Dave Guttridge is a DJ with a difference. His decks are a pair of wind-up gramophones and his records are mono shellac 78s from the days before vinyl. He explains how he fell in love with the bygone technology and discovered the wonderful qualities of old records.

Dave with his HMV 102, September 2011

“There’s always been this kind of hording instinct; not wanting to let anything go,” reflects Dave. “I’ve still got every piece of vinyl I’ve ever bought and every cassette I’ve ever recorded in boxes. I cannot bring myself to get rid of stuff.”

A Japanese minimalist might say that Dave Guttridge’s desire to hoard things is obsessive and unhealthy. That is certainly one point of view. Another might be that Dave, who trained at art school and has worked as a photographer for 25 years, has a love of beautiful objects and a deep respect for industrial design. It was Dave’s ability to see the value in a defunct format that set him on the road to becoming DJ78 – the UK’s first performing DJ using a pair of wind-up gramophone records and a batch of 78 shellac records dating back to the early part of the 20th century.

Dave’s fascination with gramophones and 78 records began when he and his wife were browsing shop windows and a HMV101 portable wind-up gramophone caught their attention.

“I think we were in Stratford when my wife and I, just on a whim, bought a gramophone,” Dave recalls. “We went past an antiques shop and saw this HMV 101. We didn’t have any gramophone records but we knew what it was and thought it would be great to play at home. We already had a 1960s duke box which we’d borrowed from a friend, which was great for parties and when people came round. People could press buttons to put on the records, which were seven-inch singles, but it had a really limited quantity of something like 40 records to choose from. We also had a reel-to-reel machine, a lot of vinyl and cassettes all over the place so the gramophone was just another format.

“When we bought the gramophone there were two records that happened to be with it. One was by Mario Lanza or possibly Caruso, and the other was a song called ‘Honey Hush/You’ve Been Reading My Mail’ by Fats Waller. We went back to the hotel we were staying at and put one of the records on and it just blew our ears off; it was so loud. Nothing prepared us for how loud these things were and we couldn’t play it in the room. You always think of them as providing little bits of background music in stately homes.”

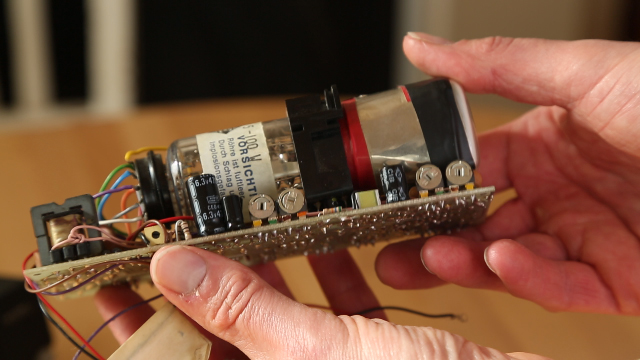

The designers of Dave’s HMV101 had found a way to amplify the sound picked up by the needle using the acoustic properties of a metal tube, probably taking inspiration from brass instruments like tubas. More impressively, they concealed the tube within the compact suitcase-style box of the gramophone along with all its other workings. Dave describes the innards of his HMV101.

“They have internal horns so the sound goes from the sound box through a long tube that gradually gets wider and ends with a big hole, which is the equivalent of the horn aperture on a horn gramophone. The clever thing about the picnic ones, as they are called, is that the lid of the gramophone case, when open, becomes a reflector and reflects the sound out.

“We just thought it was incredible so we started collecting gramophone records in a very small way. We’d take the gramophone round to friend’s houses in summer, sit outside and put a record on. Then one day my wife just said, ‘You know, if you had two gramophones there wouldn’t be a gap between the records and you’d be a DJ!’ We thought it was such a stupid idea but, at the same time, it was brilliant. As far as I knew, there was nobody else doing that, or no one that I’d heard of, so I bought another gramophone.”

HMV 102: the sound hole is stuffed with velvet – we talk about the reason for this later!

Different Sounds

The second gramophone Dave bought in order to create his DJ78 setup was a HMV 97D, but he soon discovered that it did not sound the same as his 101 and handled the playback of certain records quite differently, causing him to begin investigating what factors affected the sound.

