In part 1 we heard how Lindsey entered a competition with the specific aim of explaining how her upbringing in a separatist religious cult, and subsequent exclusion from it, drove her to seek security and acceptance from society through her body image. In Part 2, we find out if the publisher shared her vision.

Your vision is different to ours…

Following the return of the ghost writer to Paris I waited impatiently for correspondence from him. Tom kept reminding me that, by his calculations, transcribing four days of interviews would take at least two weeks, so I trusted the ghost writer was getting stuck in, familiarising himself with the text, my modes of speech, thought processes and so on.

Much to my disappointment he hadn’t taken the opportunity to look at my box of photos during his stay in England so, undaunted, Tom set about scanning a selection of photographs of my family which I emailed on. I wanted the ghost writer to have as much information as possible so he was able to create an accurate portrayal of my life. I’m not sure he saw it quite like that, though. As he said in one email, “I’m the one with the easy job. I just have to organise it so you can be proud of it and so readers will get the picture. That’s how I see it: trying to make pictures from what you told me. Like paint-by-numbers. The numbers and the picture are yours. I just have to help you connect the dots.”

It turns out what he meant by ‘organising it’ was cutting and pasting the text that had been transcribed by a third party – a practice which is, according to the publisher, normal. Tom was appalled. As an experienced interviewer, his view was that transcribing is vital when trying to produce accurate and coherent work, for it is a fundamental part of the writing and editing process.

I felt I had been seriously misled by the ghost writer as I’d said to him at least once that I didn’t envy him the task of transcribing the mountain of words I had spoken, yet he never let on that the job was being carried out by someone else. Clearly the ‘strictly confidential’ warning only applied to me!

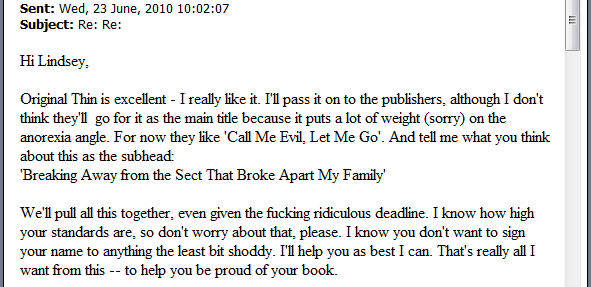

I knew that the ghost writer was extremely worried about the tight deadline because he’d said so several times, referring to it as being ‘impossible’. I found it unbelievable, therefore, that on his return to France, instead of working his socks off on the project he had gone back to his day job at the magazine. I couldn’t believe the publisher would hire someone to write a book in no time at all when they had other work commitments and no relevant experience.

The ghost writer suggested I watch Son of Rambow – a film about a young boy who belonged to the Plymouth Brethren – to ‘see how it compared to my childhood.’ I’m sorry to say I did so willingly. The film bore almost no resemblance to my experiences and I told the ghost writer this. During a phone conversation I had with him he told me that he had been reading several books about the Brethren and other religious sects. I found it extremely odd that he was concentrating his energies on watching a film and reading books that were irrelevant to my experiences. I had spoken to this man for four days, and he had more than enough material to work from. If that wasn’t enough, why not research the Exclusive Brethren, who separate themselves off from the other Brethren? What about looking into eating disorders and mental illness? And how about researching what life was like in a British town and school in the 1980s? I trusted that he and the publisher knew what they were doing.

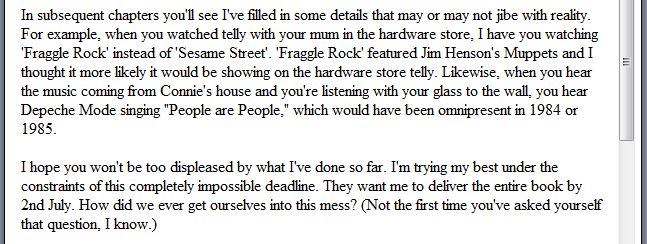

This trust extended so far that I found myself reluctantly agreeing with the ghost writer that details I couldn’t remember, such as the music I’d heard played by my neighbours, or television programmes I’d secretly seen at a friend’s house as a child, could be made up by him. At the time Tom expressed his disapproval. To his mind fabricating any detail, however minor it may have seemed, was wrong.

