In Part 1 of our interview, Piers described how his interest in people led to a career in photography, working for music publications such as the Melody Maker throughout the 1990s. In Part 2 Piers talks about the equipment he uses, explaining his working methods and his views on the art of photographing people.

Michael Caine & Barbara Windsor, Museum of London, London Wall

27 May 2010

This is one of my favourite photographs of two British 60’s icons.

They may have moved in different circles but there is clearly a lot of fondness and mutual respect.

Branching Out

At least for a time during the early part of his career, Piers supplemented his photography with an income derived from various odd jobs he’d established over the years. By his own admission, he was living fairly comfortably compared to some of the younger journalists he was working alongside. “I wasn’t cherry picking jobs,” insists Piers, “I was taking jobs that were on offer to me, but I was travelling quite a lot and I had quite good equipment.

“I didn’t have any studio lights at that point. I may have had a tripod, but that was fairly useless in the job that I was doing and wasn’t required. But I had some early Canon equipment and my favourite Canon cameras were the T90s. I wasn’t using zoom lenses at the time so I had six or seven prime lenses, but I didn’t take particularly good care of them, I seem to remember. I was working in very rowdy environments at the gigs. Sometimes there wouldn’t be a pit at all and I’d get pushed around quite a lot, just because of the swaying of the crowd, the stage diving and so on.”

For a time, Piers got by using very little equipment and became confident to the point of complacency. Inevitably, he received an unwelcome wakeup call, when a job went horribly wrong.

“It took me a while to get the handle on things, really,” says Piers. “I should have been more experimental but I used to try using available light as much as I could and with an early commission I nearly blew it and could have lost my job.

“I remember going to Subterranea and photographing the Stereo MCs, in the autumn of 1989. I was feeling cocky and I thought I didn’t need to take my flash with me because there would be loads of available light. I didn’t know anything about the Stereo MCs, it was a small stage, a fairly wild audience, and there was no light. I just thought, ‘Oh my God, I’ve just completely fucked it!’ I remember there were only three frames out of about two rolls of film that were even vaguely printable. Luckily I survived the day, but I remember my live reviews editor saying to me, ‘You’ve really gone down in my estimation.’

“From there on in I played pretty safe having learnt not to take quite so many risks. I always made sure I had all the equipment that was necessary and always took more pictures than was necessary. Of course, you have to remember that this was pre-digital so there was no playback. Quite often it was guesswork about the exposures because the lights on stage were constantly changing. Sometimes I wouldn’t use flash and that would influence the pictures. Sometimes the spotlights would override what the camera was saying. I wasn’t fully manual so I was relying on a mixture of manual and auto settings.

“I didn’t make any further cock-ups until several years after joining Melody Maker when I was called up to Q Magazine and worked for them for a couple of years. I remember going to a Kylie Minogue gig to do a shoot for a particular page that I monopolized for a number of months.

“The venue put me miles away from the stage and I didn’t have a big lens. I think it was somewhere like Wembley Arena where normally you’d be put front-of-stage in the pit, but because there were pyrotechnics that night they decided to put all the photographers at the back of the venue. We are talking a great distance from where the action was happening. So I had to borrow a converter to stick on my camera.

“When I got home I developed the film, but just before I put it in the dryer I had a look at the reverse side of the negative, which was in a roll of 36, and to my horror, the image was really, really faint. For some reason the images hadn’t come out and at that point I remember feeling really quite ill.

“I thought, ‘I’ve really screwed up big time here,’ and to this day I am not entirely sure what happened. I think I must have put the camera on some kind of manual setting without realizing that the converter loses two stops of light. I think that’s what happened, but whatever the reason, it was a shocker.

“I can’t remember where Q Magazine was based in those days but I remember climbing three or four flights of stairs and taking a deep breathe before walking into the office. It felt like I was back in school wearing shorts, about to walk into the headmaster’s office. I was overcome with nausea, and I started sweating and tingling.

“I walked inside, held my hands up and said ‘I’m really sorry, but this is what’s happened.’ I told the truth. Luckily I’d already met another photographer who had been to the same gig and I asked him to supply pictures. He’s called Mick Hutson. Over the years he has worked for all the heavy metal magazines as well as Q Magazine and lots of record companies. Strangely enough, because he supplied pictures, that opened the door for him.”