“I didn’t twig, until a little bit later, that different models did different things,” he admits. “The HMV 97D sounded a bit harsh so it was donated to a local care home, together with a bunch of ’30s and ’40s shellacs. The HMV 101, on the other hand, was great for 1920s and 1930s music but it couldn’t handle late ’40s and 1950s records because they were pressed too loud.”

Dave discovered that the increased level on the later pressings were a problem because they were overloading the part of the gramophone which translates the vibrations of the needle into sound – the sound box. The 101, a machine, manufactured from the mid 1920s onwards, used a No.4 soundbox fitted with a mica diaphragm. Dave describes the overall assembly.

“The needle fits into the sound box and you can see the sound box just above where the needle sits. The No.4 soundbox diaphragm is made of mica which is a natural material but has been modelled to form a reddish plastic film. The needle’s movement makes the mica film vibrate which is then amplified by the gramophone’s internal horn.

“I realized that I wasn’t going to be able to play all the records I wanted to on the 101 so I went looking for other models and tried a few out. The model that HMV brought out after the 101 was the 102, in 1931. It had three different sound boxes available and I found one of those which could handle pretty much everything I threw at it, so that’s the only one I use now. So I use HMV 102s with 5A sound boxes. The 5As are now so collectable it has become an art finding them. One in good condition will set you back a couple of hundred quid.”

Although Dave knows of no one still manufacturing the 5A soundbox, it is a component which should last a long time, so a small stock has the potential to last its owner a lifetime.

“They last pretty much indefinitely unless they are really abused,” Dave insists, “but they can suffer from metal fatigue because they are all metal with, I think, an aluminium diaphragm. If you tap a bit of tin foil the foil amplifies that tap, and that is basically what the sound box does. I’ve now got seven gramophones and most of them have got 5A soundboxes so, fingers crossed, that will see me out. You just basically stock up on as many as you can find.”

The 5A sound box for the HMV 102. Dave found it a better all-round product than the HMV101 with a No.4 sound box

Getting the Needle

Gramophone needles are one of the most important of all the components in the playback system, for it is the needle which sits on the surface of the record and is responsible for translating the grooves into sound. As Dave explains, making sure the needle is regularly changed for a new one is absolutely essential.

“The needle is made of very poor quality steel and it is designed to wear out before the record. So the grooves in the shellac record wear the needle down from its really sharp point after one play.

“A lot of records I get given from old collections are unplayable because they were probably played with one needle for a long time. People used to put one needle in at the beginning of the year and then maybe change it at Christmas, and by that time it would be like a chisel, taking the surface off of the record.

“I always change the needle after every play. I play one side of a record and that needle is then thrown away. You get into a rhythm with it. While one record is playing you are changing the needle on the other gramophone, putting the new record on there, winding that one up, then you go back to the original one and wind it a bit more.

“While you wait for that one to finish and reach the last couple of bars of music, you hit the next one with the needle and just hope that it hasn’t got a long run in at the start. Of course, from knowing the music and by actually looking at the record, you can tell roughly when that record is going to finish, so you are just trying to get the needle on the other record so that there’s the minimum gap between the two pieces of music.”

It is obvious that Dave must get through a lot of needles, not only during his DJ performances, but also at home as he tests out each new record he buys. Fortunately, unlike the 5A sound boxes, needles are readily available and still in production.

“I’ve heard two stories,” says Dave. “One is it’s a couple of old gentlemen in a shed in Sheffield who turn them out. The other apocryphal tale I’ve heard is that there is a steel manufacturing company in Sheffield which closes down part of the line for half a day a year and transfer over to making gramophone needles, and in that half a day they make enough to supply the world’s demand.

“I buy them from a third party so they are probably made in China, but I like to think, and as far as I know, they are British made. I buy them in quantities of about 1000 a time, but they don’t take up much space and they are cheap. It costs about £4 for 100, so I don’t mind replacing them. But I just wish I could find a use for the dead ones because I’ve never thrown any of them away! I’ve got a big bag full of steel gramophone needles that are of no use to me.