“If you can’t remember,” he said to me, “then just write that you can’t remember.”

I, however, was convinced the publisher and ghost writer knew best and dismissed his concerns.

Jibing with reality: Depeche Mode, what else could it have been?

First to Arrive

The first text from the ghost writer arrived in my in-box on 22nd June. There were 3077 words in total, yet the target was to produce a book roughly 80 000 words long by 2nd of July. To say I panicked at this point is a major understatement, but that was nothing compared to the disbelief and anger I felt as I read the text. Let me put it this way, if he had spent as much time on the quality of the actual content as he had the atrocious title (Pray For Me When I’m Gone), and a half page introduction to the book called the Author’s Note, I might not have reached the heights of outrage that I did.

Like a ton of bricks it hit me that not only was I up against an impossible deadline, but what little text there was read like a series of sensational tabloid headlines, barely connected to one another and nauseatingly sentimental. The style of writing was childish and nothing like the sophisticated psychoanalysis I had dreamed of.

He had at least looked some of the photographs I‘d sent him, but instead of studying them to familiarise himself with my family, he had quite literally described one photo.

“Dad is wearing sandals, white trousers, a blue sport shirt, a beige wind-cheater, and he looks like a tall Phil Collins. Mum is wearing thick brown shoes, a calf-length floral-print skirt, white tights, white headscarf, and she looks like The Lady with the Lamp.”

I was already deeply doubtful about the morals of exposing my parents and friends in a book, and felt that I could only go on if it was to be fair and honest. Faced with text that was full of exaggerations and untruths, I suddenly realised Tom had been right: by permitting lies to be part of the text, I was making a mockery of the truth of my story. The prize, rather than being rewarding and enjoyable, was turning into a nightmare.I turned to Tom in despair.

“My name is going to be on this,” I said, looking him in horror. “I can’t do this. I’m pulling out now.”

I didn’t. Tom persuaded me to stick with it, saying that we should talk it through with the publisher as she had said to call if we needed anything at all.

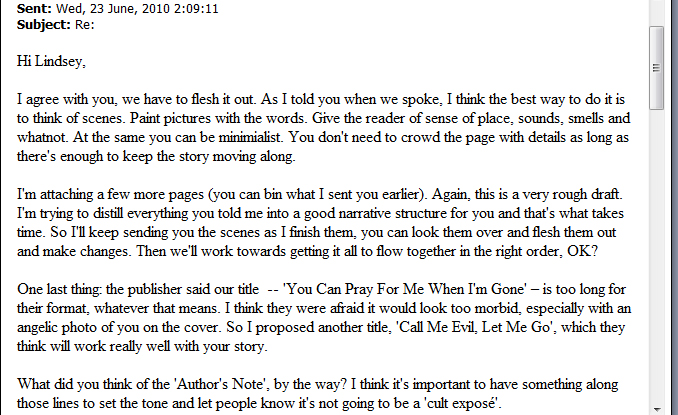

The next day I rang the publisher hoping to have my mind put at rest. I was certain she would appreciate my anxieties and might even assign a new ghost writer to the job. Instead she tried to appease me, calling the work ‘very strong’, and I was left feeling she hadn’t understood my worries at all. So Tom called her and spoke to her for over an hour, re-addressing my concerns.

He quoted the Phil Collins text as an example of the many problems I felt there wasand suggested that I should be allowed more freedom to write, as he thought I could write well enough to tackle book segments rather than work as a slave to the format Ihad been given. Tom also asked if I could see the transcripts, butshe nipped any such ideas in the bud, stating that there was no time for me to write the book myselfand insisted that I work to the structure laid out by the ghost writer.

