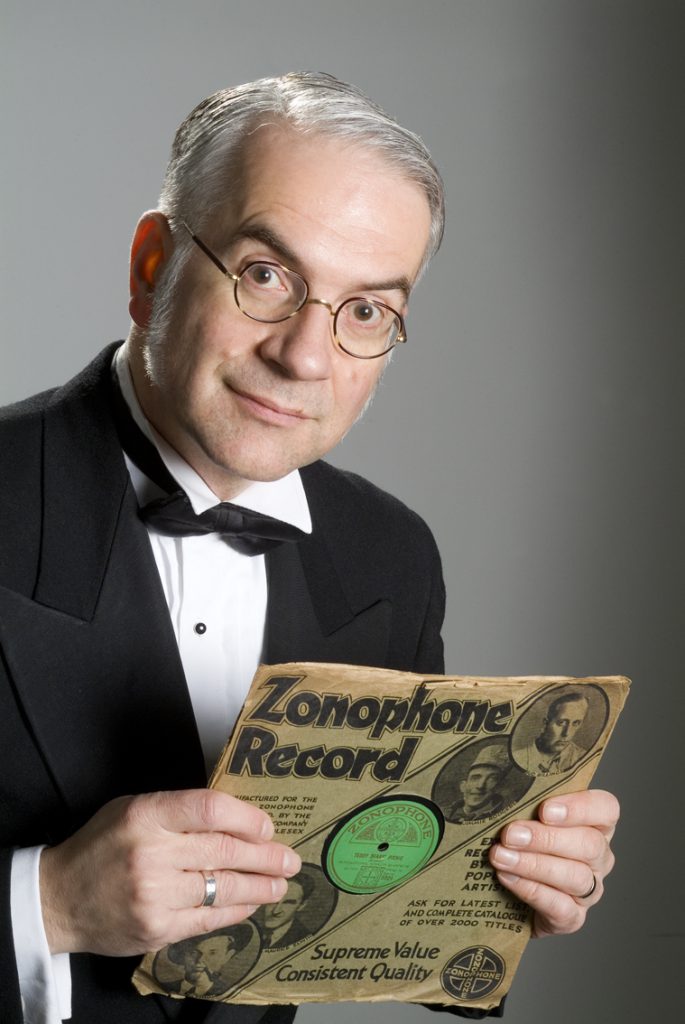

DJ78 (Dave Guttridge): “Nowadays people have no connection with the music they are listening to at all and, as a consequence, it has been devalued.”

Giving It Away

Interestingly, the same kind of devaluation process can be seen happening with music itself. In Issue 3 of Polymath Perspective, Dave Guttridge says, “Nowadays people have no connection with the music they are listening to at all and, as a consequence, it has been devalued.” Dave is far from the only person I have met who has expressed this sentiment; most people who earn their living from producing music in some way say roughly the same thing.

Recently I saw a brief clip of a young man being interviewed who was bragging that he had 8000 MP3s on his player. In terms of albums, that equates to roughly 600 plus LPs, and should have cost him something like £4000. The likelihood seemed to be that, unless he was especially rich, he had downloaded most of it for nothing. This being the likely scenario, a few questions came to mind.

Firstly, had he listened to each song? If each one was four minutes long, for example, that would equate to 533 hours listening, or 22.2 days if listening non-stop, without pauses between tracks, 24 hours a day, playing each song only once. My guess is that he had not listened to the 8000 tracks and probably had no idea of who had written, recorded, engineered, produced, played, published or released the vast majority of the material. I also suspected that he had no concept of when any of it was done, or in what social, political or historical contexts. Had he ever seen any original artwork? Had he heard any of the tracks in the album context in which they had originally been conceived? Did he even think about how that product came into being?

Did he consider that gear manufacturers, record retailers, distributors, warehouse workers, studio technicians, managers, musicians, roadies, producers, and many other highly-skilled people, all relied on the income generated from the sale of that end product for their continued employment? I think not. To him all amounted to just one thing: the impressively large number 8000.

Unfortunately, copying MP3s is something many people justify in their own minds. There are all sorts of very poor arguments used, which usually suggest that record companies have been ripping people off for years and are now simply getting what they deserve. Even if there is a grain of truth that generalisation, copying MP3s is still an infringement of the copyright of the artists and labels and is theft, plain and simple. What’s more, it is a mean insult to the people who have worked hard, and usually sacrificed a great deal, to produce the music in the first place. And the truth is that, for every Elton John, there are thousands of musicians and composers who make less than the average wage from their records, despite selling reasonably well.

Proof that the practice known as file sharing is wrong can be plainly seen when looking at what has happened over the last decade or so as a result. Record labels no longer make money and therefore cannot pay studios and so most of London’s top studios have closed.