“The HMV 102s can actually use a range of points but steel is the most common and comes in three volumes – soft, medium and loud. Tungsten tipped needles were introduced which were claimed to be good for approximately 50 plays and both thorn and wood needles were sometimes used. These produced no wear on the record, but resulted in a very much reduced volume and had to be sharpened with a special device after each play. Diamonds never entered the equation, probably due to the difficulty in mounting them, or perhaps because the enormous tracking weight of the soundboxes was a problem.”

Unlike modern portable music players, which run on batteries, the old gramophones were wind-up devices which used springs to store the energy needed to power the turntable for the length of a typical 78 record. Winding the gramophones is something Dave has to fit into his set between changing disks and needles, and has become an integral part of the DJ78 performance, adding to the overall spectacle.

“Once a player is fully wound it is supposed to do a whole record, but I wind them constantly because it is an insurance policy against them slowing down. They actually like it if you wind them while they are working!

“There is an enclosed spring underneath which gradually releases and turns the turntable, and there’s a regulator which allows you to adjust the speed a little bit. The regulator is basically an arrangement of spinning weights and you extend or suppress the amount that the weight spins out to change the speed of the turntable.

“Underneath they are beautiful pieces of equipment with absolutely stunning engineering, and they made millions of the things. And HMV never changed the design. They made the 102 model gramophone from about 1931 right through to the late 1950s without a single change to its design.”

Although Dave’s gramophones are incredibly well engineered bits of equipment, they still require maintenance and occasional repairs. One of the components which has a tendency to stop working or break is the aforementioned spring which becomes ever tighter as the gramophone handle is turned. Incredibly, like the steel needles, the springs for Dave’s old gramophone machines are still being manufactured somewhere!

“You can break a spring by over winding it,” Dave explains. “Otherwise they gradually deteriorate over the years because they are an enclosed metal box and the grease that’s inside solidifies. It’s not surprising when you think that the casing won’t have been open since the 1930s. When the grease becomes solid it stops the spring from opening smoothly. Luckily there is one guy who I know of in Bedford who runs a gramophone maintenance company and I’ve just got three gramophones back from him with new springs, fully serviced ready to go.

“I’d much prefer him to do that maintenance because the springs are very dangerous things. If you open a spring box it can have your hand off. They are basically just like a coiled Stanley knife – a really sharp edged piece of steel. So I let him do all that. But apart from that you can maintain them very easily because there are very few moving parts. They are mostly just a series of cogs. I’ve got ones working before and it is something I’ve always been quite pleased about because I have a love of pulling things apart and putting them back together again. I clean all the old grease off, put new grease on; tinker with a few screws and make sure everything is tight.

“Then they just keep going. There is absolutely no planned obsolescence about them; they were built to last more than a lifetime. HMV weren’t thinking ‘Well, if we build them to such a standard they will break after 10 years and people will have to buy another one,’ they didn’t think that way in those days.”

Old steel needles – used once

Various needles: note the half-tone, soft tone and loud tone boxes

They thought of everything in those days!

Musical Influences

It probably won’t come as a surprise to anyone who has read this far to learn that Dave is passionate about music. That passion can be traced right back to his childhood, and Dave is quick to credit his father as a major influence. Not only did he expose his son to a wide variety of music from an early age, he also dabbled in recording and tape editing, and it was these experimentations which encouraged Dave to think about the ways in which music can be captured and archived.

“I’ve just rediscovered my dad’s old Akai reel-to-reel,” says Dave. “He would make up compilations tapes on it and there would be everything on them from James Last to Mahler. He had a really nice record deck too, so I grew up being in awe of nice equipment in lovely wooden cabinets. He actually won this beautiful top-of-the-range Capitol record player when he lived in Cambridge. He’d named a compilation LP in a competition and amazingly won it together with a load of records. This would have been the top-of-the-range Bang & Olufsen deck of its day and he never bought another deck.

“He was a big Cine fan and would make Cine films and then adapt his record deck to run reel-to-reel quarter-inch tape around a big loop and make loops up to go with the film. He wouldn’t have known who Stockhausen was but he just loved getting his hands on the tape and literally cutting the Cine film and the reels of tape.

“So there’s always been music technology around me and it is something I still absolutely love with a passion. I grew up realizing that you didn’t just have to listen to music; you could do other things with it, all because dad did other things with it. Rather than just put the radio on he would record a radio show and then maybe chop out the bits he really liked.