She told him that normally they would have six months or more to work on a book, but as the deadline was so short I was not going to get the book I wanted. She insisted that I could write that in the future!

Tom did manage to get the publisher to understand that by having only a little text it was hard for me to judge how the book was going to progress. She agreed to get the ghost writer to send a sample of what he had written for the anorexia part, which she promised would be more analytical, and also provide me with his plan for the book so that I could get an idea of what was to come.

After the call, Tom’s advice to me was to go ahead with the book, spend the prize money on a nice holiday, but ultimately forget it was anything to do with me,which it wasn’t going to be, judging by the text I had received from the ghost writer thus far.

Ghost writer’s advice: paint a picture with words…

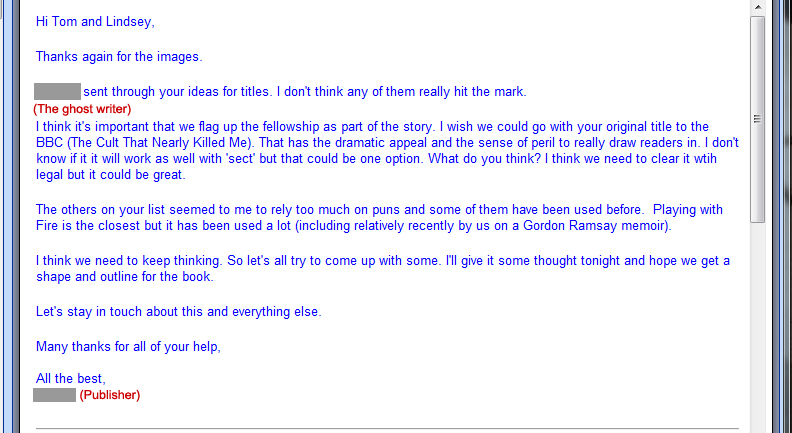

Breaking Away From the Sect That Broke My Family Apart – so that’s not too long then?

The Misery of Memoirs

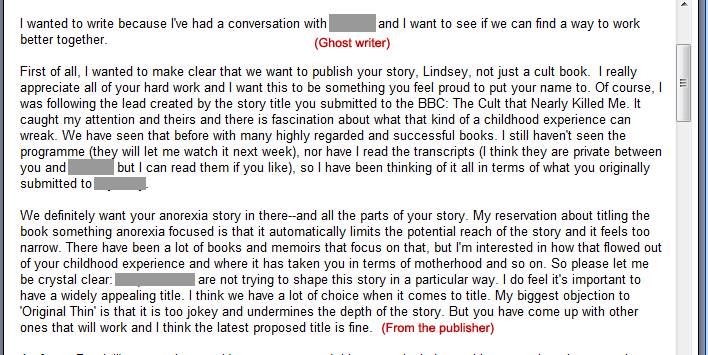

It was very disappointing that the book I wanted to write appeared not to be the book the publisher wanted to sell. I did a little digging and discovered that my publisher specialised in producing a genre of autobiography called the ‘misery memoir’. The misery in question is usually that of a person suffering terrible abuse or trauma during their childhood, and the horrific experience is told in graphic detail to gain the unconditional empathy of the reader. By end of the book the protagonist has to have triumphed over adversity so that there is a happy ending and the reader can go away feeling inspired. Unsurprisingly really, there have been a number of literary hoaxes over the years and the falsifying of events to supplement true experiences is not an uncommon occurrence.

With increasing horror and disgust I realised the fate of my book. Nonetheless, I ploughed on, suggesting that the ghost writer send over the entire text so that I could just get on with the dispiriting task of filling in the detail he wanted. Given that what I had been sent lacked any detail, I could see that it was up to me to do a huge amount of fleshing out, and somehow fit that in around my work and the needs of my children.

