In Part 1, Dave Guttridge explained how he became interested in gramophones, talked about his musical influences and discussed the pros and cons of shellac 78s and vintage portable gramophones. In Part 2, Dave explains why some people are now recording onto wax cylinders, why he decided to do his own radio show and what The Shellac Collective is all about.

Dave as DJ78

DJ78 Premiere

Although Dave had played bass in many bands before starting his work as DJ78, he had never tried DJing. Nevertheless, the prospect of performing solo rather than as a part of a band didn’t overly bother him.

“I always thought that DJing looked fun and easy and, frankly, it is easy,” Dave insists. “It is not a hard job to put one piece of music on after another; the skill is in knowing what song will work well after the last song that you played.

“But I really appreciate someone like DJ Yoda who is a really skilful technical DJ. I saw his show at Camp Bestival in Dorset a couple of months ago. Instead of working from music on record, he worked from music videos and videos taped from TV, so the whole thing was based on visuals but with a heavy musical element. It was hilarious; he’s got such a good sense of humour. There is also a DJ called Mr Scruff who is another guy who really appreciates that old music that you find on Shellac. It often works really well in a new context so he’ll sample little bits of old 78s and drop them into his set.

“I think it was six years ago I made my debut at the Norwich Fringe, performing at the old Bally Shoe Factory on Hall Road, which we used as a sort of base for the Fringe. I set the decks up in the entrance, played records and got an immediate reaction. It just started to take off from there as people found out what I was doing. I set up a Myspace site then people in London started to call and I began going there with the gramophones.

“At first I wasn’t amplifying them at all; I would just do gigs acoustically. They are loud enough if you stand in front of them, but I realised, after doing a few, that the sound is very focused. For example, people on the other side of the room weren’t really hearing anything at all. So I decided to start amplifying them and for that I bought a small portable PA system and went down the simplest of routes, which is to drop a vocal microphone into the mouth of the internal horn of each of them. I just use a straightforward live vocal mic like a Shure SM58, because they are designed to cope with peaks. I quite literally drop those inside and pack them with a piece of foam so they don’t rattle around.

“Once the mic has gone in, I stuff the rest of the hole with black velvet so it acts as a sound baffle and takes the edge off. The sound is piercing when you are standing right next to them and I’m standing over them all the time. I used to come home with a terrible headache after doing two hour sets. The velvet has no effect on the output from the mics, as they sit further down in the horn, but it cuts the volume where I stand when working. Of course, stuffing the sound hole is the only form of volume control for the unamplified gramophones. Some traditionalists use a sock, which I believe is where the term ‘Put a sock in it’ comes from!

“I have used the gramophones completely unamplified on many occasions but, as I say, the area of projection is quite small, so these tend to be more intimate gatherings. My first appearance in London was at the Tricycle Theatre for an event called Naked Nights, which featured completely acoustic performances by groups and singers including Kathryn Williams and The Broken Family Band, using no electricity, not even batteries. I amplify the decks at larger outdoor events such as festivals and in venues like Spiegeltent and Shepherds Bush Empire.”

Dave’s DJ78 performances are not just about music; presentation is also an important part of the show. His usual uniform includes a vintage dinner suit and bow tie. The gramophones themselves, of course, look suitably vintage, but they are also interesting objects which benefit, aesthetically speaking, from plenty of shiny chrome-plated metalwork.

“Everyone says they look so beautiful,” insists Dave, “but you’ve got to bear in mind that they spend 90 percent of the time closed and the elements don’t get to them. When you open them the chrome work looks fantastic because it’s just never degraded.”

Winding the handle

The Shellac Collective

Aside from his solo work, Dave is also involved in a group called The Shellac Collective, which he co-founded with a friend and record dealer called Greg Butler. As its name suggests, the group is made up of like-minded shellac enthusiasts, who are equally interested in performing with old 78s. Dave explains how the group came into existence.

“After I had been doing DJ78 for a year or so, through Myspace I got in contact with Greg Butler who has dealt in second-hand records – specifically 78s – for many years. I was really pleased when I met him because one of the inspirations for doing what I am doing is John Peel. John would specifically play a 78rpm disk every night on the section of his show called ‘The Pig’s Big 78’. His wife, Sheila, was nicknamed the Pig, and she would choose the record. Well, it turned out that Peel was getting his 78s from Greg.