As producer and studio owner Hugh Padgham says in our interview in Issue 3 of Polymath Perspective, “The problem studios face is that the people who run them have to pay extortionate rents and, ever since it became possible to record something in your bedroom, record companies haven’t wanted to pay for artists to come into proper studios. That is completely and utterly biting the hand that feeds them. I think they are pretty much the prime destroyer of studios so I don’t really work for labels any more; I have such antagonism towards them.”

What Hugh says may well be true, but it is also worth considering the problem labels face, which has caused them to squeeze studios. Those record companies who were supposedly ripping people off were also investing their profits in new acts, many of whom were very interesting, but didn’t necessarily make money. In the early days of Virgin, for example, the huge sales of Mike Oldfield’s records allowed the company to sign a large number of very interesting bands and artists who actually didn’t bring in any revenue. Nowadays those types of acts do not get signed. The labels can only afford to spend the huge sums necessarily to successfully promote a band on one or two of their acts. And this favours the safe bets – the mainstream acts.

Retailers had healthy margins on CD sales, of course, but they had high-street rent, staff, security and insurance costs to pay while maintaining enough cash flow to stock the shelves.

Even the quality of record production is under threat from the squeeze, which is forcing many of the world’s top producers and engineers to look for other work. Hugh Padgham explains part of the problem. “Producers used to make money from record royalties, but the sales of records are so depressed that you can’t any longer. It’s like a loss leader, and if the producer doesn’t have some ownership in the music copyright then they are not going to make a living. I am not going to spend six months making a record in the hope of getting a royalty later down the line, so I have a deal with the band and if it takes off then I’ll benefit and the studio will get paid.”

The final word on the matter must go to Marius de Vries, who we featured in Issue 2. He says emphatically, “The business of making records and distributing them, as it is has been understood up to now, is over – it’s finished! No one’s buying records so the whole infrastructure upon which the record industry is based has eroded or subsided.”

Marius de Vries: “The business of making records and distributing them, as it is has been understood up to now, is over.” Photo by TF

Making the Most of Value

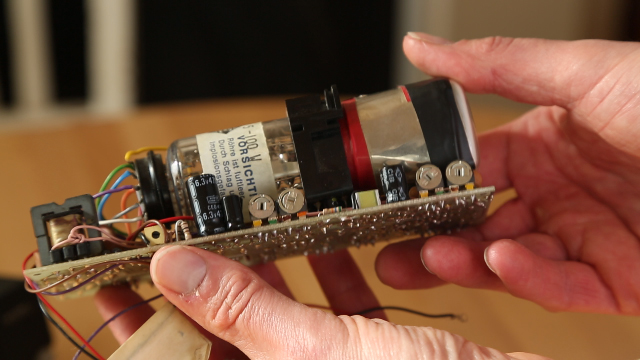

The idea that something has to be valued for its true worth is not only applicable to music, but also to objects and equipment. A number of Polymath Perspective’s interviewees have expressed their appreciation of equipment which might be considered outdated and worthless by a society driven by consumerism. None more so, perhaps, than interviewee Dave Guttridge, who DJs with 78 shellac records using gramophone players designed 80 years ago.

At one point in his interview Dave says of his gramophones “Underneath they are beautiful pieces of equipment with absolutely stunning engineering, and they made millions of the things. And HMV never changed the design. They made the 102 model gramophone from about 1931 right through to the late 1950s without a single change to its design.”

What we find out from Dave is that gramophones, like the wax cylinder, became obsolete, not because they worked badly or wore out, but because more convenient formats arrived, which enabled manufacturers and record labels to use a little marketing hype to sell the same thing all over again… and again!

Another interviewee, Rick Dickinson, featured in Issue 2, explained how the need to sell something new is often the driving force in design, rather than a genuine need for improvement. Rick says, “…very often there is a lot of distracting activity like specmanship, by which I mean aiming to have the most impressive spec. They will want their product to have more knobs or buttons, a little bit more power, or a slightly bigger and brighter display than the competition, but I ask ‘Why? Does that relate to the functionality? Does your ergonomic study say you need another button? What is that extra button for?’

“They might answer ‘Well, the competition have got 10 buttons so we want 11.’ You might think that is laughable but that is very often how it is. It’s quite a sad world in some ways. People are forever trying to out do one another and it’s not about product design. It’s about other things, floated under the heading of the product being better than the last. It’s driven by people wanting to make a quick buck for the least amount of effort.”

Rick then goes on to say how the result of supposed product improvements is not always a benefit to the consumer:

“Often you find it is not better and you actually preferred the way a particular function of the last generation product worked and wish they’d retained it. It’s a bit like when you update your computer software. They’ll have improved some thing but spoilt something that was right. You get it in automotive design as well. Next year’s model of the same car: it’s different, not better.”