A couple of days passed but no more text arrived. I wrote a few hundred words of my own, writing honestly events that the ghost writer had hideously distorted. Words flowed and I felt really pleased with both the style and the content. I felt I had engaged with the simple, direct style the publisher was enforcing, whilst still retaining my integrity. I tentatively let Tom read it though. He suggested a couple of changes but otherwise thought it was great, and had no doubts that the publisher would too. For us, the most important thing was that the text sounded like me. Tom was pleased that it better reflected my humour and view of the world than the work the ghost writer, while I felt it more accurately portrayed me as the mischievous and cheeky child I really was, rather than the two-dimensional innocent they favoured.

The ensuing comment from the publisher that the writing was ‘flat’ hurt me and baffled Tom. The ghost writer’s reply was patronising to say the least:

“I think it’s important in these early chapters (maybe in all the chapters) to avoid the tendency to analyse. Let’s paint a picture of what happened in your childhood. If the picture’s good and clear, the meaning will come through all by itself.”

I wanted to scream, and probably did – many times. It was increasingly clear that, rather than simply tell my story as it happened, my anecdotes were being used to flesh out a misery memoir about a fictional abusive cult (renamed the Fellowship by the ghost writer for legal reasons). And, even more than that, he and the publisher were prepared to tell me one thing with the clear intent of doing another, for whatever commercial reasons they had discussed in private.

One issue was that of ‘the voice’ that the book was going to be written in. At every opportunity I was told that the voice should be an innocent child-like one to reflect my early years, and this was given as the reason why the early text was so simply written. Tom and I discussed it and concluded that they might have a point in that a child would not self-analyse, even though that is very much the way I think about things today. Strangely, though, the early text from the ghost writer contained adult concepts. At one point, for example, it described love as a metaphor. Elsewhere it presents a paradox – not really the voice of a child. Their reasoning did not make sense and we were confused by it.

As for the sample text I requested, which was supposed to show me what the more grown-up, self-analysing anorexic period was going to be like, it never arrived from the ghost writer. Furthermore, the emails I was receiving were gently suggesting that, actually, it wouldn’t be so bad if the style carried on more or less in the innocent voice all the way through. There was also no sign of the ghost writer’s plan that I’drequested, leaving us to wonder exactly what sort of book it was going to be.

No puns!

Plan B

Days passed, but no more text arrived from the ghost writer. I was ready to pull out again. I turned to Tom who, wanting to salvage the situation, proposed we draw up our own plan of the book,given that I still hadn’t had one from the ghost writer. That evening, once the children were asleep we worked together throwing ideas around until we hit upon a plan that we both agreed was truthful and engaging. By 2am we had completed the rough notes, and I set about typing them up first thing in the morning while Tom took care of the children. I emailed the plan to both the publisher, who acknowledged my idea, and the ghost writer. I heard nothing from the ghost writer until days later when he simply sent an email titled ‘Those damn Germans’. I guessed he was referring to the football result, but there was no mention of the plan I’d sent, or any other text for that matter. After much speculation Tom and I decided it must be a deliberate message to indicate that he was not going to respond to my proposed plan. My question as to whether there was supposed to be any text in the email was met with, well, silence!

Again I rang the publisher. She wasn’t available but rang back later and spoke to Tom. This time she described the ghost writer’s work as ‘incredibly strong’. She asked Tom’s thoughts about the work, perhaps mistaking his calm diplomacy as an indication that he, as a fellow writer, appreciated the qualities of the ghost writer’s direct style. His reply voiced his reluctance to get involved but, on being pushed, admitted that he thought the writing poor and was really disappointed with it. No sooner were the words out his mouth, when the voice on the other end of the phone climbed several pitches, stating in no uncertain terms that with 20 years of experience in book publishing she knew better than he. She also said she thought thatthe winners of the competition would just be grateful for the prize money.