“Greg lives in Foxton just outside Cambridge and his house is literally full, floor to ceiling, with 78s. Every shed and outhouse is stacked with records, all carefully filed in the right place so that you can find what you are looking for. He has 100,000 plus 78s and everything is for sale. Twice a year he has an open day where collectors can turn up and rifle through everything. It’s a great meeting point for shellac enthusiasts and it was on one of these days that Greg and I said we should be doing something with all these records. We thought we should be going out together and DJing so we put the feelers out and found other people who were interested in DJing with 78s.

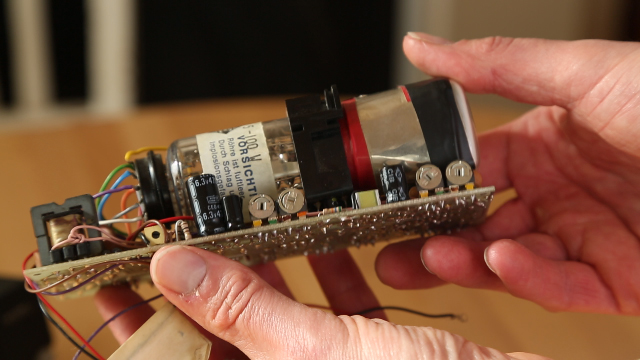

“Some of the people we found were already doing something similar. There is a group of girls in London called the Shellac Sisters, who were doing a similar thing, although they use adapted wind-up gramophones with magnetic cartridges fitted to the soundboxes so that they actually have a line out signal which is fed to an amplifier. So they are bypassing the acoustic horn side of it and going to straight to something they can amplify.

“We also discovered other collectors who wanted to DJ but didn’t necessarily already do it with gramophones and it progressed from there. There are now, I’d say, about 20 of us in the collective. And our big days out are things like Bestival on the Isle of Wight, where we have a whole tent which we curate. Everyone in the Shellac collective turns up and does their sets with their own records, but we have live music in between the shellac sets.

“We often, by necessity, have to use electric decks, just because amplifying the wind-up gramophones still doesn’t give you tonally, or sonically, the kind of sound that people want to dance to. All the tone coming off a wind-up gramophone is top and middle. There’s no bass so it is quite piercing and there is not really any way you can EQ it out. Yet the bass is actually enormous on many 1950s tunes. ‘Crazy’ by Patsy Cline, for example, has one of the best bass sounds you’ll ever hear recorded. If you get a good 78 of it and play it on a good deck it blows your socks off!

“So when we do big festivals we actually use this old disco unit with a pair of 1960s DSR decks in it – ‘the Wheels of Wood’ as they are affectionately termed – which are then amplified through a big PA.

“We’ve been in contact with a company called The Expert Stylus and Cartridge Company in Surrey and they have made new diamond conical styli for our decks. These diamonds are made to very, very precise sizes. There is a larger size which is for pre 1939 pressings, then after 1939 the size of the groove changed very slightly but perceptibly, so we use smaller styli to play later tracks. The custom-made styli fit into standard 1960s flip-over style cartridges. The diamonds should last for many years because they track at a very low weight of about 2.5 grams, whereas the steel needles, by contrast, take about 4 ounces! Vinyl wouldn’t stand being played with a steel needle, for example, it would be ripped apart, so vinyl 78s we play on our electric decks.

“Using steel needles is basically like using a sledgehammer to crack a walnut: if you stick a steel needle in not much is going to get past it, but if you want to get to where the sound is best on the record you need to have a very precisely sized stylus, mainly because the groove will be worn in a certain place on a record where it has been played with steel needles. If you can then get the stylus to drop past that and into the bit that isn’t worn, but not so far that it drops into the bottom of the groove where all the dirt and debris collects, then you have the best possible sound from the record.