“I remember we were watching a TV programme about Terry Gilliam – this was when Monty Python was still on TV – and Terry Gilliam said that he had recorded a Jimmy Young show for a week and chopped out every time Jimmy Young said his own name, and then Terry made a tape up by pasting every word together. It was crazy but my dad loved this idea.

“I remember playing around with the reel-to-reel and basically abusing it. Rather than record at a set speed, I would start to play around with the reels and get them to run at different speeds to find out what would happen if you recorded at one speed but played back at another, or chopped a bit of tape out and turned it around so that it played backwards for a bit.”

Eventually Dave started lugging his father’s reel-to-reel along to gigs and recording local bands, slowly building his extensive tape archive in the process.

“It’s not exactly portable,” laughs Dave, “so I used to talk to the sound guys at gigs and they would let me stand this reel-to-reel next to them, put two microphones on stands and record the gig! No big names, I have to say, but local bands. Or, if I hear that a band was rehearsing somewhere and they wanted to hear what they sounded like, I’d just turn up with my reel-to-reel.

“It was a similar thing to what Kingsley Harris does with the East Anglian Music Archive, but he has defining points for what he wants to do. He just works in East Anglia, whereas I would find tapes of weird stuff. I still have boxes and boxes of cassettes that I will probably never listen to again but can’t bear the thought of losing. Most of them are not things you would buy again on CD – they are one-off tapes of a gig.

“I’ve just leant my dad’s reel-to-reel to Kinsley Harris because he’s got a load of reel-to-reels of radio interviews that he is planning to transcribe, so he’s using it at the moment. After that I am going to work through my boxes of tapes from the ’70s and ’80s just to see what’s on them because there are bands who never officially recorded and I’ve got tapes of their rehearsals.

“One of my prize possessions is my tape of a gig my band did, supporting the Smiths at the The Gala Ballroom, on St. Stephens Street in Norwich. It was the first national tour The Smiths did, in ’83 I think. ‘Hand In Glove’ had come out but there had been no album and they were still trying to decide what the next single was going to be. They’d set off on this tour and I’d read a couple of reviews of them, heard them on John Peel’s show and recorded the Peel session that they did.

“Then I heard that my mate’s band was going to be the support so I rang up the venue and said ‘They are completely wrong. There is no way they should be supporting them. You want my band, my band are perfect!’ They just switched the bill, knocked one band off and put us on!”