Gilbert & George, at home in Fournier Street 2 February 1997

These two reminded me of a couple of Gerry Anderson puppets in perfect harmony. They moved and talked as one as though they were conceived in the same womb.

After the photo session was over I was asked to identify a pattern through a microscope. “What do you see” they chorused. Before

I could answer they said “stenguns!” Too embarrassed to disappoint them, I agreed.

Digital Days

Digital photography has made it possible for the photographer to see whether their shots have worked or not straight away, giving them a chance to make any necessary corrections on the spot. Nevertheless, there is still, unfortunately, enough scope for things to go wrong as Piers recently found out when he was forced to do a reshoot.

“There was one time about two years ago which was the first and only time that I reformatted the card without downloading the images, so I lost all the information. Luckily I was able to go back and do the job again and, because it was just a series of portraits in an office, it wasn’t a big deal in the end. I escaped pretty lightly!

“But I think the obvious positives of digital are that you can leave a job knowing that you have got what you need because of automatic playback. That’s very reassuring. There are other advantages as well. You don’t necessarily need a light meter and you don’t have to understand the relationship between shutter speeds and apertures. Very few people could walk into a dark room and decide what kind of exposure they were going to have, coupled with the shutter speed, so digital makes a big difference. Also, you don’t have to spend your own money to make money. In other words, you are not buying or processing film.

“When digital photography was just beginning, photographers used to charge clients a post-production fee for downloads, editing, CD burns – that kind of thing. But increasingly, as wages have stagnated and digital photography has taken hold, photographers are less inclined to charge for post production, unless it is actually proper Photoshop work.

“I use a program called Apple Aperture, for example. I import all the pictures into that piece of software and tweak every single image, correcting the colour temperature, contrast, exposure and sharpness, and cropping the final image. I shoot in raw mode so I can do the edits and convert to JPG afterwards. I do all these things to the image and don’t charge the client for that so they get a full package. That way I stay in business.

“There are photographers who do charge for those things, but they are probably few and far between, I would say. Before with film, although you had to find a lab, the beauty of it was that you’d hand over your films, go away for an hour-and-a-half or two hours, read a book somewhere then go back again and pick it up, and you wouldn’t have worked any harder! You might have kicked your heels around town, but it wouldn’t have been all hands to the deck and didn’t feel like work – you could indulge yourself for a couple of hours.

“I have to say, I am not a big fan of digital photography, particularly, even now. It feels too simple – it feels like cheating somehow. There are other reasons too. I not entirely happy with the condition of the pictures in terms of the way they look. My feeling is that film has a hidden depth – a kind of quality that digital isn’t necessarily capable of producing.

“Also, there is the instant gratification with digital photography that you don’t get with film. I remember the mounting expectation before dropping in on the lab, going over to the light box, slapping the transparencies down in strips and ogling each individual transparency with an eye glass. Those days are long gone but I miss that process in a funny kind of way.

“What I don’t miss, of course, is trekking to and from different offices with the hard copies – I don’t miss that – but I do enjoy emailing images; that’s the upside. It’s really quite satisfying knowing that they are no longer in my hands and are whizzing their way to their various destinations.”

Clearly digital technology has had a dramatic effect on the working lives of people in the photographic industry. Many have gone out of business, particularly those producing film-based products or developing them. Piers explains how his working day has changed over the years.

“It has changed quite a lot. There’s less footwork involved; less trips to buy film and chemicals – just less trips generally. Now you go to the place of work, take your pictures, come home, download, edit, and the image filing is simple. You just have to be careful not deleting anything, and there are various fail safes for that as well.

“I am lucky that I have only ever experienced possibly two corrupt memory cards. They don’t corrupt as much as they used to. I think the technology behind that has improved significantly. In the early days of digital photography there used to be a time lag between seeing what you were taking and what the camera grasped. It used to be as much as half a second sometimes. So you pressed the shutter button and actually didn’t get what you saw. That was during the infancy in the late ’90s very early 2000s when the technology simply wasn’t there.”

Piers Allardyce self portrait shot at home 17 March 2011

The Allardyce Kit List

Having been in the business for more than two decades, Piers has had plenty of time to refine his collection of camera equipment so that he has everything he needs, but not so much that he can’t easily carry it from one job to another. He talks through the various bits and bobs.