“We are talking microns rather than millimetres. There are companies that sell a box with six different size styli inside and the manufacturer’s advice is that the best one to use is the one that sounds best, so you try all sizes on a record. They are really for people who are making transcriptions of rare records. It’s complicated but I love tinkering to try and find the best needle for a particular record. It really appeals to me. It goes right back to my dad playing around with tape.

“We also wire all our cartridges to mono because no 78 is stereo. If you don’t do that and just play them with an ordinary cartridge, even though the music remains mono, the dirt and surface noise is picked up in stereo so you end up with stereo cracking but mono music! At least this way, by having them wired to mono, you get everything in the same plane.”

Attaching a steel needle to a soundbox

All in the Mix

A high level of surface noise is one of the main problems with shellac records, which Dave attributes to impurities in the shellac material itself. The old 78s were actually made from a compound material comprising shellac, carbon black and a bulking agent such as slate or clay powder. Dave explains a little more about the qualities of shellac records and how they have varied over the decades.

“Different eras of manufacturing have given us periods where shellac records sound fantastic, like in the mid ’20 and early ’30s, and other periods when they are sound poor. They go through a real dip in wartime, for example, because there was a huge shortage of shellac while all the reserves were being diverted. I don’t exactly know what they did with it but that’s where all the shellac went and consequently, wartime pressings are dreadful. Most of it just sounds like grit because the filler is usually just a really coarse material. They used whatever they could to bulk it out, which would probably have included crushed up old records along with the paper that went on the label.”

“But you also find that certain record labels always had really high quality products. Deutsche Grammophon, for example, prided themselves on the quality of their pressings. Although there isn’t much of a market for classical music on ’78, the one exception to that is usually German symphonic stuff. The quality is very good if the record is played on a really good transcription deck with proper diamond styli.

“And then there were other labels whose pressings were always pretty dreadful, like King Records in America. A lot of the African labels struggled to get good shellac too, but issues of quality continued into the vinyl era. Whenever you used to hear John Peel play a Jamaican reggae single, for example, he’d always apologise for the quality of the pressing. I remember buying albums by people in the ’70s and ’80s and if they were pressed in Portugal you knew you had got a duff one. Vinyl records seem to vary enormously. At home we have 7-inch singles that weigh as much as an album, but it seems quite arbitrary and the weight doesn’t affect the sound a huge amount.”

The horn from inside the HMV 102

Fashions and Formats

Ever since recording began, there has been debate about which format is the best. Improvements in audio quality may have been the most exciting developments for audio connoisseurs, but for most people, other issues such as cost, size and reliability are equally important. Today the MP3 format is king, replacing higher-quality formats (it killed off the high-quality SACD as a commercial replacement to standard CDs) and proving, if nothing else, that convenience and cost tend to outweigh quality in the eyes of the consumer.

But audio quality is only part of the story. Dave insists that the process of playing 78s, although relatively inconvenient and clumsy, makes people respond to music in a way that they wouldn’t if listening to an MP3 or a CD track.

“They have to respond differently because it is not just about the sound of the music – you get the visual aspect to it as well. The technology presents itself in such a way that people ask questions about it. Certainly the people who did not grow up with vinyl can’t work out how the music is happening; all they see is a black disk turning and they think, ‘Well, how does that work?’

“Children especially love coming over and looking at the gramophones and saying, ‘How does the music get from that black thing to what I am hearing?’ It’s quite a difficult thing to explain, but it is magical. You wouldn’t be asked to explain that process to a child who has an MP3 player, but with the gramophone you are showing the process in reverse, saying ‘What you hear actually comes from this machine and the sound was made in this way,’ and so on.

“Nowadays people have no connection with the music they are listening to at all and, as a consequence, it has been devalued. If you dislike something on first hearing it just goes out the window and you never think of it again. In contrast, in the old days you would put on a vinyl LP or cassette album and listen to it all the way through. If the track you disliked was in the middle, you’d hear it again and again until something clicked and you’d say, ‘Ah! I see what they are doing there now!’ You wouldn’t just put on the first couple of seconds of each track and go ‘Don’t like that or that,’ you would hear it all, see it playing and be affected by it as a whole piece. And every time you put that album on you’d get the same feeling because you knew what was coming next.