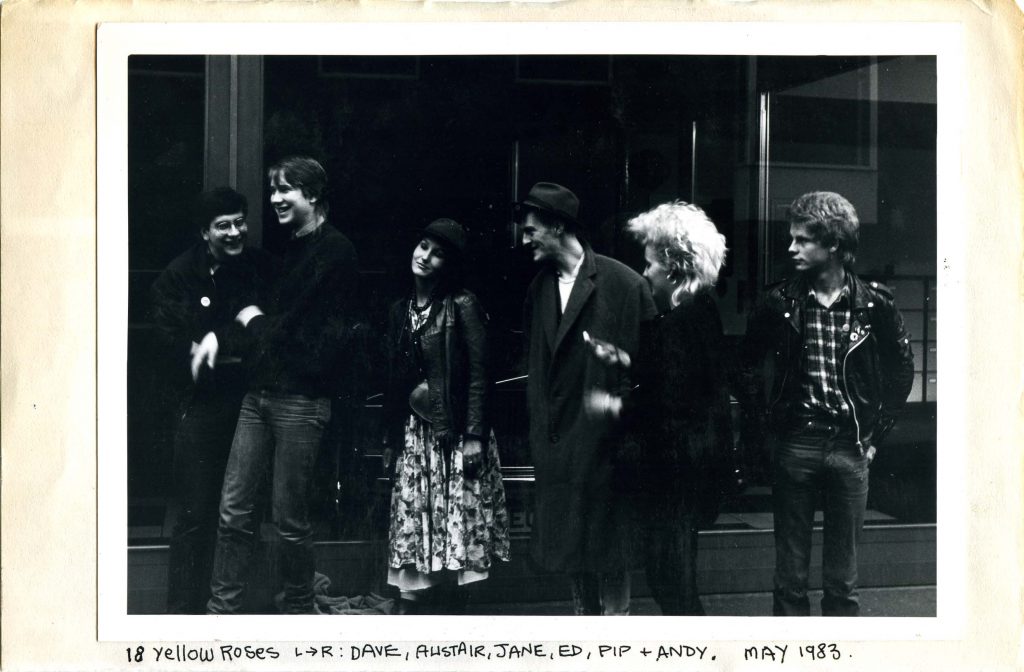

Dave insists that his friend wasn’t particularly upset at the time, although perhaps now, nearly 30 years later, he wishes he’d been on the bill with The Smiths. “They were a band called the Gothic Girls,” explains Dave, “so they would not really have been in keeping with The Smiths. We were called 18 Yellow Roses so we were perfect.

“But that’s a cassette recording and it’s one of the few cassettes I’ve actually taken the time to pull onto a computer and then make CDs for people, because it still sounds great. A friend of mine had bought a Panasonic stereo cassette recorder which was about the size of a big Walkman, had two little mics on the top and was considered almost semi-professional. At the time he was doing a cassette magazine of Norwich bands called Reel. When I saw this Panasonic recorder and thought ‘I’ve got to have one,’ and it ended up coming to every gig with me. I’d drive down to London to gigs and take this cassette recorder. I’ve still got it, of course!

“The mics on it were really good. They were condensing mics and they used to cope with an awful lot, which is why the Smiths recording sounds great. I was right in the middle of the crowd at the front, who were going mad, and there were people almost knocking the cassette recorder out of my hands because I wouldn’t put it down anywhere. I used to stand where the sound was best, which was usually right in the middle and at the front.”

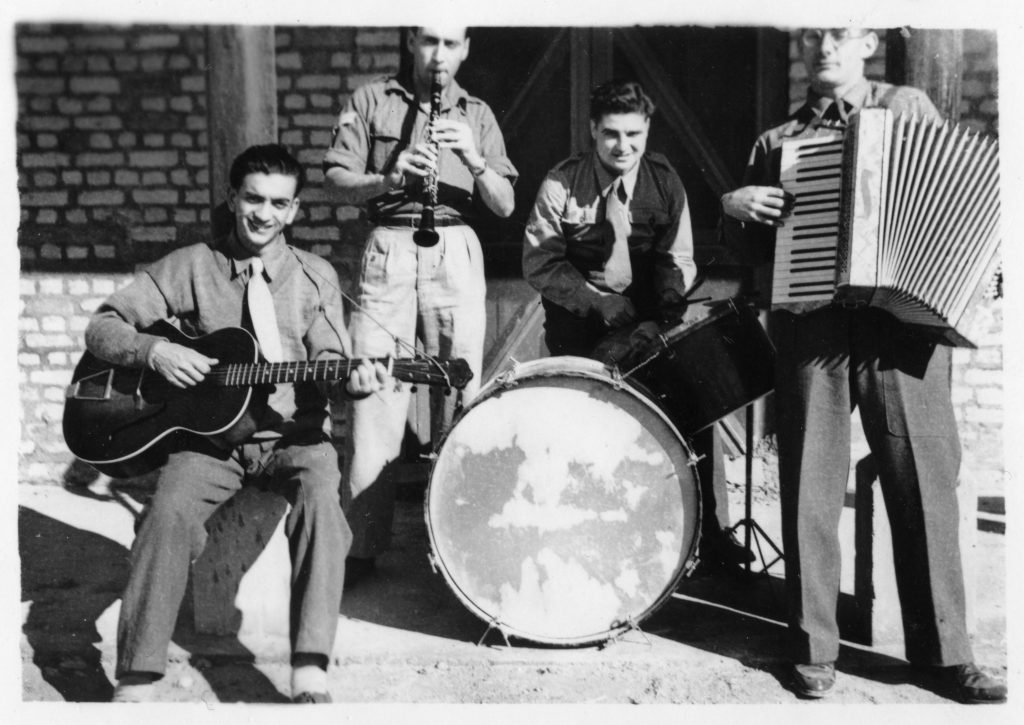

Dave’s inspirational father (far left) with his band in 1945

Learning To Play

Dave’s eclectic taste in music was also informed by his forward-thinking father, who introduced his son to a range of listening material and even performed as a musician himself.