By that I can only suppose she meant that she thought the money would be enough to keep the winner happy while the ghost writer and publisher colluded to produce a product that would make them as much money as possible, however far from the truth it took them. She said that if she absolutely had to she would go with my text, even if it ‘only sold six copies’, but herreluctance was clear.

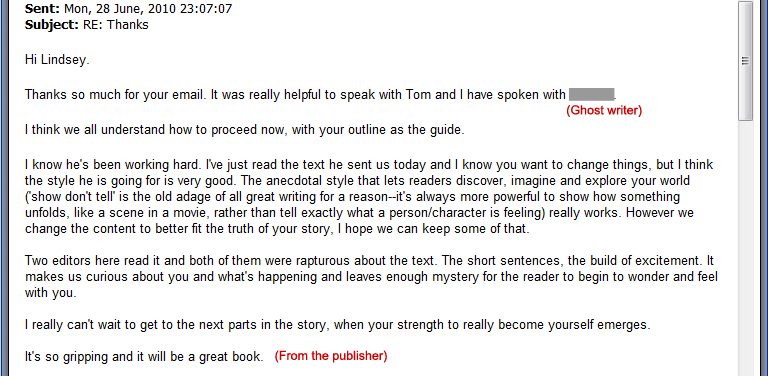

Despite her aggression and defensiveness she emailed to tell me that they were going to proceed with our outline as the guide. Hurrah! She was keen to point out, though, that we should still follow that old adage of all great writing which is ‘show, don’t tell’. Don’t worry, I hadn’t heard it either! Tom and I spent some time on Google investigating, and realised that my analytical style was exactly the sort of thing they didn’t want. Her email went on to say that the editors in office were now ‘rapturous’ about the ghost writer’s text. Apparently the ‘short sentences’ and the ‘build of excitement’ were perfect! I considered hiring a shepherd to trim the wool that they were trying to pull over my eyes.

I could hardly believe that we were daring to stand up to one of the biggest publishing houses in Britain, who seemed united in their stance. I was absolutely terrified but Tom, understanding how difficult I found it to challenge authority, remained outwardly calm and soothed my nerves.

Too jokey, let’s change you to suit the story…

Rapturous about the short sentences

Slow Progress

After that I finally received a reluctant acknowledgment of my plan from the ghost writer. The publisher must have insisted he replied, but the tone of his email was curt and patronising. He ended suggesting that if I didn’t like what he had been working on then he was happy to help me with my manuscript! Obviously I didn’t have a manuscript, whereas he had supposedly been working on the project for nearly a month. He knew I had nothing and so I took his comment to mean “You’ve got no choice but to work from mine.”

I sat down wearily to flesh out the text that I had been sent, which by this time amounted to 17,000 words, constantly trying to curtail my thoughts to make sure I was showing and not telling. To say the process was torturous is no exaggeration. Seeing the difficulty I was having with it, Tom dropped his own work to help me and wesat side-by-side in front of his computer working through awful paragraphs such as:

“When I was a little girl the Fellowship was what kept my family whole. It was like we were all stuck in a little pot of glue. Living, working, playing, praying, cemented together by a set of beliefs. Those beliefs bound us in turn to a very specific set of rules. Challenging those rules – any of those rules – was an affront to the Fellowship. Challenging the Fellowship was an affront to God.

As it turned out, the Fellowship wasn’t anything like glue.

It was the knife that ripped my family apart.”

The text was a mess of badly chosen metaphors clumsily put together. Every paragraph had problems, whether they were to do with information and feelings being fabricated, uncharacteristic quotes from the bible – I had told the ghost writer I didn’t read the bible – irritatingly trite statements about the Brethren, inconsistencies, crude over-dramatisations and poor writing.

References to ‘the fall’, ‘the block’ and other equally inappropriate Americanisms cropped up in the text again and again further highlighting just how far away the style was from what I might say in my voice. The overriding feeling was the book was in the voice of a stranger, not me.