“These days we don’t give music that much time and it must be a nightmare for artists to decide on the best order for the tracks on their albums because people probably only download a couple of tracks.

“When I was at Greg’s house the other day we were talking about how every music format seems to halve in its life expectancy. 78s lasted from the First World War until the late ’50s. Then vinyl came in, which lasted from the late ’50s until to the early 80s. Then CD came along and everybody said, ‘It’s never going to get better than this,’ but CDs lasted maybe 15 or 20 years and have pretty much become redundant now. I didn’t like CDs because you lost all the 12-inch artwork, but I really dislike MP3s because they sound horrible and you don’t own anything physical.”

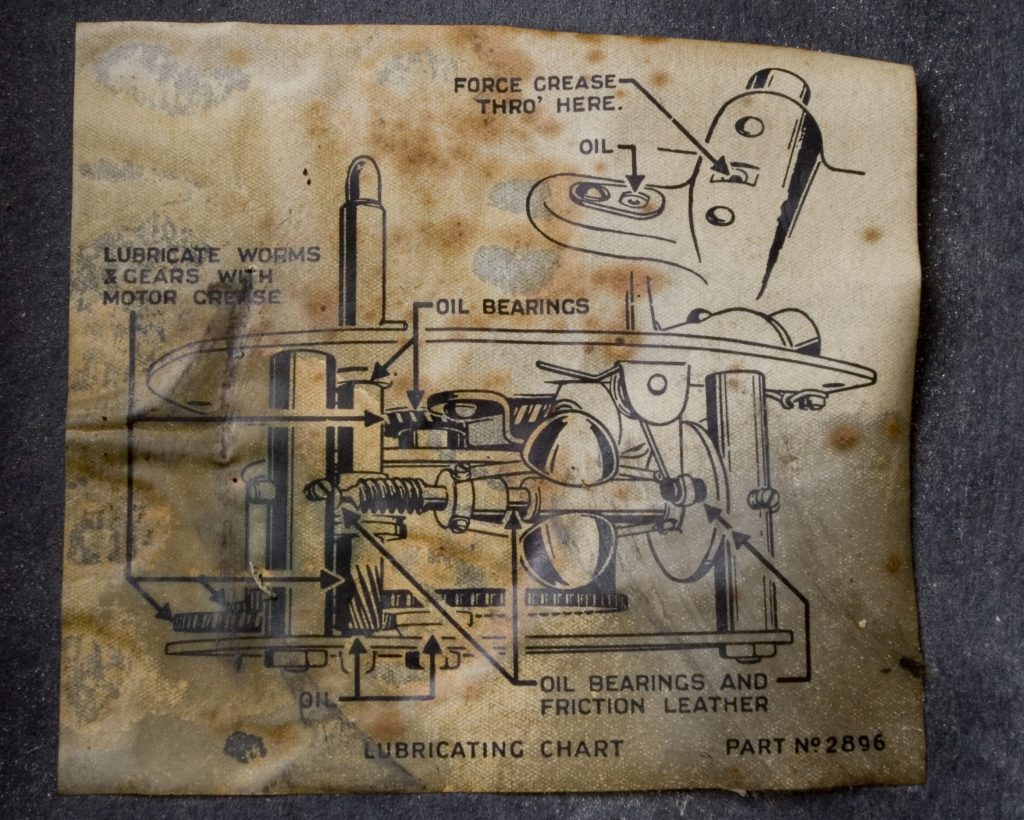

From inside the HMV 102 case, a diagram showing the moving parts which drive the turntable