“I grew up in a household where music wasn’t the predominant entertainment,” Dave recalls, “but it featured quite highly and luckily my dad had very catholic taste which he passed on to me. When he was in the army he started a band playing guitar and covering country and western, hillbilly stuff and a bit of jazz. Consequently he would never sit on one particular musical stool – he’d move around a lot and never restricted himself to what he listened to either.

“He loved classical music but he would still go out and buy a Lionel Hampton album and he loved Johnny Cash from the start. The last CD he listened to before he had a stroke was the last Johnny Cash album. We found that CD in the player. He never took the attitude that modern music is rubbish. He found good in everything which he passed on directly to me. And I grew up always wanting to be in a band.

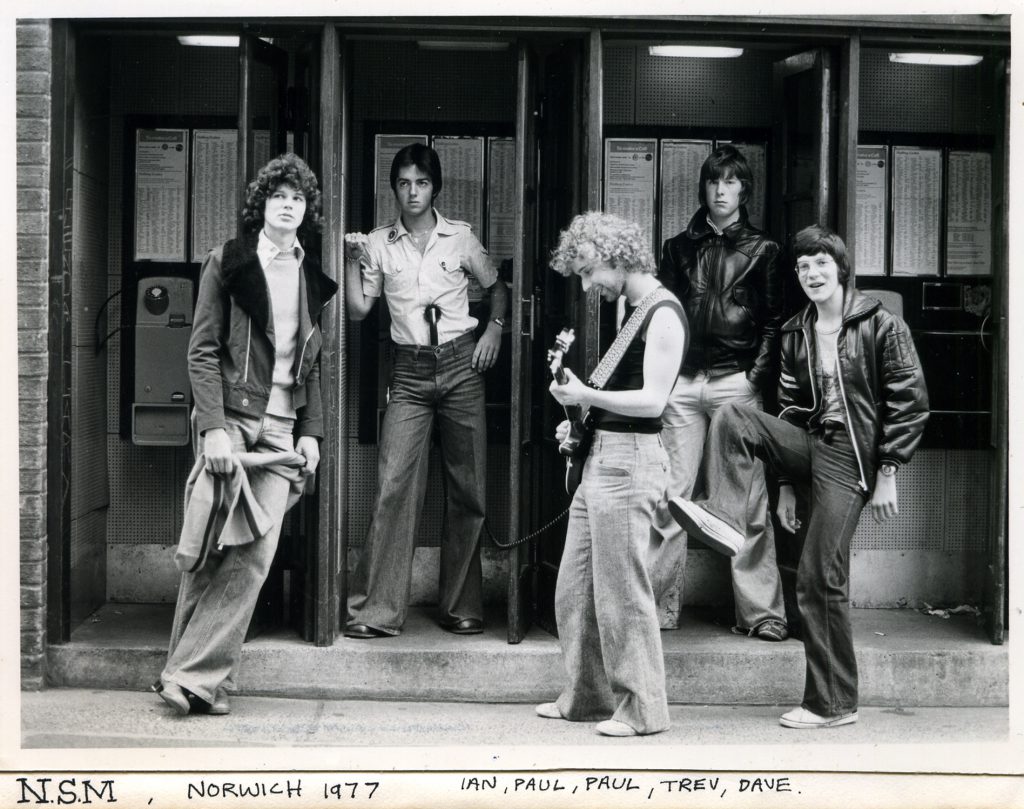

“So when I was 15 I bought my first guitar and bumped into a load of like-minded kids at school. We set about trying to organise a band but it was a nightmare. Today’s kids know what goes into being in a band when they are really young, but in those days we had an upright piano, a guitar with one amp, a microphone and a tambourine and we had to try and form a band with that setup!

“We were using the upright in the rehearsal room at school but we had no idea that you had to tune the guitar to the same tuning as the piano! We’d just head off in different directions and it probably sounded like some weird free jazz. But gradually I got working with people who knew how to put bands together and started playing in bands when I was 16, which has continued right until now.