“I always have two of everything. A couple of years ago my flash gun exploded making a big bang and it stopped working. It frightened the hell out of me and I didn’t know what had happened. That had never happened before but fortunately I did have a backup with me.

“So, I have two flash guns, cameras, power packs and lots of cables. I always carry three different types of lenses with me. First there is the 70 to 200 which is a 2.8L series Lens which allows maximum light availability, so it’s top of the range, really. You can’t get better than the 2.8 70 to 200. I also carry a 16 to 35 and 24 to 70 which are also both L-series 2.8 lenses. So those are the three lenses I carry but I should probably carry backups for those too. The problem is that the more stuff you take with you, the greater the loss if something happens – either by theft or if something simply gets mislaid. So that’s very much in the back of my mind as well when I go out to work.

“Occasionally I feel vulnerable, depending on where I am going, but I never use metallic cases or anything that looks particularly photographic. I usually use a suitcase that you would put clothes in or a small carry-bag type with a handle, and these days I don’t actually use a rucksack at all.

“The price of lenses has been static for the best part of 10 years but a top lens cost between £1250 and £1300. They are actually a snip at the price, though, because the glass they use is very superior and a camera is only as good as the lens. You have to have good optics.

“I got into using the T90s pretty much from the beginning, and I stuck with those for a while. I’ve got about three Eos1N 35mm film cameras under my bed which replaced the T90. They have been gathering dust, but in addition to those I had three medium format cameras as well. I had a Rangefinder which was 6/7 inches. I still have a Mia RZ6/7 and a Contax 645. I used all three of those cameras in the latter years of Melody Maker just before it closed because the resolution of a 35mm camera just wasn’t good enough for a cover shoot really.

“But I have to confess that I was never happy using them, mainly because I was worried about soft focus. I haven’t mentioned that about six years ago I had eye laser surgery; I wish I’d had that earlier. I wore contact lenses from the age of 23 but the problem with contact lenses, particularly towards the end of the day, is that your eyes get tired and the lenses feel a bit greasy and sometimes they stick fast to your pupils because they become dry. And I could never be sure what I was focussing on terribly well. It was really tough with the Rangefinder because the error was much more extreme in terms of its focussing. You had to be really spot on with it’s depth of field. It had lots of different split screens you could use, where everything would come into alignment within the prism or viewfinder if you focussed, so that was quite helpful, but I would go through two or three because, although my eyesight was telling me one thing, my brain was telling me another and I had this terrible heave-ho with my imagination about what I was focussing on.

“These days I use a Canon EOS 1D Mark IV and a Canon EOS 5D Mark II.

“As for lights, I have four Bowens Esprit Digital 500DXs. They work in increments of a 10th of a stop, so they are very sophisticated lights. Once again, like my lenses, they are top-of-the-range. They are not the largest lights, but they are not the smallest either, and they are quite expensive. They are probably £430 each, and then you have to add things like the cables, the spill kills, and then of course you have to buy stands, a mixture of brollies, soft boxes, honeycombs and a light reflector.

“I also have a portable power pack as well for studio lighting, but unfortunately that has given up the ghost, so I am going to have to invest more money in that and they don’t come cheap. For two lights, or heads as they’re called, and a power pack you are looking at about at least £2500, I’d have thought. You have the ability to plug the power packs into the mains or you can just use them out and about on location without any power supply.”