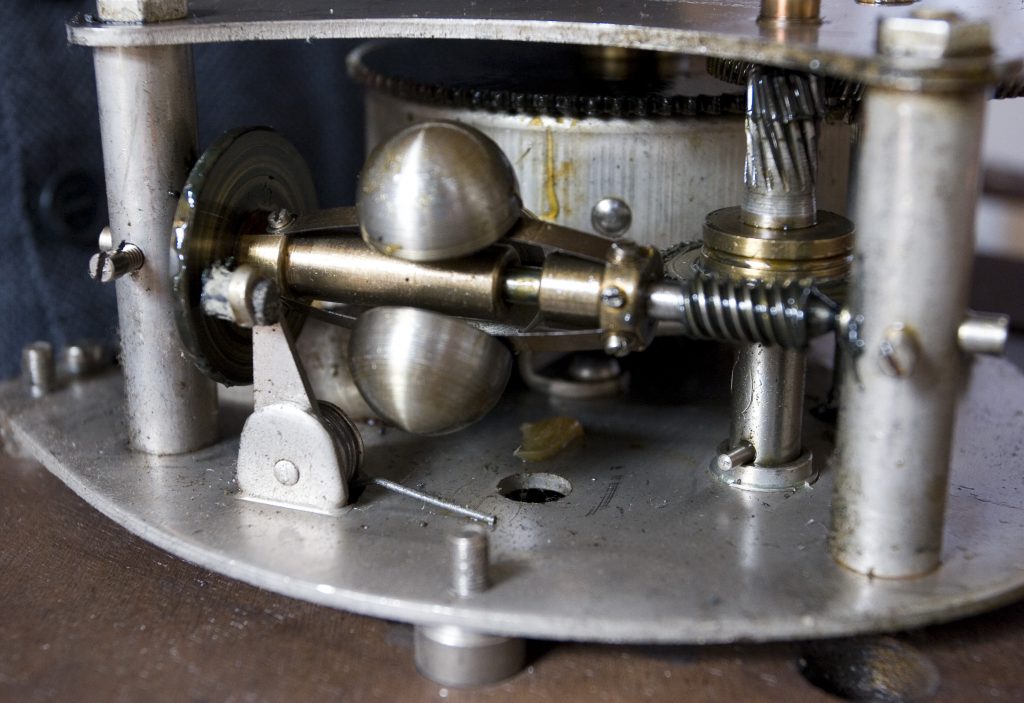

The mechanism within the gramophone. The spring housing is in the rear

Shellac – Too Modern, Give Us Wax!

Most of us know that advertising agencies and marketing folk make their living by denigrating the designs of yesterday while hugely exaggerating the life-changing properties of the new products they are trying to sell. This being the case, it seems likely that a hi-fi salesman would have few positive words to say about the qualities of gramophones and shellac 78s. Nevertheless, for some nostalgia fanatics, shellac 78s are still too modern and so they have revived the wax cylinder, first made popular in the 1880s by the likes of Thomas Edison! Such revivalism may seem crazy, but far from being an inferior format to the flat 78 disks, wax cylinders actually had certain advantages. In truth, their demise was more to do with equipment cost and storage convenience than quality. Dave explains some of the reason for the minor revival of wax.

“I think their resurgence is probably down to the influence of the steampunk movement. It’s basically punk music played by people wearing Victorian clothes with handlebar moustaches, and there is a whole movement that has grown up around this H.G. Wells-type aesthetic. The Polymath logo is actually what a Steam punk DJ kit would probably look like, because you would sit in a button-back leather sofa and you’d have lots of dials and pulleys and things. Steampunks just love anything with lots of plumbing and visible technology.

“There are now steampunk bands releasing music, and one or two of them thought that the idea thing for a Victorian-era band would be a wax cylinder record, so they have discovered a place which will manufacture 50 wax cylinders of a song. And they do a run of 50, get enough money to cover their costs and the cylinders become instant collector’s items.

“To play them you need an Edison Phonograph which is a box with a toilet roll shaped shaft that the cylinder fits on. You drop a diamond stylus onto the cylinder and the output comes through a horn. They are actually quite low wear because you are using a lovely diamond instead of the brutal steel needle that subsequent technologies used, but they do wear out eventually.

“Of course, the early records were one-offs. Someone would go into a recording studio, stand in front of a microphone, sing a song and that would be cut into the wax. That wax cylinder would then be taken off and another one would go on and they’d sing it over again. That was the way they reproduced a song. But they soon realized that it was folly to do that because the singer couldn’t manage more than about 10 performances before their voice went, so they had to work out a way of reproducing it.”

By 1901, methods of mass reproducing cylinders from a master recording had been invented, but, as history reveals, the familiar flat disk format of the 78, 33, and 45 rpm record won out in the end.

