The View

The Sunday was windy and the sea rose up, grasping at the furthest parts of the beach before sliding back again. With a crash, it tried again, breaking into white fingers and then slipping away once more. The air became misty with ocean droplets suspended by the wind. Screams could be heard from the edge as children thrilled themselves with games of ‘chicken’. Somewhere over the furthest purple blue was the African continent. A very different place, and a harder sun.

The stone house, Ella’s house, stood detached, overlooking the bay. It had a certain distinct style and could be found, rendered in glorious peachy red, on several picture postcards. Almost no one ever wondered about this place or its owner when they looked at the image. It was famous but anonymous – seen but not seen.

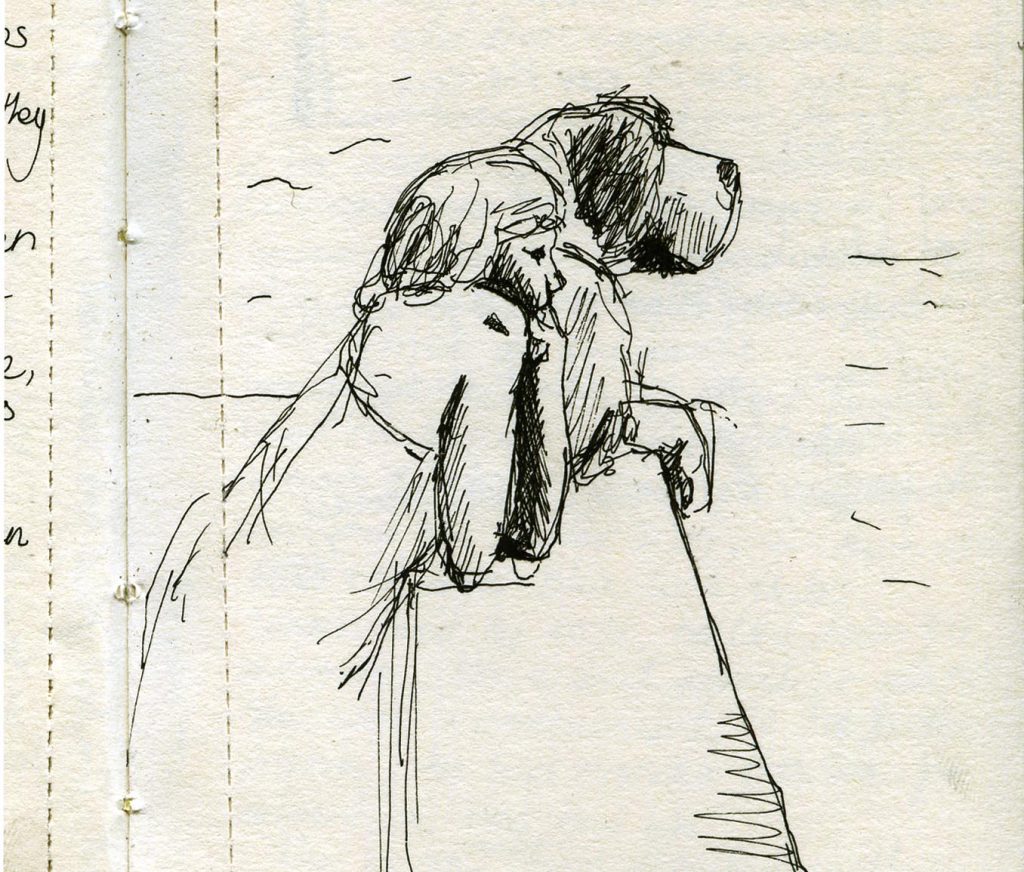

Every day, Ella appeared on her rooftop balcony, studying her view in passive fashion. If anyone cared to glance up they would notice her there – leaning on her elbows, supporting her chin in her hands – but few people ever really looked up. Ella was static; a monument to her friends, who had long since crossed the sea in search of adventure and a new life. She stood, not waiting, nor wanting to go. Whether she was resigned to her fate or satisfied with her days, it was hard to tell. Below the balcony, the sea gasped, laughed, mocked and hissed relentlessly, but it no longer caught her imagination.

Ella had inherited half of the house from her parents some forty years before. The rest belonged to her absent brother, a keen photographer who, after some initial commercial success, found himself lured away by the prospect of exploring foreign lands and capturing other exotic views on film. Perhaps fame was waiting for him over the horizon. He had to find out. Ella had neither seen him nor received word from him since his departure in 1968.

There was only one road to the beach. It came from the East, snaking its way through the craggy inland mountains, before finding the coast and hugging its contours. On its journey it passed many hotels and restaurants which were full of life in the summer months but desolate when the tourists drifted homeward.

As the road neared the sea front and the land flattened out, a passenger could gain their first, brief, glimpse of the peach-coloured house on the left, if they weren’t too busy looking out for sand and surf. From the road Ella’s home was partially concealed by a hedge of fir trees, but anyone standing by the shore, or appreciating the vista from one of the cliffs that surrounded the bay, would have it in their sights.

The builder had angled the house so that it turned slightly away from the road; its windows and balcony overlooking the cove. The view was of a shell-shaped area of shallow, clear sea, which arrived at the shoreline by passing through a narrow channel, bordered on each side by steep, rocky, tree-covered hills. Beyond it all was the open sea, stretching to the horizon.

At one time the craggy hills were joined in the middle, forming a continuous band of rock across the channel. Relentless as it is, the sea had eventually cut through where if found a point of weakness, eating out the shallow, secluded, bay behind, and depositing a golden carpet of sand. The remainder of the hard rock crags became gateposts, standing guard on the open sea, sheltering the bay and its villagers from storms.

But for Ella, the geological history of the bay had no significance. She did not think of it as something that had been made. In her eyes, it was simply a view.

During the summer months people flocked to the small sandy beach, and coaches full of culture-hungry tourists crawled up the winding road to visit the old monastery that had been built atop one of the surviving outposts of rock. The original monks had evidently chosen the site because it was rather hard to reach, however, this meant that now buses and cars queued all day long at the seafront, patiently waiting their turn to amble to the top amid clouds of hot diesel exhaust. Strangely, the modern monks didn’t seem to mind being part of the local tourist trade. Perhaps, after all, they enjoyed the company.

It was from this very hill that the bay had been photographed for the local postcard. The panoramic image showed the bay at its best, in glorious Technicolor, but dated back to the late 1960s. In the picture the cars were dwarfed by the landscape – just tiny blobs of pigment – but their telltale vintage designs were still evident enough to give the game away. Nevertheless, no one had seen fit to update the picture. After all, the hotels and their awnings were only subtly different and no one cared that the fir trees outside the peachy house looked a little less mature in the picture than they appeared during the holiday. For sure, the tiny sun-drenched youngsters dotted about the beach had reached middle-age long ago, but they had been replaced time and time again by newer sets of brown, bikini-clad bodies, continuing the tradition of sun worship.

Ella, although not visible in the image, peered out over the bay on the same day that the postcard photograph was taken. Perhaps she was inside at the time the shutter flicked open, asleep and dreaming of the experiences and adventures her life might bring. It was the week after that that Ella’s brother, camera in hand, took a boat heading south west to the Americas.

On the Sunday it was windy and Ella stayed inside. After all, even if she didn’t feel like going out, there was always tomorrow. TF