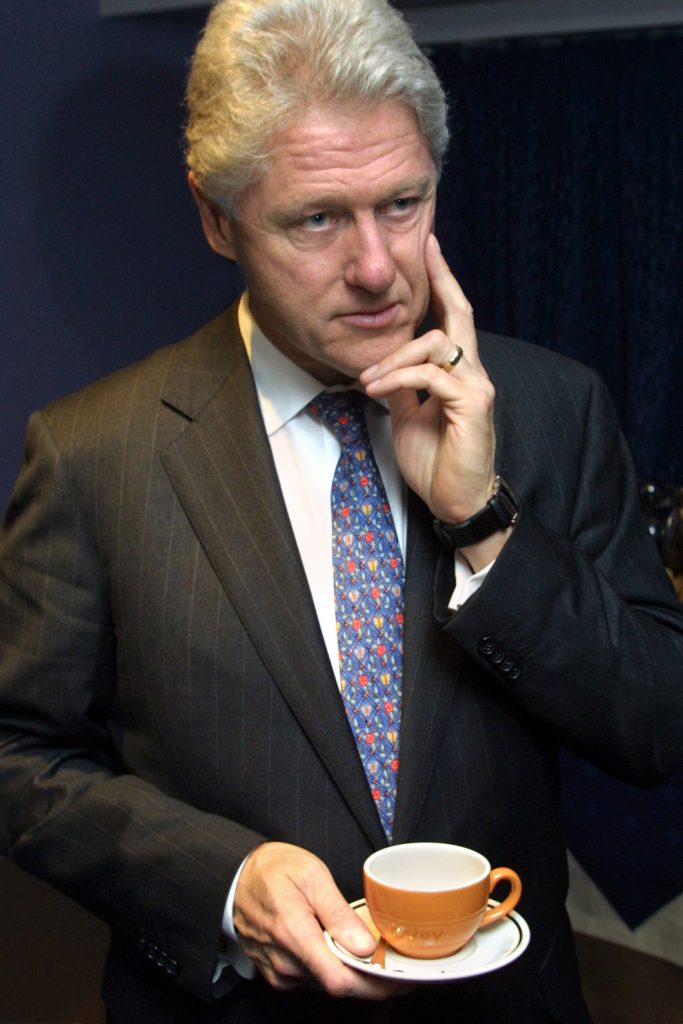

Bill Clinton 1 December 1999

Photos by Piers Allardyce 07976 724 390

Bill Clinton adddresses the Princess Diana Memorial Lecture on HIV?AIDS at the Queen Elizabeth Conference Centre.

This shot of Bill was not posed. He was deep in thought about the speech he would later make.

Less Is More?

When it comes to taking pictures, Piers is a strong believer in trying to get each shot right rather than clicking away and hoping to capture something good along the way. In his opinion, digital photography, where hundreds of images can be stored on a single card, has encouraged people to be more carefree with their shots, thereby shortening the life of their equipment.

“The other thing with digital technology,” explains Piers, “is that cameras and flash guns have to be much more robust because you shoot probably three or four times the number of images than you would normally with film. A lot of photographers take a very scattergun approach to taking pictures. I think it was Spike Milligan who famously said to a photographer, ‘Right, is that it, are we done?’ and the photographer said, ‘but I’ve only taken three frames!’ so Spike Milligan said, ‘well, that’s enough Silver, I’m off!’

“I do a lot of social diary photography which means I am quite often meeting other photographers at events and there is one photographer that I met on the circuit who takes hundreds of picture of maybe just a dozen individuals. I said to him, ‘Why do you take so many frames?’ and he said, ‘I can whip through them really quickly, I have this technique where I can see what’s going on.’ But I just think it is putting added stress and strain on the equipment. But he has a very kind of paparazzi approach to his work, so he’s waiting for something unforeseen to happen.

“So, photographers don’t necessarily wait for that decisive moment. What they sometimes do is treat still images like a film frames and rapidly fire off dozens of frames on the same subject. I’ve seen photographers take pictures again, again and again of the same subject and I’m thinking to myself, ‘That person’s expression hasn’t changed. You are just making more work for yourself with the edit.’

“It’s something I don’t understand because I think less is more. If I take a frame I always speak to my subject and say, ‘Each time I take a frame I want you to do something a bit different.’ I ask them to move their head, change their expression or body language, or perhaps change the location. I get people to stand up and then sit down again; move around the room and I check all the different vantage points and perspectives.

“That way you end up with something less filmic and more varied. That’s the discipline of shooting on film. But the thing about digital is that people think that just by pressing the button again and again they are achieving results, but they are ending up with the same result. And the problem with trigger-happy photography, particularly where things aren’t going to change dramatically, is that it shows a lack of nerve.”

Paul Tonkinson, Shot in Westminster 8 April 2008

Paul was heading up to Edinburgh for the fringe and needed a concept for a show about being comfortable with middle. I suggested

the seven stages of man. Paul said five would be plenty. I think it works very well.