“I started out on guitar but I was hopeless so I ended up playing bass because there were four strings and it was much easier – you didn’t have to learn chords. I rattled around in punk bands and had a band called The Stoats which used to rehearse in a bedroom at my parents house. We played all over the place and ended up being quite a popular local band. We never recorded anything apart from my reel-to-reels of the rehearsals.”

18 Yellow Roses: Dave’s band who supported The Smiths

NSM in 1977, looking more New Wave than 18 Yellow Roses

Not at all like the Beatles at EMI, honest!

The Stoats with Dave on the right!

Future of Shellac

Since the introduction of vinyl, records made of shellac have not been produced, and so there is a finite number of shellac 78s available. Nevertheless, Dave doesn’t seem to find that getting hold of them is a problem and now has a fairly large collection of his own. So large, in fact, that it seems unlikely he’ll run out of records to play any time soon.

“We’ve been collecting the records for about 15 to 18 years,” explains Dave. “But recently, as more and more people discover what I do, I’m constantly being offered collections of music which the owners don’t have a use for anymore. The records have usually sat in a trunk or box for maybe 20 or 30 years and, although they don’t haven’t a huge monetary value, if any at all, they do have a sentimental value and the owners just don’t want to throw them away. I am quite happy to give them a life and stop them ending up as landfill.

“Whenever I appear in local papers and on TV there is a flurry of interest from people who get in contact and offer me boxes of records. I’ve lost count now, but there’s got to be about 6,000 records kicking around. Of those, I probably only use a small percentage regularly, but it is still really nice to have them.”

“Their playability depends enormously on how they have been treated. Usually, even if they are in pretty poor shape, they can be played. But, generally, 50 to 60 percent of them are either things I have already got three or four copies of, or they will have been absolutely worn through by being abused in their working life.”

“If you play them with a fresh needle they shouldn’t wear out, but they do. Unfortunately the very nature of playing a gramophone record with a steel needle is destructive and it does take a little bit of the groove off every play. I’ve been doing this for six years now and I can no longer play a lot of records that I played at the beginning because they have literally worn out. Hence I am now trying to replace records that I still want to play from that original collection. Luckily there is still a thriving market with eBay.

“And there are still millions of shellac records out there because they don’t degrade over time. Even ones that have got damp or mould, you can just clean with some washing up liquid and a brush. Although they can break very easily if you are unlucky with them they are very hardy things. If you find one that is warped you can stick it under a couple of heavy books in a warm environment and it will go back to being flat!

“So they are still around, but it’s not entirely surprising when you think that it was the only way people could listen to music in the home for 60 years – it was the only music format.

“But at one time they were seen as worthless items and there was a phase when people melted them to make things like plant pots and lamp shades. They melt very easily! There is also a story that I heard from Barry Humphries who plays Dame Edna. When he moved to London from Australia, he was employed by EMI music and one of his first jobs was smashing 78s into a skip at the back of EMI house. This was because there was a crossover point in 1960 when EMI wanted people to stop buying 78s and buy the new-fangled and more expensive vinyl. So they destroyed the existing stocks so they couldn’t be sent out to the shops.”

Although no shellac records have been manufactured in any serious way for decades, the 78 format has not completely died out, and even looks to be making something of a come back, as musicians look at alternative ways to present their work.

“People are still pressing 78s using vinyl, and they sound fantastic,” says Dave. “If you think of the amount of information you can get into a groove on an 33rpm LP, you can increase that if you make a 12-inch single that runs at 45, and then again if you make a 10 inch that runs at 78. The amount of information that is being transferred as it runs is huge and the sound is fantastic, especially on vinyl where there is no surface noise.

“There is a three-piece rockabilly band in London called Kitty Daisy and Lewis who released their first two albums as a collection of five or six 78 vinyl disks, with one song on each side and a CD of the whole thing in the back as well. They are two sisters and a brother and are still very young, but Lewis, the brother, has grown up with his own cutting lathe in his shed and he cuts their records on that. But they sound fantastic – you can hear everything. He’s a master of recording and cutting and he uses a lot of old analogue gear. And these days you can get quite good high- quality vinyl to press onto.” TF

Dirty records need cleaning

In Part 2, Dave explains why some people are now recording onto wax cylinders, why he decided to do his own radio show and what The Shellac Collective is all about.

Part 2 of our interview with Dave be found here: Part 2