What seems to be coming across from these quotes by our interviewees is that a lot of fantastically-engineered and useful products are forced into redundancy when there is nothing much fundamentally wrong with them. That being the case it is prudent not to dismiss something because a sales team is denigrating it to help promote the benefits of a newer product, as it may still have its uses.

Veteran illustrator, Graham Oakley, who created The Church Mice series of books, and was interviewed in Issue 1, has a traditional style of illustration, but he takes a very pragmatic approach to what’s new. At one point, he explains how he now makes use of photocopying to aid his work, allowing him to work over the dummy versions of his books so that he can bypass having to re-do the roughs.

“These days I work on top of the dummy, so I don’t really do roughs any more,” he explains. “What I sometimes do, if I feel a thing is not going well and starts looking a bit overworked, is make a computer print of it and then paint over the computer print, rather than do the whole thing again. I just don’t have the patience for that anymore.”

Graham is, quite understandably, using technology to save time and effort rather than because it gives him better results. Of course, his results are good enough already.

When we spoke to film producer and director, Richard Bracewell in issue 2, he revealed that for his low-budget film The Gigolos, he used traditional 16mm film, rather than cheap and convenient modern digital technology, because the quality of film is good. To make this possible and affordable at the same time, given the high-percentage of night-time filming he was doing, Richard bought discounted night-time film stock and adapted it using light filters when shooting in natural daylight.

“If you haven’t got enough light you can’t shoot with either film or digital,” explains Richard. “You can’t make light out of nothing. But it also depends on speed of the film and whether you are shooting on 16 or 35mm. We shot everything on the same stock of 500T which is tungsten and very, very fast. When we were shooting in daylight it was colour corrected by placing filters in front of the lens, rather than sorting it out in the grade later on. So we did as much as possible on location.”

Both Richard and Graham adapted the resources they had at their disposal to get the most from them and this is something other Polymath interviewees have talked about too. Dave Guttridge, again, spoke about how his forward-thinking father adapted his reel-to-reel and record deck to explore ways of editing and synchronising music.

Then in Issue 1, Brian Eno says “When new media appears, like the iPod, it is for historical reasons. For example, people wanted to carry all their records around and that’s how this technology started. We used to carry a walkman and cassettes so this was invented as a more elegant solution, but, of course, what is always interesting about new technologies is that as soon as they exist, you find that they can do something that nobody ever thought of before. The historical reason for things existing is never the most interesting thing they can do.”

And in Issue 3, Diana Boston explains how her husband, Peter, made use of the photography process to invert his early illustrations to achieve an unusual affect, and Brian Flint describes how he used arcane programming languages and methods to empower his electronic designs.

The ‘ISIS’, a GSM/GPRS enabled gaming, comms and GPS device concept by Rick Dickinson

Relative Values

After my interview with Rick Dickinson earlier in the year, I found myself explaining to a friend my thoughts on what Rick had said. I was specifically using a mobile phone as an example of something which is a technological miracle, in many ways, but is totally underused and unappreciated by the majority of its users. As Rick put it: “I should say that 99 percent of the people who use the iPod, or whatever fashionable high street, high-volume product it is, have no notion whatsoever of the monumental risk, foresight and investment that has gone into getting that product into their mitts.”

I explained to the chap I was speaking to, that I thought a modern phone was, relative to something from the 1960s, immensely powerful in terms of technology, and how this was ironic because the vast majority of people used it like a flashy toy, sending endless snappy photos and inane, unnecessary texts and had, as Rick put it, no notion whatsoever of the monumental risk, foresight and investment that has gone into getting that product into their mitts.

As a whole, the new features and apps which are used to market new phones have a similar combined kudos as the ‘8000 MP3s’ ripped by the aforementioned youth speaking on television. In other words, they actually have no individual value because their abundance has had a devaluing effect. I explained that I thought that no one actually sits down and thinks hard about what they could potentially do with the features of this powerful and incredible piece of design engineering. They literally cannot grasp the value of what they have.

The chap replied, “I don’t really see what you could do with one,” and that was the end of that! I just thought, “Well, I’d love to be able to travel back to the 1940s and hand one of these devices to the Bell Laboratories staff and see what ideas they would come up with for its uses.’ Surely they would be more inspired than we are today.

So, what is the conclusion of all of this? It is simply that we should try to identify the true value of things, for it is a hollow goal to chase after the new and novel thinking that it will make everything much better. Necessity is said to be the mother or invention. Perhaps, in that case, luxury is the father of complacency and under-appreciation. TF