The speed adjust lever

Under the turntable is the first layer of mechanics. The horn and spring are below the sheet of wood

Shellac Radio

Dave’s DJ78 festival performances with the Shellac Collective allow him to reach a much wider audience than he able to when gigging with the HMV 102 decks, which are far better suited to small, intimate settings than the large stage. He has, however, found another way of performing that has the potential to reach even more people than his festival gigs – radio!

“It became obvious that one thing I should do was a radio show,” explains Dave, “where people from a wider area would be able to hear my records. Luckily the opportunity presented itself because the community radio station, Future Radio, started up in Norwich. They were very keen on the idea right from the start and have been really supportive. I’ve been doing my show for two and a half years now.

“The Sunday morning slot I have is perfect because the music of that era suits Sunday morning and just brings a smile to your face. I don’t usually do it live because I don’t like getting up early on a Sunday, so I record it. Then it gets compressed slightly for transmission, which seems to actually help reduce a little bit of the surface noise as well.

“I use a pair of Numark TT-1 turntables because they are one of the few turntables still made that will play 78s. The wonderfully satisfying thing about them is you have a 33 button and a 45 button and if you press them both together it adds up to 78! I always enjoy that. So I use those decks the studio with a basic 78 styli and cartridges and they sound great. The styli are a modern 78rpm needle and fit into standard Stanton 505 cartridges with the Technics-style headshells wired for mono output.

“The expensive diamond styli that the Expert Stylus Company made for us have been used by Greg on his ‘Kipper The Cat’ Radio show in Cambridge, but I’ve yet to invest in a pair for my show on Future. They are lovely but quite expensive. We are actually using those for transcribing 78s onto computers to be available for download from iTunes and other stores. We are talking to some guys in London at the moment about putting together compilations of 78s to make themed collections which will be available as MP3 downloads. It goes against my principles, but if it means that people get to listen to the music then that’s great. Otherwise people aren’t going to hear it unless they are lucky enough to come across us DJing somewhere.”

Dave and bass, many years ago

The Future of the Past

Dave’s DJ78 persona has proved to be very popular, not just in his home town, but nationally and internationally. He has been featured in national newspapers, and was even invited to Broadcasting house, together with his gramophones, to appear on BBC2s Working Lunch and speak about music reproduction formats. Dave tells of some of the offers coming his way, the limitations he faces and speculates on the future for DJ78.

“It is always hard to know where you are going to end up next. I’ve done gigs in places I’d have never imagined going to. I’ve just had emails from some guys in Madrid who are opening a club over there and one of the nights is going to be a regular 78rpm night. They’ve asked if I can go over and spin some records. But logistically I can’t fly anywhere now and have to go by train. That is because none of the airlines will allow me to take a box of records with me as hand luggage as it is too heavy, whereas before I used to get away with it on EasyJet and Ryanair.

“I have done gigs in the past where I’ve wrapped two gramophones in bubble wrap and loaded them into a large suitcase and that’s gone in the hold, while a box of records came on the plane with me as hand luggage and I simply wore all the clothes that I needed to for the gig during the journey. But I just can’t do that now.

“A trip to Belfast that I did a year or so ago, for example, was a 10 hour train journey up to Glasgow, then I travelled down to a ferry port where it was a six-hour crossing because the hydrofoil wasn’t working. All that effort was just to do one gig. It probably wasn’t economical, but it was a great adventure.

“The festival side of what I do is much better suited to people dancing, whereas playing with the gramophones works much better as an ambient kind of role. I do a lot of weddings because I’m the perfect background to an English garden wedding, after the service but before the meal, when people that are standing around with cocktails. The music just works so beautifully in that situation. I also do arts events and fashion shows, where people want something that has a very evocative sound.

“But nostalgia is a great thing and it shows no sense of dying off. There are more and more places that are running vintage nights and there are whole vintage festivals happening now. So I would have thought that the few shellac DJs that there are will never be short of work.” TF

Dave and two gramophones, taken September 2011 by TF

Part 1 of our interview with Dave be found here: Part 1

Dave can be contacted via his site: www.dj78.co.uk