Eventually we got through the fleshing out process, but it took us days, and we felt increasingly disheartened. We had colluded in producing something that was fundamentally wrong, fleshing out sections which had been doctored and in some cases, made up, for the purposes of the misery memoir format. Bizarrely, despite how poor we thought the text was, the publisher was sending ever more enthusiastic emails about what she was reading:

“This is so powerful and vivid. I am bowled over,” and, the other editors “are hugely impressed with your book. I think this is staggeringly good.” Whilst she assured us that the writing was incredibly strong, vivid and powerful, we continued to see it as incredibly poor, dull, disorganized, without structure, misjudged and incorrect. We were poles apart – this mass of editors who all apparently seemed to have free access to the text, and Tom and I, who, in contrast, were sworn to secrecy and isolated. The one thing it didn’t seem to be was my book.

Towards the end of that week I sent the publisher one more email to say that if I was to get through all the text I needed everything from the ghost writer as soon as possible. I was very concerned that I was expecting about 55,000 words to arrive during a week that I had school events to attend, not to mention my normal working week to negotiate. The publisher had vaguely referred to an extended deadline but would not say how much time I had. For all I knew, I might only be given a couple of days to work through the text. Experience told me that this wouldn’t be an easy task. I therefore requested that the text be sent through over the weekend to give me Friday, Saturday and Sunday to go over it.

This request was ignored by the ghost writer. I was growing used to his behaviour by then: ignore anything he didn’t like until it went away so he could carry on doing what he wanted. It was clear that I wasn’t going to receive any text at all from him that weekend. I just couldn’t see how a book was ever going to be produced in the time limit.

“Use what I’m giving you…” Yes Sir!

5th July, three days after the original deadline, and the text starts to arrive…

Last Resort

That was when Tom and I made a big decision: we would write the book ourselves. We decided that, for time’s sake, we would start with the text we had already worked through, line by line. On re-reading however, I found everything about it distasteful and unpalatable. Each time we reached a problem Tom would say, “I don’t get this, what happened here?” My reply became predictable: “Well, it didn’t really happen like that.”

Tom would say, “What do you mean, it didn’t happen like that?”

I’d reply, “He made that bit up. I didn’t think that and it didn’t happen.”

We had been drawn into colluding in the ghost writer’s fabrications, which was a crazy roundabout way of working, given that the truth was right there, in my head! Tom, who was at this stage sat at the keyboard, editing the paragraphs one by one in an effort to un-mix metaphors and remove American parlance, had had enough and said, “Look, there’s no time for this, just forget trying to fix it, it’s crazy, just tell me what happened in your own words and I’ll write it down.”

After hours of replacing the ghost writer’s inaccurate paragraphs, barely anything of his original text remained. And when there was nothing left of his to work on we continuedwriting. Working in parallel was clearly going to be the fastest way to proceed, so Tom tackled the latter part of my life from when he knew me, occasionally calling across the room with questions as to what happened in a particular situation, as I worked on my formative years. We already had our structure plan, it was just a matter of sticking to it and editing the sections together towards the end.

July 5th was the proposed second deadline, by which time we had completed 40,000 words. The ghost writer had sent over less than 2,000 more in that time. Come Monday morning, as soon as the children were at school and playschool, we sat down together – me at my laptop and Tom at his computer – and typed furiously. Every so often we stopped to make cups of tea and frantically discuss where we were and what bit to write next. As soon as the children were in bed we continued our work, not stopping until the early hours. This pattern continued through the week to Friday. We were exhausted but strangely delirious with adrenalin and didn’t notice. We had completed 75,000 words in five days! In the meantime I had received 28,000 more from the ghost writer, but it was too little too late and I didn’t stop to look at his work. We were too far into what we were doing and I was terrified that if I stopped to think about it I wouldn’t have the guts to carry on. With every email that dropped into my inbox my dread of a confrontation with the publisher grew.