Taking the Time

When an interviewer finishes questioning their interviewee they still have days of transcription and editing ahead of them when they get home. By contrast, when the photographer finishes the shoot and packs up they can focus on the next. It is therefore possible for photographers to earn relatively large sums of money if they can line up several jobs in a day, although they may not have time to take anything of value from the experience. Piers has a view on what constitutes the right length of time to spend doing a job.

“Depending on the logistics, some photographers, particularly the ones who work for agencies, can probably get four or five jobs in a day,” say Piers. “In London I am talking about now. It’s hard work and of course that’s dependent on the amount of time spent on that particular job, the distance incurred – that kind of thing.

“I’m particularly conscientious; sometimes I’ll overstay my welcome to get what I need. I know now more or less when I’ve got the picture. It’s a combination of experience and instinct. It’s knowing that people aren’t particularly volatile and that things aren’t going to fundamentally change from one minute to the next.

“I think what’s really interesting about photography is time and space. Time is a big factor and all sorts of things happen within a particular time frame. You get to know how long something is going to take before the moment elapses and things change. It’s a bit like judging the direction of the wind, in a funny kind of way. If someone is being particularly extrovert then you take more pictures, because their facial expression will change more often whereas if you do a corporate job, you find that business people tend to maintain a very similar expression. They are also shyer of the camera and don’t particularly enjoy the experience so you want to make it as painless for them as possible.

“You will spend more time taking pictures of someone famous because they enjoy the experience and they are capable of more moods and expressions. I’ve found that especially true of comedians. I’ve photographed lots of comedians for their Edinburgh fringe shows, where I’ll do a studio shoot with them or go on location somewhere, and they are capable of a myriad of expressions, moods and aspects of behaviour. You can spend hours with them, run off hundreds of frames and they’ll all be different.”

Piers has been a photographer long enough to have formed some definite opinions on what personal qualities a photographer needs to have in order to make a success of their career. He identifies several as being on a par with one another.

“I would say patience is really important. Never become flustered, always be calm and show you are in control and that you know what you are doing. Also, being liked is very important. If people don’t like you they won’t trust you and if they don’t trust you they won’t want to work with you. It also has to be remembered that the chances are that your paths will cross again at some point, and so if you want an extra mile from them – something a little bit different and a bit more exclusive – you need them to like you.”

“You have to remember it is a very artificial situation, much like hosting the news or presenting a chat show, so you are putting on the smarm. I’ve often sat in on interviews where the interviewee is being really charming, then as soon as the tape stops running they revert to type, so it can work both ways. It’s harder to do the more spontaneous things because people tend to pose, unless you stay long into the evening when they start getting drunk.

“But I carry on the chat even if I have stopped taking pictures. That’s what I meant when I talked about wanting to leave a job having learnt something about the person I’ve photographed. That’s really important otherwise it is all a little bit meaningless. There is a tendency for people to hide behind the camera when they are working. It’s complicated because an extrovert is less likely to be a photographer, because photography requires someone who is meticulous, steadfast, and isn’t displaying their own personality to get what they want. But actually, what you need from a good photographer, I think, is someone who is extrovert and flamboyant but can also do the technical things. If you get a mixture of the two then you’ve got a winner.

“In conclusion to that, if you look at some fashion photographers, particularly the really famous ones, they are good fun to be around, because they are constantly chatting and putting people at their ease. Of course, they have an advantage because they are working with models who know what to do.

“Working quickly is essential, it really is. It is better all round for everybody, but particularly for your subject. You need to work quickly because they will grow tired and weary and possibly troublesome over time. Then you lose the spontaneity and that is everything in photography, because they need to be relaxed.

“It’s a good learning curve to step in front of the camera sometimes and understand the predicament in which you are putting your subject. Quite often I forget because I am behind the lens rather than in front of it. It is unnerving when a lens is trained on you and there is a mixture of emotions that go on. Self consciousness is one thing, obviously, where the person is thinking, ‘What do I look like, am I presenting the best side of myself, will I look handsome, will I look pretty? Should I be thoughtful, should I smile or not? So the subject feels a whole range of emotions, whereas for the photographer it is often largely mechanical, and that’s why they’ve got to have good interpersonal skills. I think that’s really important, and I do meet a lot of photographers who just don’t. They are nice photographers, but they are nervous themselves, half the time.” TF

Part 3 of our interview with Piers can be found here: Part 3

To return to Part 1, click here: Part 1