Around this time I broke the promise of secrecy about the competition, confiding in Tom’s parents and a friend, asking them for help looking after the children while we continued to work like crazy. Luckily the publisher, realising that the ghost writer was weeks away from finishing, revised the deadline further, so we had until 12th July to finish our book. I sent a polite email to the publisher saying that in order to complete the ‘fleshing out’ I needed to know how much time to set aside. We wanted to know so that we could reach the target length and not have our version rejected for being too long or short. The reply gave us the information we needed and at 11pm on 11th July 2010 Tom and I concluded we had done enough for it to be considered finished: 80,000 words to be exact, even if the text was still a bit rough around the edges. I hadn’t had time to go through Tom’s half of the book properly which, while correct in detail, still needed the input of my emotional responses to situations.

Nonetheless, nerves at near breaking point, we wrote an email together describing what I had done. Tom didn’t want to give them any excuses to back out, and insisted that we didn’t specify his involvement in writing and editing in case they used the fact against us. I simply said that my reason for doing it was that it needed to be a book I would be proud to have my name on if I was to promote it. We attached our book and sent it to both the publisher and the ghost writer. Their emailed responses were understandably bitter:

“What a shame that you couldn’t mention this to (the ghost writer) and I as we have both been working so hard and the writing is so good. And he and I both emailed you quite a bit in the last few days, even today. It would have been helpful to know this was your approach and I reassured you even today about the deadline.”

It was true that they had both emailed me, but my nerves couldn’t stand reading them and, frankly, there wasn’t time. My confidence was at an all-time low, having been consistently lied to over the previous weeks, not to mention patronised and bombarded with insincere flattery. I had been made to feel as though I was a trouble maker, incapable of understanding simple concepts and, worst of all, that my problems with the project were of my own making due to my lack of mental stability. I felt betrayed by the ghost writer and the publisher, who talked incessantly about ‘real people with real stories’ but, it seemed, would stop at nothing to twist the truth of those ‘real stories’ and manipulate the ‘real people’. It was no wonder I hadn’t confided in them at that late stage. How could I when I knew exactly what their response would be?

The ghost writer’s reply summed up his attitude and viewpoint:

“I’m disappointed you weren’t willing to work with me on the writing of your book. I thought we were off to a good start.

“I spent many hours sorting through everything you told me during our work together, trying to understand your story from beginning to end. I’m sorry you thought I wasn’t working quickly enough, but I really did believe my method would save us time on the back end. I was trying to make a structure for the book I thought everyone would be happy with. As I said many times over, I was hoping you would go through the scenes I wrote and fix them to match your reality. Instead I gather you didn’t even read them.

“Oh, well. As I’ve tried to reassure you from the beginning, this has always been your book and not mine. If you’re happy then I am.

“As René Descartes said, ‘Souvent une fausse joie vaut mieux qu’une tristesse dont la cause est vraie.’

“Good luck.”

As with all his correspondences, he missed the point. He made out I was impatient and yet ten days after the original deadline had passed, only 34,000 words had been sent to me, when the target was around 77,000 words. When he stated “You weren’t willing to work with me,” he conveniently forgot the fact that he had ignored all of my requests for a plan or sample from the latter half of the book and only answered the emails that suited him. ‘Work with me’ effectively meant ‘do it my way’. As for consistently saying ‘it’s your book’, well…

Actually, I did read the ghost writer’s scenes and, to use the publisher’s vernacular, I found them ‘staggeringly’ bad! That might just be my opinion but if it was indeed supposed to be my book, then steamrollering over my opinion was a strange way to proceed!

The publisher said she’d get back to me with her thoughts about my book, which was actually rather more than I’d expected! Indeed, it was more than I got too, and she merely passed me on to a new editor. I took this to mean she couldn’t find any reason not to use it, especially as there was no alternative book to publish. We had won the battle and they had given in. At least that’s how it seemed. LR/PP